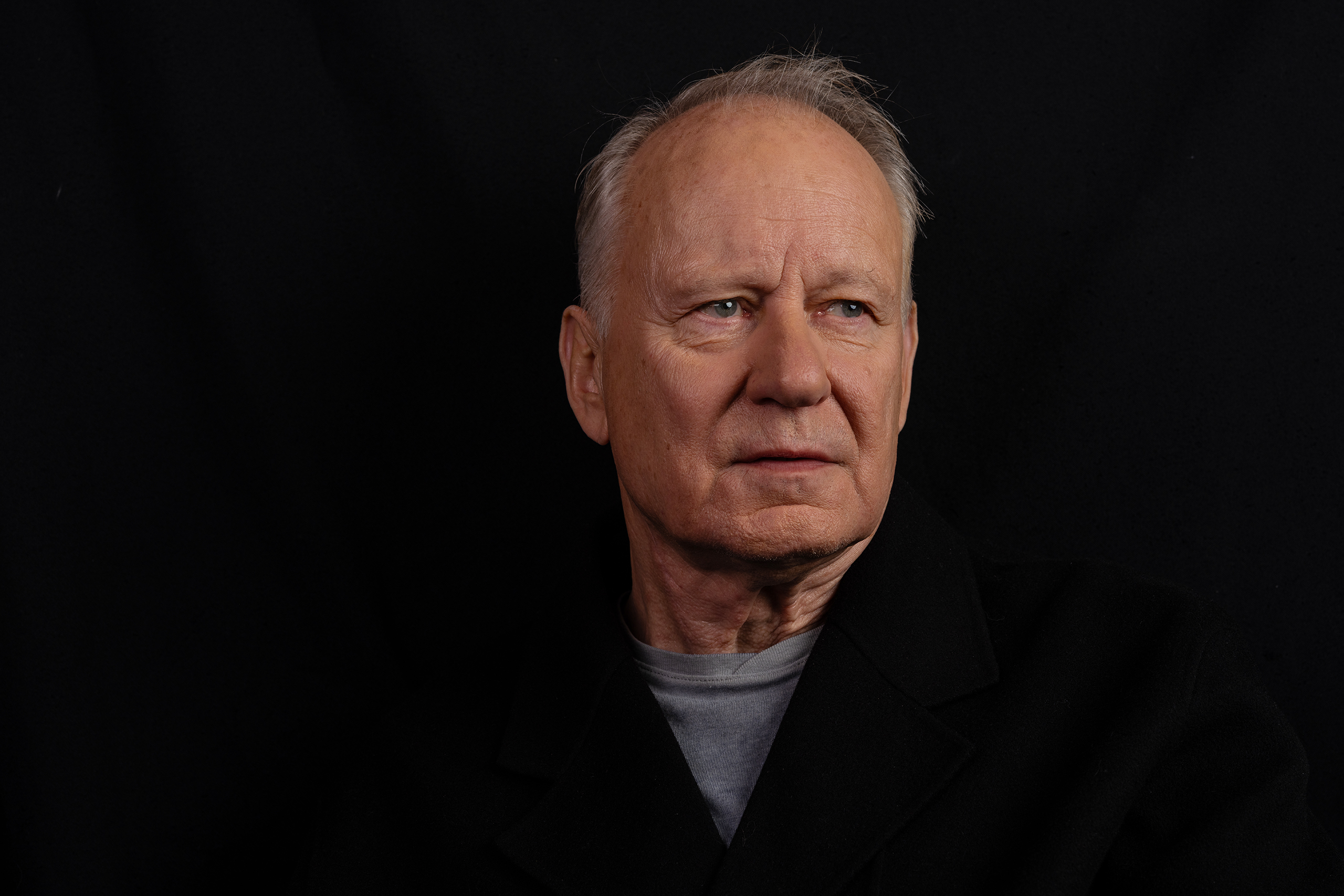

Photograph by Antonio Olmos

It’s now almost 30 years since Stellan Skarsgård came crashing into English-language cinema with Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves. Although he had already appeared six years earlier in The Hunt for Red October, it was his role as an oil rig worker who, disabled in an accident, sends his wife (played by Emily Watson) out to seek debasing sexual encounters that caused filmgoers beyond Scandinavia to take notice.

There was nothing look-at-me about his performance and yet it was impossible not to look at him. He had a transfixing cinematic presence, the kind that can’t be categorised or even properly explained but you know it when you see it. He was 45 at the time and had been a successful actor in his native Sweden since he was 16, but he displayed the freshness of a newcomer.

