Why does children’s literature matter? WH Auden pronounced, in the course of a long essay on Alice in Wonderland and Lewis Carroll: “There are good books that are only for adults, because their comprehension presupposes adult experiences, but there are no good books that are only for children.”

Exactly so. And what is it that these books that are significant for all ages have? I think that we who have written with equal application for adults and for children – and we are not that many – know that a children’s book is a particular endeavour. You are writing for a literary innocent, someone without preconceptions of what a story should be, how it should behave. So… let go and take off, shed your own assumptions about narrative.

There is indeed a change of register in writing for children, but you don’t write down to them, you write out of your own adult concerns and interests. You temper these, you tweak and adjust – Auden again – but adult experience takes a back seat here: you are back where you once were yourself, but endowed with the magical power of adult expression.

Book prizes generate interest in books. Not just a handful of winning books, but books in general. Hence it is great news that a new Booker prize for a children’s book is being launched. Children who read, and are read to, do better at school. Actually, I don’t care about them doing better at school, though others will. What I care about is the climate of the mind, the leap into suggestions of good and bad, of moral imperatives, of social possibilities, of other worlds.

My six-year-old great grandson has literary tastes that swerve from Vlad the Drac, a story about a young vampire written in the 1980s, to the Jumblies, who have been sailing the seas in their sieve since 1871. Children’s literature is not tethered to time: it floats free, whether written yesterday or a hundred years ago.

The author of an adult novel is of their time; the issues of the day tend to creep around the story – as do the attitudes and assumptions. We are writing now. We reflect our time and place. We need to.

The writer of a children’s book has license to abandon time and place, to create, to propose alternatives. It is an indulgence, and a hazard. The writer must find a language, a universe, that will persuade all – both the literary innocent that is the child and the sophisticated adult reader. And that is what the great children’s books have done.

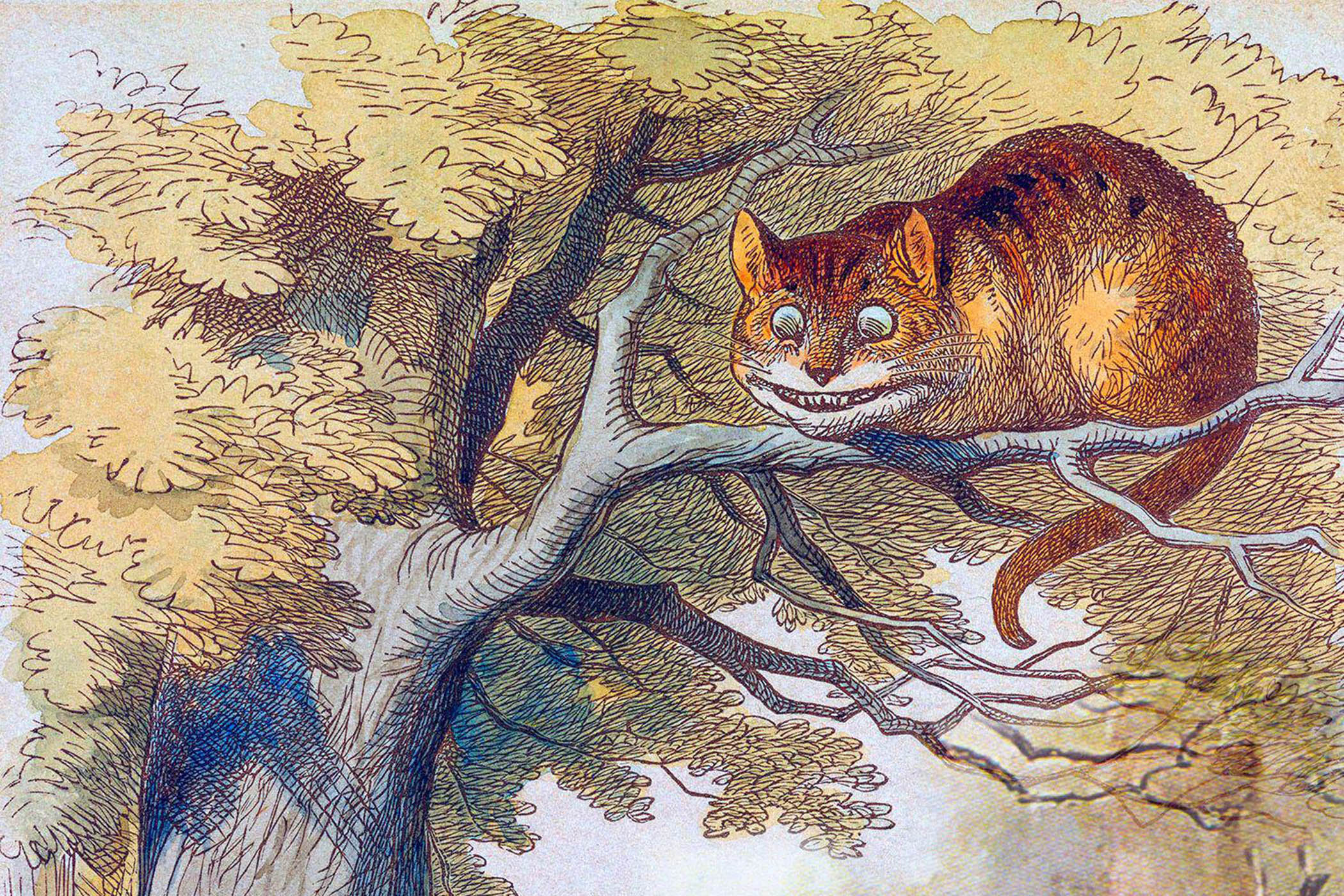

The perennials of children’s literature, the great books, are simply those that have become cultural landmarks, whose appeal is to all – children or adults – so that they have lodged in a million minds as an essential component of the imaginative furnishings. Auden was writing of Alice, perhaps the prime and original example of this phenomenon. Even those who have not properly read Carroll’s books will have some eerie familiarity with the Cheshire Cat, the Mock Turtle, Humpty Dumpty, Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

Related articles:

Author Penelope Lively photographed at home in London.

