The timing of James Macintyre’s biography of Gordon Brown ensures that some paragraphs will cause sharp intakes of breath. For instance, this anecdote of the author’s from the Labour party conference of 2008 jumps out:

“I interviewed [Peter] Mandelson… and he told me he now backed Brown’s premiership, which was a surprise. I told Ed Miliband about Mandelson’s endorsement… and he reported it to Brown. The following week a rehabilitated Mandelson was elevated to the House of Lords and brought back to the cabinet as business secretary. In retrospect, the imaginative move – thanks to Mandelson’s skills, the surprise factor, and the fact that Mandelson was a Blairite who could quell criticism – nearly saved Brown’s premiership.”

Brown is obviously not to blame for Mandelson’s relationship with Jeffrey Epstein – or, indeed, for Mandelson’s disclosure of confidential government information to the convicted paedophile. Emails in the Epstein files show that Mandelson shared internal memos about the UK economy and even apparently gave advance notice of Brown’s resignation in 2010. (“Finally got him to go today,” reads one message on 10 May, the day before Brown stepped down as prime minister.)

Such leaks were clearly a betrayal of Brown, who has asked the cabinet secretary to investigate the disclosures. But this section of the book serves to remind us of the hold the “Prince of Darkness” had on New Labour and of how wilfully blind many of its senior politicians were to his obvious shortcomings.

Even Brown, who saw himself as the victim of Mandelson’s underhand dealing, was under the spell: “Mandelson’s appointment came after relations between him and Brown had slowly thawed during the first half of 2008… Brown, who still craved Mandelson’s undeniable skill and guidance, had followed up by making regular phone calls to Mandelson and also sending him speeches.” The book also reveals that, during this period, senior No 10 officials were tasked with wining and dining Mandelson.

The many Mandelson mentions in this interesting biography might be timely, but they underline what feels like one of the book’s weaknesses. It is as much – at times more so – an account of the New Labour project and the rupture with Tony Blair as it is a portrait of Gordon Brown himself.

The recounting of the simmering tensions with Blair take us down a well-trodden path. Even so, they remind us of one of the fascinating contradictions of Brown’s character. He is undeniably a conviction politician who wanted to use his position to do good – and in many ways, he achieved that aim. Yet he could not escape the feeling that he was cheated out of the Labour leadership by someone he had always seen as his junior. Brown’s resentment led him regularly to undermine and frustrate the cohesion of the government in which he was such a towering figure, as well as the vehicle for the change he wanted to create.

In the interviews the two men give, Blair is much more praiseworthy and gracious towards Brown than is the case in reverse

In the interviews the two men give, Blair is much more praiseworthy and gracious towards Brown than is the case in reverse

There is a naivety at play in the TB/GB psychodrama that is hard to reconcile with Brown’s intellect and political intelligence. The book drills down to the source of Brown’s belief that Blair reneged on the infamous Granita pact, made in the Islington restaurant in 1994. Brown believes Blair promised to step down after 10 years as Labour leader – in other words, 2004. Others believe that, if there was a commitment of this nature at all, it was for Blair to step down after two terms as prime minster which, assuming two full terms, would be 2007. As someone who spent a long time at the highest level of government, and who was once in a not-dissimilar position when I agreed to step aside from a leadership bid in favour of Alex Salmond, I am always incredulous that someone of Brown’s experience would genuinely think that a prime minister’s longevity in office should have been determined by a deal struck in opposition (assuming it was) rather than by events and circumstances in government and, more importantly, the interests of the country. However, the book leaves little doubt that this is exactly what he believed and expected.

Related articles:

In the interviews the two men have given to Macintyre, Blair is much more praiseworthy and gracious towards Brown than is the case in reverse. The sense the reader gets is that, for Brown, the hatchet is not, and might never be, completely buried.

Overall, though, this is an account from which Brown emerges well. For as long as I have been a member of the SNP, my party has always viewed him as something of an arch-nemesis. Our focus has been less on his strengths and achievements than on his political faults, chief among these his opposition to Scottish independence. It is clear from Macintyre’s account, though, that this has always sprung from the utilitarian belief that the union is a better route to social justice than independence – which I obviously strongly disagree with – than from any sentimental attachment to the symbols of Britishness.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Now, though, emerging from the trenches of frontline politics, I am able to view Brown more objectively. To my mind, Macintyre’s broadly favourable assessment of Brown is justified. It is also strengthened by being fair rather than fawning. For example, before concluding that his leadership in the aftermath of the financial crash was outstanding, the book notes a flaw: that the “light touch” regulation that he subjected UK banks to while chancellor (1997-2007) could “even be argued to have indirectly contributed to overly loose financial regulations globally, including in the US”.

