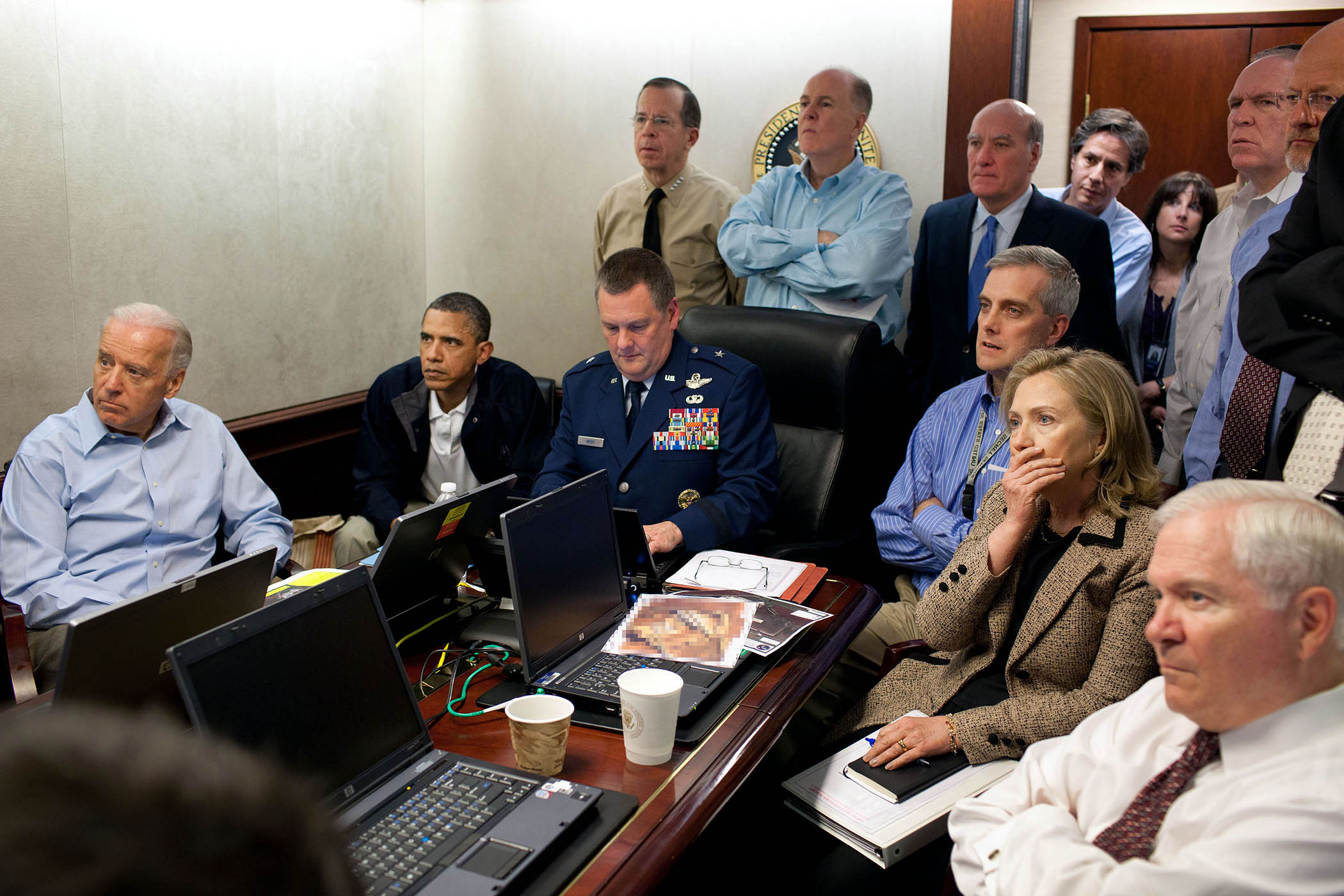

It is one of the defining images of the “war on terror”, taken in the White House situation room on 1 May 2011. As if preserved in aspic, it captures the stony expressions of President Barack Obama and his top national security team as they watch a live feed of Operation Neptune Spear, the killing of al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden at his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. All the key figures of the administration are crammed around the table, from homeland security adviser John Brennan to vice-president Joe Biden and secretary of defense Robert Gates. In the front row sits US secretary of state Hillary Clinton, with one hand on her notebook and the other covering her face.

Clinton later said the experience was “38 of the most intense minutes” of her life. Rather than gasping in shock, however, she claimed she was suppressing a cough from a summer allergy just when the photographer snapped. Within a few hours, once Bin Laden’s body had been identified, Obama strode confidently to the White House podium and read out a statement telling the American people that the mastermind of the 9/11 terrorist attacks had been killed. Just a few years before, when Clinton had been competing with Obama for the Democratic nomination, her campaign had produced a famous attack ad depicting her as the more experienced candidate on national security issues. When the 3am phone call came, announcing that the United States was under attack, who would the American people want to answer it?