When I meet him at the Soho Hotel, he says: “I always try to be as good as an amateur,” by which he means as open and natural. “I can go to my technique and convince people, but that’s a lie because I’m really best when I don’t know what I’m doing and why I’m doing it.”

Perhaps it’s that uncertainty that makes Skarsgård so watchable. Whether he’s a maths professor in Good Will Hunting, a virginal voyeur in Nymphomaniac, a conflicted Soviet apparatchik in Chernobyl or Baron Harkonnen in a fat suit in Dune, he has an unerring ability to make the viewer wonder what will happen next, even when the script is busy hammering home the plot points.

Related articles:

In his latest film, Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value, he plays a once revered but monstrously egotistical director called Gustav Borg. Semi-estranged from the two daughters he abandoned many years before, Gustav wants to cast his talented actress daughter Nora (played by the brilliant Renate Reinsve, star of Trier’s previous film The Worst Person in the World) in a new film he has scripted. But it’s not clear if he’s trying to rebuild a paternal bridge or revive his moribund career.

To complicate matters, when Nora turns down the part he has written specifically for her, he recruits a young Hollywood star (Elle Fanning) and directs her with a fatherly tenderness that stands in confounding contrast to his insensitivity towards Nora.

It’s a compelling multilayered performance, by turns sad, pathetic, funny and tragic, which shows a man who has dedicated himself to his work at the expense of his relationships with his children. That’s a familiar story, of course, but Trier gives Reinsve and Skarsgård enough space to bring something piercingly distinctive to the scenario. The tension between father and daughter is not just familial but generational. In one scene, Gustav complains to Nora about the neediness of actresses, saying he would never have married one. “But fucking them was OK,” is her tart reply.

“Artists today are so petty bourgeois,” Gustav says in response. “You’ll never write Ulysses driving to soccer practice and comparing car insurance.”

It distils two moral perspectives. Gustav represents an earlier era when there was more sympathy for the idea that artistic creativity and chronic infidelity went hand-in-hand. Skarsgård himself began acting in the late 1960s, when libertine artists were given a lot of leeway. Does he think it’s possible to be a dedicated artist and a dedicated parent?

“Well,” he says, “to be a dedicated family person shouldn’t be confused with following social conventions. I like that line because it’s true in a way. But the answer is not yes or no. You have to balance it. It’s always a conflict.”

Since 1989, Skarsgård says, he has been at home for eight months of every year.

“But have I really been at home?” he asks. “I have eight children and some of them say: ‘I haven’t got enough attention from you.’ Some children need more attention than others. It’s very difficult.”

Stellan Skarsgård with Elle Fanning in Sentimental Value

Skarsgård had six children with his first wife My, a doctor. With the exception of Sam, who is also a doctor, all of them work in the film industry, mostly as actors, such as the high-profile Alexander, who played a tech billionaire in Succession and recently starred in gay biker movie Pillion. In 2009 Stellan married the American screenwriter Megan Everett, with whom he has two sons who have both worked as child actors.

One of his children, Gustaf (with an “f”), told him he had seen and admired Sentimental Value.

“‘Do you recognise yourself?’ he said. I said, ‘what do you mean? I’m a modern man. I’m not like Gustav!’ ... You can never satisfy your children,” Skarsgård says, “but that doesn’t mean you should neglect them. I never took my kids to football training, for instance, because I cannot stand it.” So maybe the line about soccer practice and not writing Ulysses spoke to him?

“I had no trouble saying it,” he laughs.

For some years Skarsgård has been dividing his time between well-paying character actor jobs in the US, where he has also been part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe juggernaut with Thor, and less lucrative lead roles in what remains of European arthouse cinema. Throughout he has remained living in Sweden, though he seldom works there nowadays. His children, he says, all live within walking distance of him in the same area of Stockholm.

In the past, he has said he likes the Swedish system of higher taxes and its more equitable healthcare and education. Although the country is not the social democratic utopia of foreigners’ romanticising, Skarsgård talks proudly of the Sweden of the 1970s, when the prime minister lived in a semi-detached house and walked the streets like anyone else, and “when even our big capitalists drove Volvos”.

He doesn’t like the growing inequality that has taken root since Sweden joined the neoliberal economic order, replacing the redistributive ethic of the Olof Palme days. But at the same time he never warmed to “the law of Jante”, a code invented by the Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose to describe a social stricture against anyone standing out.

Skarsgård has stood out ever since he starred as a 16-year-old in Bombi Bitt och jag, a kind of Swedish Huckleberry Finn, back when Sweden had only one TV channel. Before that he dreamed of becoming a diplomat: his boyhood hero was Dag Hammarskjöld, UN secretary-general from 1953 to 1961. But the revelatory experience of girls screaming at him in the street led to international cinema’s gain and international diplomacy’s loss.

