Towards the end of her long life, Jane Bown was in the habit of coming up to London each week from her Hampshire home to get her hair bobbed. Invariably, she would also come into The Observer’s offices on those Tuesdays to be among friends, and to remember the 60 years in which she had been the paper’s soul-stealing photographer. She was, by then, in a wheelchair, but she hadn’t stopped looking at the way the light fell on faces, always taking pictures in her head.

There was always something quite uncanny about that instinct, even before it became second nature. Jane had got her job at The Observer not long after the war. She once told me how it came about. “When we were demobbed from the Wrens in Bath,” she said, “and they gave us a list of possible jobs, I thought: ‘Photography sounds nice, I’ll go for that.’ There was only one course, at Guildford. My aunt gave me some money to buy a camera and I was off and running. Instead of learning about lights and so on, I could just see through that little square all sorts of things.”

She submitted a picture she had taken, a closeup of a cow’s eye on Dartmoor, to The Observer’s picture editor. “If she can find that depth of emotion in a cow’s eye,” he said, “then she can take photographs of people.” He took her on.

Over the subsequent decades, Jane’s pictures appeared in the paper each week. She was a very gifted street photographer, with the keenest instinct for quiet moments of everyday comedy and, despite her diminutive size, a sharp-elbowed newswoman. But it was as a portraitist that she made her name.