The same 5,000 sq ft White House situation room has seen its fair share of action in recent months, as figures from the Trump administration have huddled round to watch the attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities last June, the bombing of radical Islamists in Nigeria at Christmas, the capture of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and the accosting of oil tankers in the Atlantic which opened the curtain on 2026.

How to make sense of the high-stakes nature of the decision-making at times of national security crises? And how to ensure the tactical and operational decisions taken in haste, and with high degrees of risk, service a higher strategic goal?

This is the task that Clinton and international relations scholar Keren Yarhi-Milo set out to explore in this edited collection, based on an academic course they have created together and teach at Columbia University, where the Yarhi-Milo is dean of the School of International and Public Affairs. In doing so, they not only offer their own thoughts but assemble a series of essays by distinguished scholars and former national security officials.

The contributors include former Obama administration figures such as CIA director Leon Panetta on the Bin Laden operation, Biden administration diplomat Victoria Nuland on the importance of public opinion, and Britain’s own Catherine Ashton, once the EU’s high representative, on the negotiations which led to the Iran nuclear deal. Lest it appear biased towards the perspective of those who share a Clinton-style worldview, the book includes an essay by Trump’s former adviser Robert C O’Brien, commenting on the operation that killed Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2019. It was this event, of course, that provided a memorable contrast between Obama’s carefully scripted announcement of the death of Bin Laden and Trump’s infamous statement that Baghdadi had “died like a dog”.

To an extent, Trump’s recent uses of American military power would seem to belie the idea that an academic method can be applied to make sense of national security operations. We are living in an era in which force is deployed more readily as a means of leverage and shaping geopolitical outcomes, rather than as a last resort in response to threats and crises. Nonetheless, there is always something that can be learned from the experience of others who have been in the room. This ranges from understanding the human pressures on those whose decisions involve risking the lives of others, to questions about “process” such as “Who do we need to talk to about this in advance?” and the all-important “What comes next?” It is the latter that’s going to bite at some point in the next few months with regards to post-Maduro Venezuela or Iran after the 12-day war of 2025.

We are living in an era in which force is deployed more readily as a means of leverage rather than as a last resort

We are living in an era in which force is deployed more readily as a means of leverage rather than as a last resort

Clinton and Yarhi-Milo are to be praised for attempting to bridge the gap between theory and practice, bringing in ideas from political science or social psychology such as prospect theory – which holds that we, as human beings, are instinctively more concerned about loss rather than tempted by gain. They are right to point out that deterrence theory – which governments are scrambling to relearn in this era of heightened tensions between nuclear-weapon states – depends, at its core, on calculations about the psychology of one’s adversary and indeed oneself. Some chapters speak well to our present moment. This includes discussions of why decision-makers are often inclined to use the “quiet option” (covert missions), and the balance between sticks and carrots that is necessary to make “coercive diplomacy” work.

Related articles:

Any such study in a British context would have to take more account of the long shadow that the Iraq war has cast over UK decision-making. The legacy of the conflict created anxiety over the political use of intelligence and the dangers of groupthink. It has led to a heavier emphasis on cabinet responsibility, parliamentary approval and fidelity to international law. Without doubt, these bureaucratic habits will come under increasing strain in a world where the pace of change is intensifying and our adversaries seek to benefit from the art of surprise.

There are many ways in which AI may be used to help with horizon scanning, threat assessment and expediting the clunkier elements of national security processes. But, by the time it reaches the centre of government, it will not replace the primacy of politics and the fundamentally unscientific nature of 50-50 judgments, or “gut” calls, taken in a swirl of external noise, strained internal group dynamics, and domestic and international pressure.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

As such, the one thing that feels missing in this book is arguably – at least from my own experience as someone who has traversed academia and government – the most important: the application of historical reasoning in the face of strategic challenges or critical decision points. Mention is made of the Cuban missile crisis, taught as a case study to generations of policymakers by Harvard professor Graham Allison. But one is left wanting more. Historians do not need advances in political science to expose the irrational nature of decision-making or the inadequacy of realist theories about international relations that hold that states will act in predetermined ways. Nor do they need systems theory to explain the failure to predict major events like the Iranian revolution or the fall of the Soviet Union. The best route to wisdom is historical understanding.

I am full square behind this attempt to bring down the walls between “the proverbial ivory tower and the halls of power”. But if I had only one book to recommend to an aspiring policymaker in this world of mad kings and banana republics, it would be a text from the 16th century: Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Inside the Situation Room: The Theory and Practice of Crisis Decision-Making, edited by Hillary Rodham Clinton & Keren Yarhi-Milo, is published by Oxford University Press (£22.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph of President Obama and his advisers in the White House’s situation room on 1 May 2011 by Getty Images