Soho Theatre Walthamstow

London E17

It’s hard to imagine – a little as you may be reluctant to think about your grandparents having sex – how much previous generations loved colour in their buildings. There’s a tendency, abetted by black-and-white photography and the greying of buildings with age, to see history as monochrome or sepia. Yet now-solemn monuments such as the Parthenon and gothic cathedrals were as gaudy as you like. So were theatres and homes and pubs. Because, why not? Why wouldn’t people want the spaces of their lives to dazzle?

So it is with the former Granada cinema in the east London suburb of Walthamstow, a 1930s escapist palace whose ornate Hispano-Moorish interior was once painted claret, deep orange, bubblegum pink and gold – a mashup of high and low art and of ancient motifs and modern techniques unified by the principle that form follows fantasy. And, as this was a commercial enterprise, that profit follows both. It is architectural greasepaint, a cheap box cleverly dressed with hints of Andalusía; an Alhambra in paint and plaster. “The masses come to the theatre tired out after hard work,” said Theodore Komisarjevsky, the designer of its interiors, “and the picture theatre supplies these folks with the flavour of romance for which they crave.”

This wonder has been battered and mistreated over the decades and completely removed from view for most of the past 20 years. Now, thanks to a collaboration between the London borough of Waltham Forest and the Soho theatre, it has been rescued and reanimated and will open to the public next month as a venue for comedy, cabaret, theatre and panto. To say it’s like discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun, as you enter it off the shopping street on which it stands, would be an exaggeration – there are some differences in the timescale involved and the wealth of the treasures inside – but there’s still magic in finding this lost world.

Related articles:

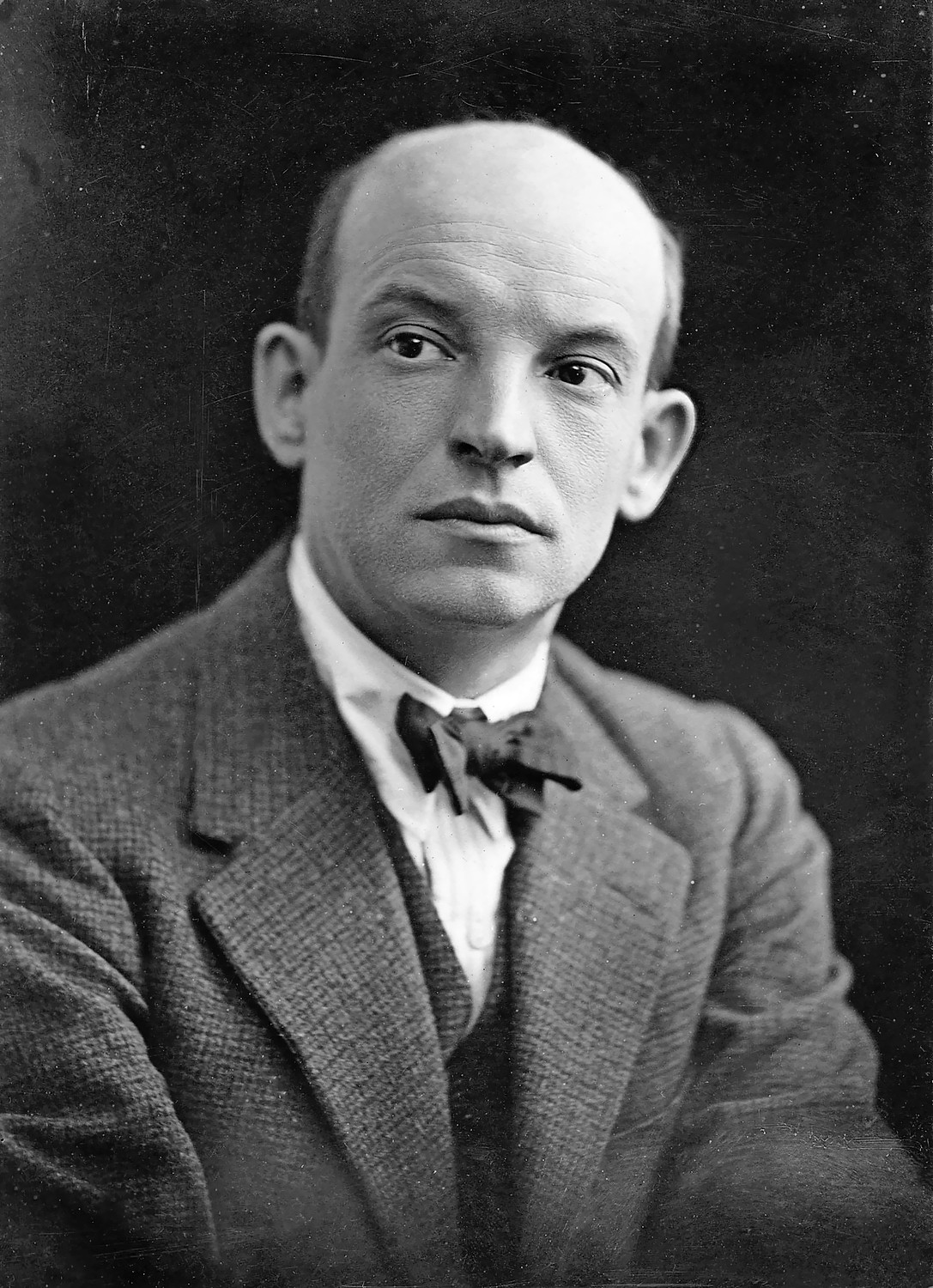

For Komisarjevsky, who was born in Venice to a theatrical Russian father and a Lithuanian princess, the design of some of the most memorable cinema interiors of the 20th century was almost a sideline. He was also a director, known for his groundbreaking productions of Chekhov and Shakespeare, the stagings of the latter accused by English critics of a cavalier approach to the sacred texts. The many romances of this short, bald but charismatic man included a brief marriage to the actor Peggy Ashcroft.