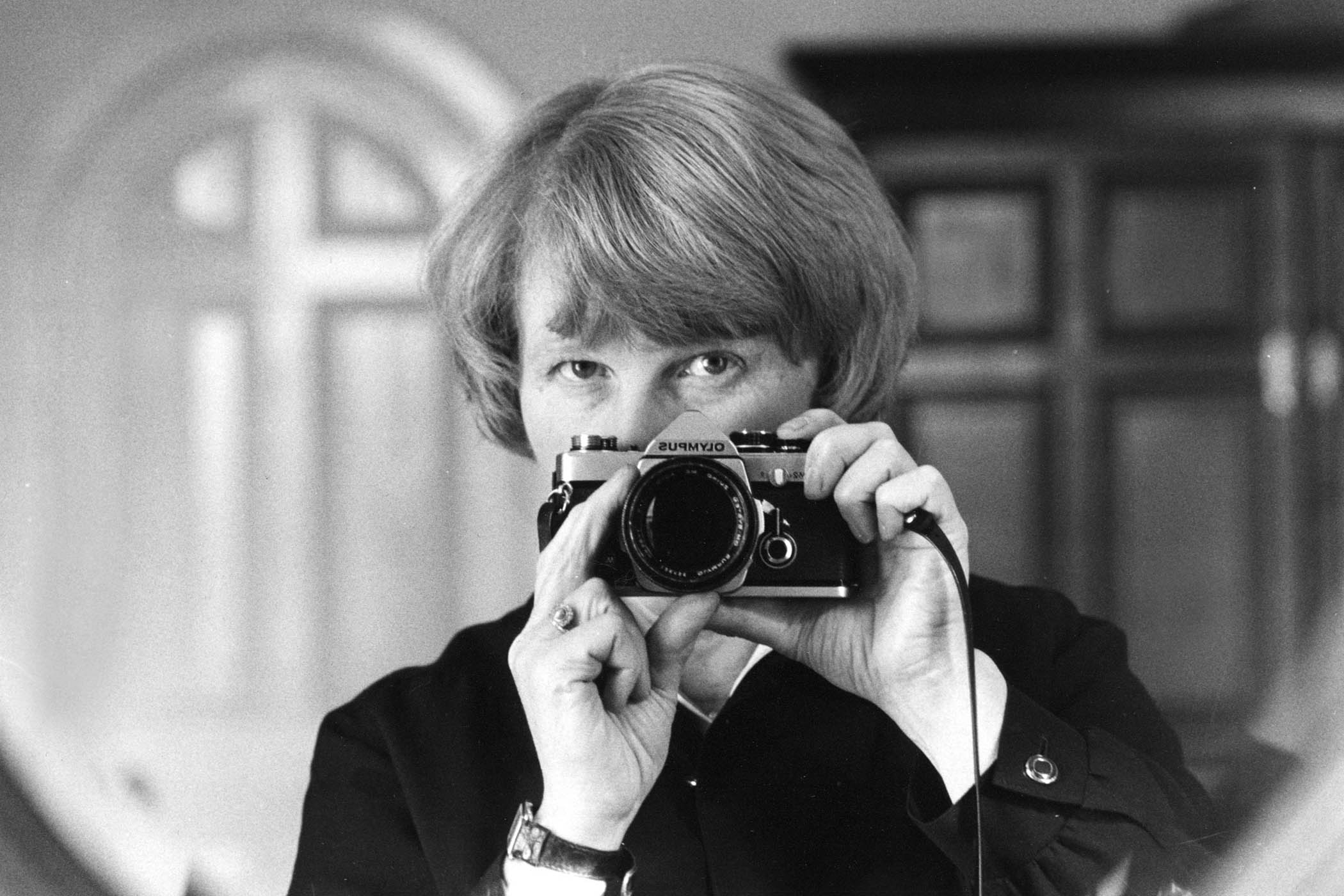

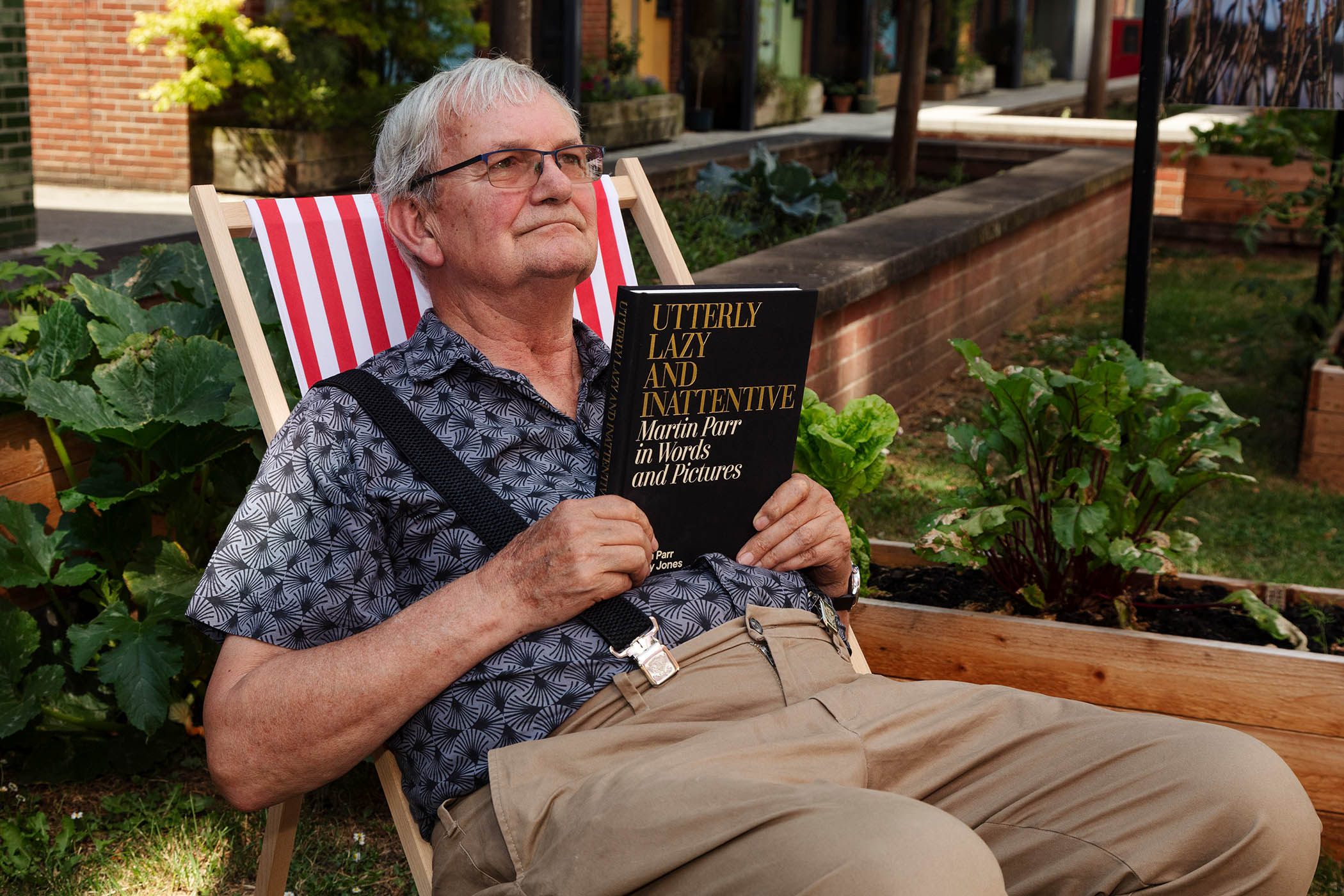

David Hockney, 1966. Main image: Jane Bown, self-portrait

She photographed everyone from Queen Elizabeth II (who chose Jane, her contemporary, to take her 80th birthday portrait) to rough sleepers. And she was the same with everyone, always carrying her battered cameras in a wicker shopping bag, an anglepoise her only concession to artificial light. Working with her, as I did on and off for many years, it was fascinating to watch her come alive around certain kinds of characters – often actors and musicians and artists – in the knowledge that, for a few charged minutes, she could make them fully themselves, and indelibly her own.

Related articles:

A new retrospective exhibition of Jane’s photographs opens this weekend at Newlands House in Petworth, West Sussex. On these pages are a selection of her portraits of visual artists from that show. Despite her gifts, it would never have occurred to her to think of them as kindred spirits. “Oh, I’m just a hack,” she would murmur, as she circled her subjects, alive to the play of light, and then she would seize her moment. “Oh,” she would exclaim suddenly, with her home counties vowels, raising her camera to her eye “there it is, that’s it, there you are.”