That was the beginning, and there was so much more to come. Kenneth Grahame’s Rat, Mole, Toad of Toad Hall; Edith Nesbit’s craft, as cunning with reality as with fantasy. And then the great age of writing for children in the mid and late 20th century. Laura Ingalls Wilder evoking the life of the American prairie pioneers, that read almost like fantasy, but were historical reality; Mary Norton’s Borrowers, leaving every reader enthralled with the idea of an alternative universe under the floorboards. Philippa Pearce’s magical manipulation of time and place in Tom’s Midnight Garden; Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, illuminating the wild rumpus for all, young or old.

For so many, these and a host of other titles have been the initial escape from the prison of the self – the first amazing jump into an alternative set of events, the proposal of strangeness, difference.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The reading child becomes the reading adult. Many adults don’t read for pleasure; most, I rather fear. And in our age of the ubiquitous device, that is now apparently true of most children: a recent National Literacy Trust report revealed that just one in three children and young people aged 8-18 said that they enjoyed reading in their free time. Plenty of children don’t own a single book. I have just been reading of Bookbanks, the admirable organisation that puts free books into food banks. Help yourself to a book. But we have always had that, in the form of the public library system. And the child who grows up familiar with the local library is at once privileged, a reading child, and somebody whose life is going to be immeasurably enriched, a reading adult.

I was not one of those. I grew up in Egypt, with no access to any library. But there was an English-language bookshop in Cairo, and I remember treating that as a library, sneaking into a corner, taking down the book I had started last week, reading until called away. I was immersed in the works of Arthur Ransome, Swallows and Amazons and the rest, fascinated by this exotic world of children who sailed in boats in a landscape of water and greenery. I was absorbed, displaced for a while from my backdrop – to me, humdrum – of sugar-cane fields, palm trees and camels. The revelation of otherness, of time and space beyond your own, is the first prompt to the imagination.

The reason that fairy stories, myths, legends, were first of all for adults is that they suggested worlds, circumstances, in which things ran differently from the way in which most people’s lives played out; in which the wicked stepmother got her comeuppance; in which the scullery maid married the prince; in which you could find the crock of gold. They may be seen as fodder only for children now, but in the days of their conception the true value of story was understood: it has the power to suggest an alternative.

The writer of a children’s book has license to abandon time and place, to create, to propose alternatives

The writer of a children’s book has license to abandon time and place, to create, to propose alternatives

We seem to need stories, young or old. Film is story, much television is story, as is practically everything that is streamed. It long ago became a convention that many news items are identified as stories: “So-and-so has the story.” The distinction between fiction and reality has become blurred. In my Egyptian childhood, I was obsessed with Andrew Lang’s Tales of Troy and Greece, that retelling of the Homeric myth, so that for me the battles on the plain below the walls of Troy became vaguely identified with the tank battles in the Libyan desert that the grownups kept talking about; fact and fiction once again confused.

So, for me, what I experience, what I read, has always prompted a fictional response. I wrote for children before writing for adults; for both briefly, and then to my regret writing for children left me and it became for adults only. But I can see now how those children’s books were infused with the same adult interests and concerns as the novels I later wrote. The operation of memory, the presence of the past, conflicts of interest – these are themes that fuelled The Ghost of Thomas Kempe for children just as much as Moon Tiger for adults. I refused to write down to children as though they were another species, instead allowing them – intending them – to sense that behind and beyond the story they were reading were suggestions of something intriguing, a breath from the future, a hint of what they would one day know about.

When I offered my first novel for adults to my publisher, he was happy to publish, but suggested that we might think of doing so under another name. The implication was that since I was known as a children’s writer, a novel under my usual name might not be taken seriously. Obviously, I declined, and I think his attitude can’t have been a general one: the novel was shortlisted for the Booker. Nevertheless, there is an undercurrent of the attitude still around. Katherine Rundell – a marvellous instance of someone writing deftly for children and as a fine scholar for adults – quotes Martin Amis in her clever little book Why You Should Read Children’s Books, Even Though You Are So Old and Wise as having said: “If I had a serious brain injury I might well write a children’s book.” Oh dear. But I prefer to see this as outlier thinking – a notion the Booker foundation has confirmed with the establishment of a serious, grownup award.

It will be fascinating to see how this works out. Those writers already immersed in writing stories that I almost want to refer to as “so-called children’s books” will go on doing what they have always done. But there may be a change in how they are seen, and conceivably a surge of interest in children’s literature. Let’s hope so, and look forward to a future of fine writers, and, above all, more child readers.

Penelope Lively is the only author to have won both the Booker prize and the Carnegie medal for children’s books. She delivered a shorter version of this essay in her keynote speech at the Booker prize 2025 ceremony.

Illustration by John Tenniel from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland /Alamy

Portrait by Suki Dhanda for The Observer