To say it’s like discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun would be an exaggeration, but there’s still magic in finding this lost world

He was invited by the young Sidney Bernstein (later founder of Granada Television and thus of Coronation Street) and Sidney’s brother Cecil to work with the architect Cecil Masey on cinemas they started building around 1930 – first in Dover, later in expanding suburbs and satellites such as Woolwich, Edmonton and Slough. Their most famous creation is the Granada in Tooting, south London, a 3,104-seat palace in a promiscuous gothic-Moorish-Renaissance-deco style that is now Grade I-listed. Walthamstow (listed Grade II*) was the second in the sequence after Dover and, until Tooting, the grandest.

Like many stars of the 1930s it fell into an up-and-down postwar existence. For a while, it hosted everything from pantomime to Dusty Springfield and the Rolling Stones, before being carved up into three smaller screens and closing in 2003. It was bought by the rich, powerful and controversial Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, whose plans to make it into a place of worship prompted a long and indefatigable local campaign to preserve it for entertainment, led by the McGuffin Film Society. “We were described as fantasists,” says the society’s founder, Bill Hodgson, but it persisted through “sheer bloody-mindedness. Residents felt the venue had been stolen from them, and people a little older knew what a special place it was. It was like going on holiday – such an escape from mundane every day life.”

The society won the support of Soho theatre, a company with origins in the 1960s, which for 25 years has been hosting work by the likes of Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Jack Thorne and Ryan Calais Cameron in its venue in Dean Street in central London, helped by the fact its chief executive, Mark Godfrey, lives in the Walthamstow area and picked up one of the campaign’s flyers at the tube station. The local council also began to back the rescue. Eventually, a public planning inquiry found against the change of use to a church. In 2019, the borough council bought the building, and in partnership with Soho theatre, who lease it at a peppercorn rent, started its renovation.

For Godfrey, the new theatre will, with 960 seats, occupy a middle-sized gap in the market between the 150 of their Dean Street base and the 3,655-seat Eventim Apollo in Hammersmith, west London. He believes that his company’s ability to spot and grow talent will help them draw audiences with the right acts for the venue. He wants the Walthamstow space to be “a local theatre with a national profile”, visited by people who can walk there from their homes and others from all over the country.

It is hoped to be, as it was in the beginning, a place of “glamour and fun”, of a “really good night out”, and “not a museum”. It will be well furnished with bars, including one at the back of the auditorium. It will also do such good and important things as providing step-free access, including backstage, and creating studios for use in education projects and by local community groups, among them screenings by the McGuffin Film Society.

The design of the renovation, budgeted at £30m in 2017 but now pushed higher by a number of factors, is by a team that includes the interior design consultant Jane Wheeler of JaneJaney Designs and the architect Fred Pilbrow. It aims to create an updated version of what Wheeler calls a “place of celebration and extravagance”. It’s not a reproduction of the 1930s version but based on “arrested decay”, which means drawing inspiration from all aspects of its past. (This is a concept of which the famous Walthamstow resident William Morris, who campaigned against the over-restoration of churches, might have approved, although one suspects he would have found the Granada’s flash impossibly vulgar.)

Ornamental plasterwork and timber have been, where necessary, reinstated and original chandeliers put back. The interior draws selectively on a palette loaded not only with the colours of the 1930s, but with the green and purple of its 1960s incarnation as a music venue, and the mint green and yellow of a brief life as Bollywood cinema. Some surfaces are left distressed and faded, some painted fresh and new. The foyer is pale pink and bright, charged with multicoloured details and a big mirror ball in the middle; the auditorium is more shadowy, its many hues combining into a purplish haze. New features – bars in conglomerate marble that looks like nougat, artwork printed on to mirrored wallpaper – add to the carnival spirit.

There are some necessary adjustments to its new life, proficiently done. The change from film to live performance requires a steeper rake to the ceiling, and the creation of a fly tower and dressing rooms. The current number of seats has come down from an original 2,700, achieved by giving more width and legroom to each, and converting the rears of the stalls and circle to bars. The front rows are undivided by aisles, such that performers will interact with solid walls of faces and bodies.

The Granada cinema’s character is fundamentally superficial, the work of theatre people more than architects. Its white, lightly ornamented exterior is secondary to the foyer and auditorium. As in a stage set, the surfaces are about achieving the most effect with the least means, an illusion conjured with the help of lighting. Seen up close, the decoration is nothing like the Islamic originals, their exquisitely carved marble here rendered in cruder and cheaper materials. Which is as it should be; it would be absurd if a place of entertainment were truly built like a palace or a temple. Now, in its latest incarnation, the building’s spirit will live on.

All photographs by David Levene