Over the years Skarsgård has established himself as Sweden’s most recognisable and respected actor. From early on, his humanist parents instilled in him the idea that he was worth no more than anybody else, but also no less.

“Immediately when you become a public persona, a fictive person is created that is not you,” he says, describing the tendency to allocate to famous people either the tag of incorrigible sinner or blessed saint.

“To keep your sanity,” he says, “you must make sure that the difference between the persona and yourself never gets too big.”

At some point in their development, all Skarsgård’s children began to resent his fame. “Alexander said to me aged seven, ‘why can’t you be like all the other fathers and drive a Saab and work in data?’”

Obviously it didn’t deter him or his siblings from pursuing a career in which success means fame. In Sentimental Value, Nora has a deep-seated need for Gustav’s professional approval, despite rejecting his paternal overtures. Have Skarsgård’s children sought that same approval, and is something more required of a parent when their child follows them into the same trade? “Something more and something less,” he says, enigmatically.

His advice on managing the demands that come with a public image is “always do something they don’t expect”.

His own career has been true to that principle. You’d be hard-pressed to say what a stereotypical Skarsgård role looks like: he’s been in a number of films that seek to shock, particularly those of Lars von Trier, but he’s also been in Pirates of the Caribbean and Mamma Mia! The one constant is that he never seems to act in a predictable way. Instead he seems to bring an authentic sense of doubt to his characters, even when they’re brash, confident or, in the case of Gustav, blinkered by their own ambition.

Joachim Trier has called Skarsgård “one of the great Nordic actors of all time”, and the appreciation appears to be mutual.

“In the editing process, Joachim gets rid of all the narrative scaffolding, all the exposition, and what’s left is between the lines and in the silences,” he says. “That to me is movie acting.”

He doesn’t want specific direction from film-makers but rather “a looseness on set” in which things are not over-analysed “or reduced to the words”.

Some of the silences that pass between Skarsgård and Reinsve are electric.

“She’s incredible, fantastic,” he says. “One of a kind.”

To be a director you have to be like a pit bull. You have to bite and never let go. I don’t have the patience

Although his favourite place to be is on set, he isn’t particularly concerned about what happens to films after his work is done. “That’s the director’s job.”

Hasn’t he ever felt the desire to direct, to put forward his own vision rather than interpreting someone else’s? After all, as his latest film shows, he can certainly act like a great director.

“I did think about it,” he admits. “Probably all actors think about it at some time.”

He wrote a script with a friend and raised most of the funds needed to get to work on it, but then a producer took over, nothing much happened and he grew bored.

“I don’t have the patience,” he says. “To be a director you have to be like a pit bull. You have to bite and never let go. But I like being an actor. It’s faster work. I can do five films in the time it takes a director to do one.”

Skarsgård is arguably best known for his work with the other Trier, Lars von. From 1994’s The Kingdom to Nymphomaniac volumes I and II, he has featured in six of the Danish provocateur’s films. In the past he has said he agrees to anything Von Trier offers him without looking at the script. Apparently the director approached him with the idea of Nymphomaniac by telling him it was a porno flick.

“Yes Lars,” Skarsgård said, “I’ll be there, no problem.”

“But you will not get to fuck!” Von Trier teased.

“It’s fine Lars, I will come anyway.”

“But you will show your dick at the end and it will be very floppy.”

“That’s all right Lars, I’ll be there.”

Whether this relationship is built on schoolboy banter or a committed artistic relationship, the mutual understanding has survived several controversies. Perhaps the most notorious was the Cannes press conference for Melancholia in which the director, sitting on a table flanked by Skarsgård, Charlotte Gainsbourg, John Hurt and Kirsten Dunst, embarked on a lengthy riff about wrongly thinking he was Jewish, then discovering that his family had Nazi connections. “What can I say,” he concluded with a playful smirk, “I understand Hitler.” Throughout, Skarsgård looked earnestly at Von Trier, occasionally nodding, but no doubt wondering where it was all leading.

Von Trier has since been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and the plan had been to begin shooting last summer what is said to be his final film, entitled After. It’s said to examine death and Von Trier’s plight with Parkinson’s; Skarsgård was slated to be playing the lead.

But with Von Trier living parttime in a nursing home, the shooting hasn't happened. Are there any other directors he would particularly like to work with?

“There are lots of good directors,” he says, “and the one I most want to work with might not have done his or her first film yet.”

In any case, he says his choices are as much about the role and the rest of the cast.