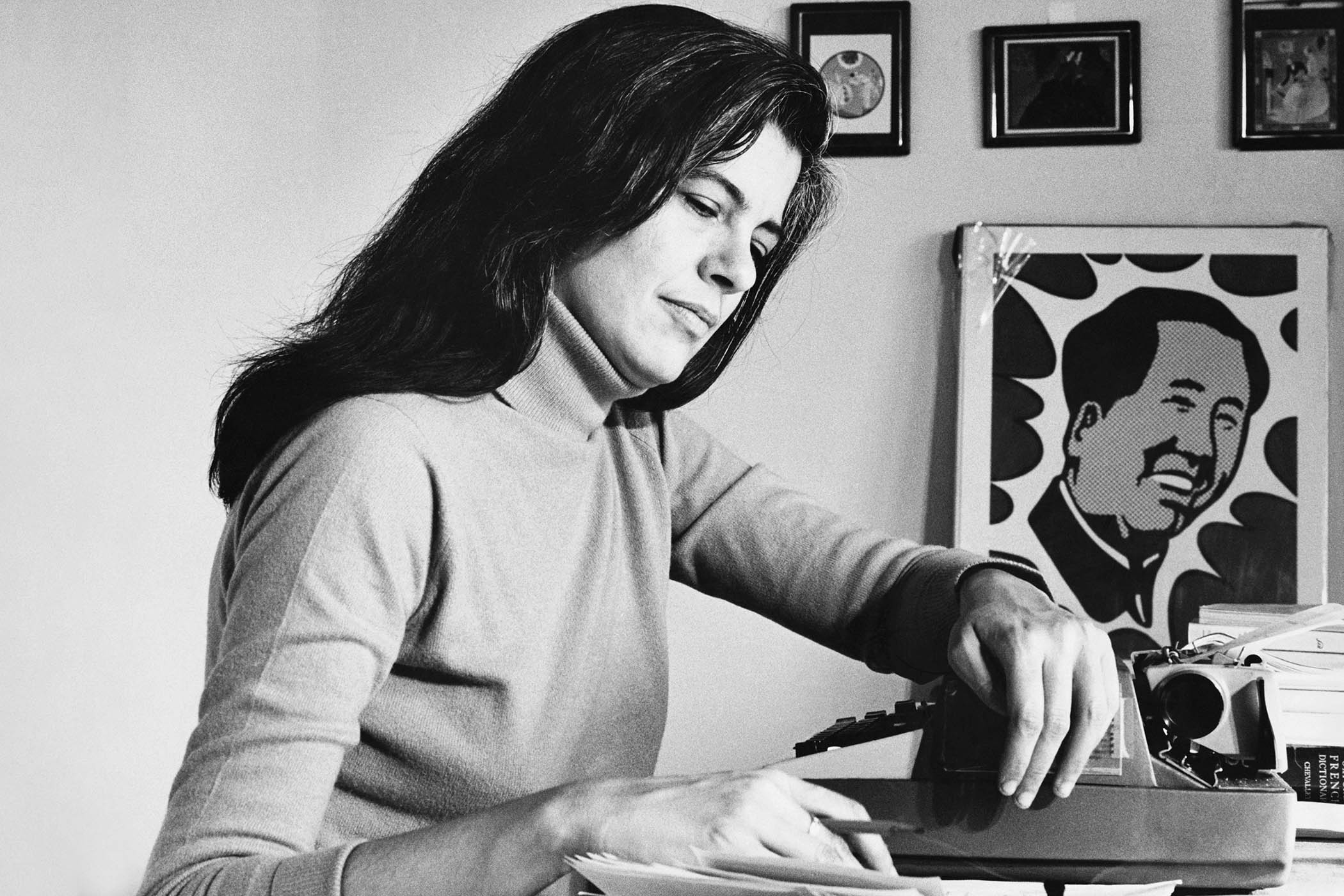

Prime minister Gordon Brown with his business secretary Peter Mandelson in 2009.

The opening and closing chapters of the book are its strongest. In the sections that come closest to adding to our understanding of Brown, we learn about the childhood influences that shaped the politician he became. Although he is almost 20 years my senior, I recognised many of Brown’s formative experiences in my own. Born in 1951, Brown grew up in Fife amid the unemployment and poverty of deindustrialisation which instilled in him – as it did in me – a lifelong commitment to advancing social justice. I think it is beyond question that his biggest achievement as a politician was the reduction in child poverty that happened during his time as chancellor. The closing sections of the book are also illuminating. As a man of faith – his father was a minister of the Church of Scotland – his views on the role of religion in politics are thoughtful and nuanced.

As Macintyre observes, perhaps one of Brown’s greatest legacies is in the example he has set since leaving office. Through his global work on education and his charitable efforts closer to home, he offers vital lessons on how to live a life of purpose in the post-leadership years.

For me, Gordon Brown has always been a political adversary. I have come to find, though, many more areas of agreement – for example on the means to best tackle poverty and the importance of the UK’s place in Europe – than I might hitherto have conceded. And there is no doubt that he is one of the most impactful and impressive politicians of our time.

This book is short on revelations and new insight: the reader will learn more about Brown in his own memoir than they will here. Nevertheless, it is a useful summary of who Gordon Brown is, what he stands for, and what he achieved. Above all, perhaps, it is an opportune reminder that our troubled world would be a better place if there were more leaders of his calibre, intellect and integrity holding positions of power today.

Gordon Brown: Power with Purpose by James Macintyre is published by Bloomsbury (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Andy Hall for The Observer, Christopher Furlong/Getty Images