In Sentimental Value there is a scene set at a press junket in which an obnoxious journalist attempts to goad Fanning’s character before surly Gustav comes to her defence and ends the interview. Such junkets, Skarsgård says, are “an offence to both our professions”.

Our own interview is, of course, part of a similar corporate publicity campaign of sorts, with its strict time slots and smooth-running PR machinery, but it is conducted in a far more civilised manner than that in the film, in no small part down to Skarsgård, his dry humour and thoughtful answers.

At 74, he retains an enthusiasm that can only be described as youthful and seems to possess the energy of a man half his age. What, I ask, is his fitness regime?

“I never sit,” he says. “I calculated how far I walked during the day on set and it was 40 kilometres. I walk around and around and people think I’m nervous. But I’m just sort of getting ready to go in and do it!”

Long may he keep doing it.

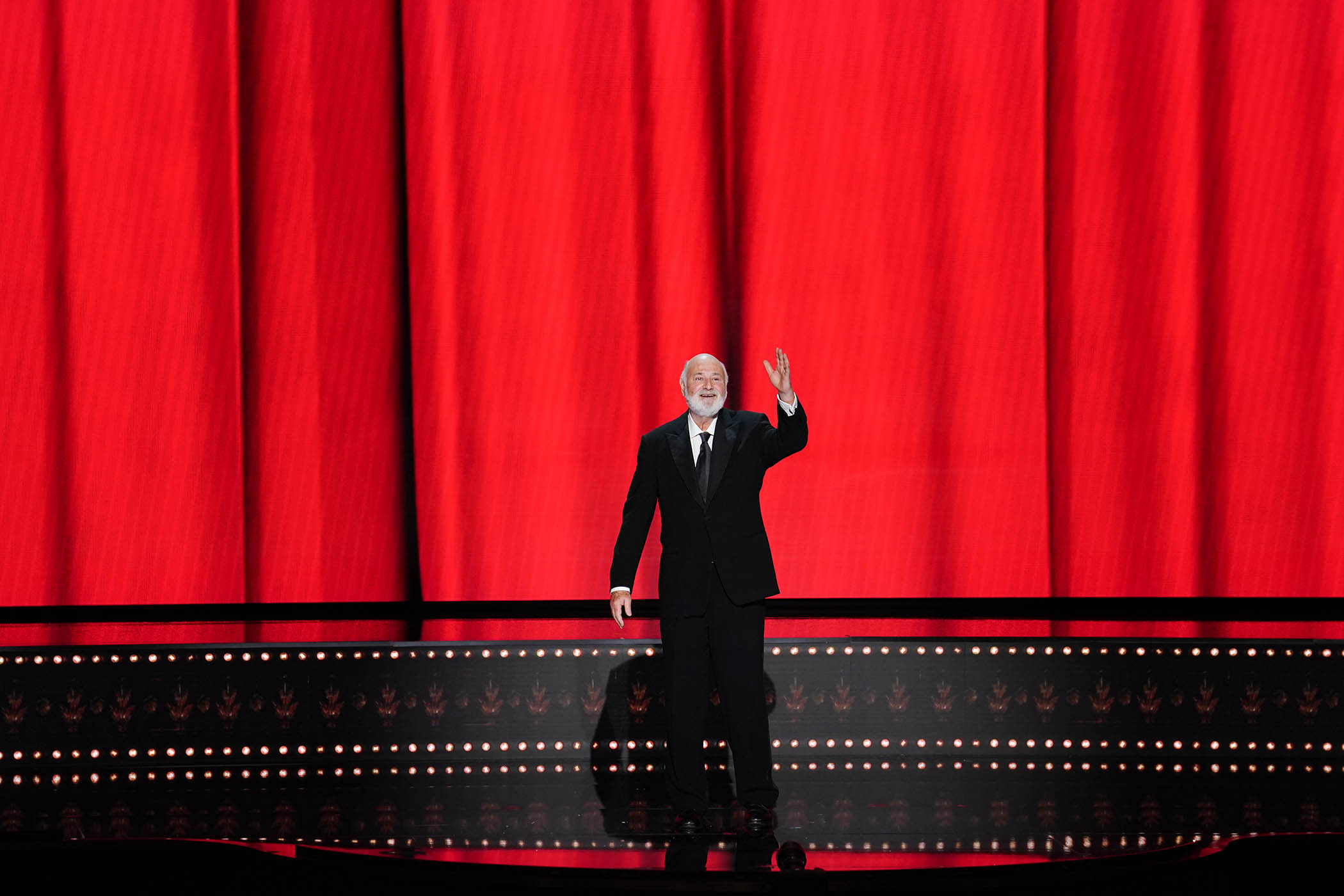

Photograph by Alamy