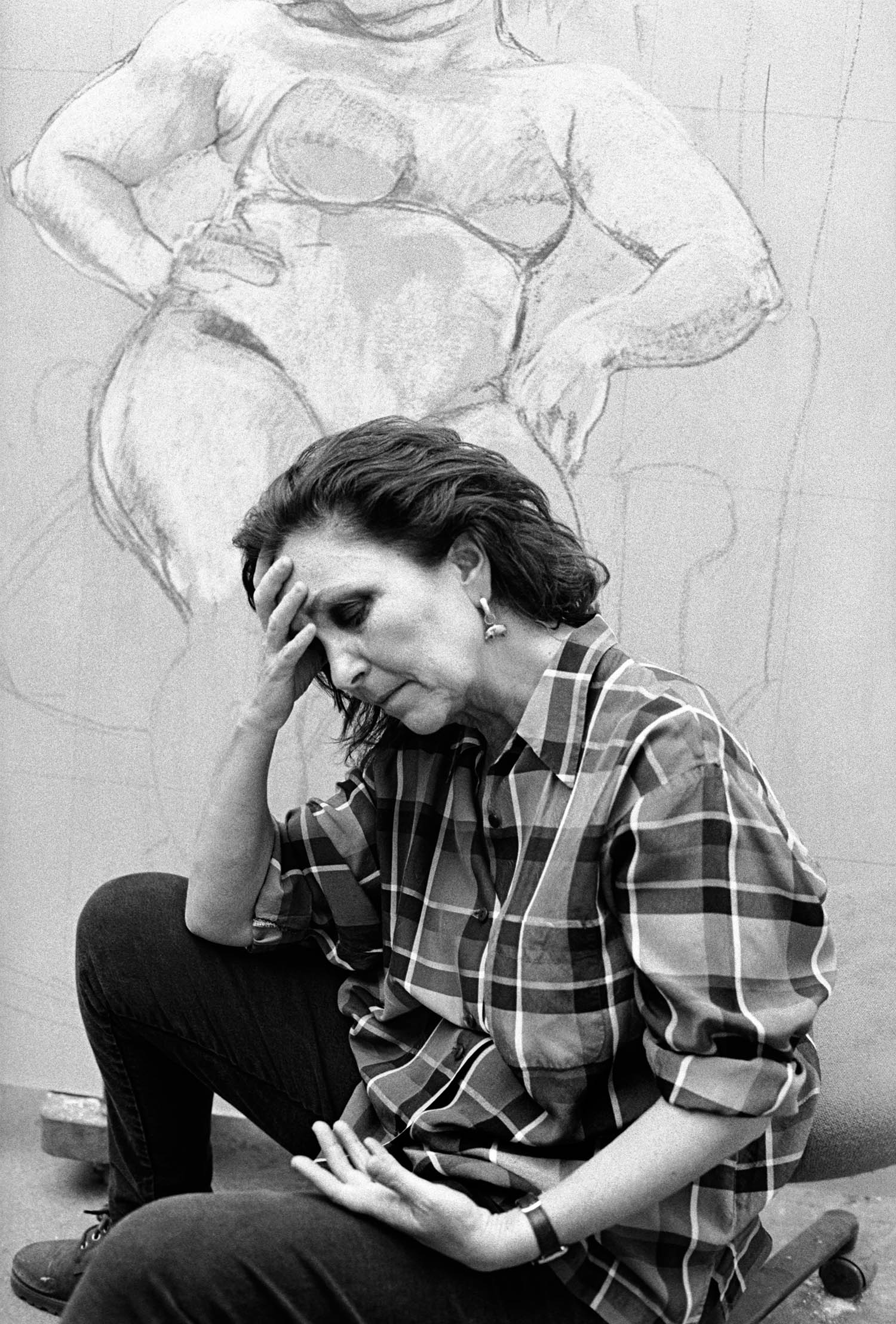

Paula Rego, 1995

Brassaï, 1982

Often, she would only use one roll of film, knowing that she had got what she came for. As her friend and archivist Luke Dodd recalls: “Jane’s whole aim in life was to find the light that would make f/2.8 aperture and a 1/60th of a second shutter speed work. That was all she ever wanted. There was something about that setting that she knew was perfect for what she needed to achieve…”

There were a few other tricks that she returned to. As Dodd says, she would work out ways to have her subject looking up at her; if she was in the office, she would take them out to the fire escape. “Jane understood instinctually that a face straining slightly upwards is more animated, the all-important eyes more open. Sometimes, it’s even possible to see a tiny image of Jane in the sitter’s pupil.”

She never stopped looking at the way light fell on faces, always taking pictures in her head

When she was not working, Jane had a nervous, birdlike quality in the office, waiting for that week’s assignment, fretting about whether things would go to plan. I would sometimes pick her up from her home, and all the way to the job she would worry about the shifting English weather, desperate for the light to hold. On those journeys , she was mostly reticent about her life beyond her work. Her default was a clipped kind of shyness, an apparent absence of ego.

When Jane was in her 80s, Dodd persuaded her to talk in a film about her early life. In it, she confessed that she had “been born on the wrong side of the blanket”. Her mother, she revealed, had been a young nurse to a country gentleman in his 60s and had become pregnant by him while working in the big house in Herefordshire where he lived with his wife and family. Jane was born on the kitchen floor and taken in by aunts. She met her father only once and had not reconciled with her mother before she died when Jane was 20.

Lucian Freud, 1982

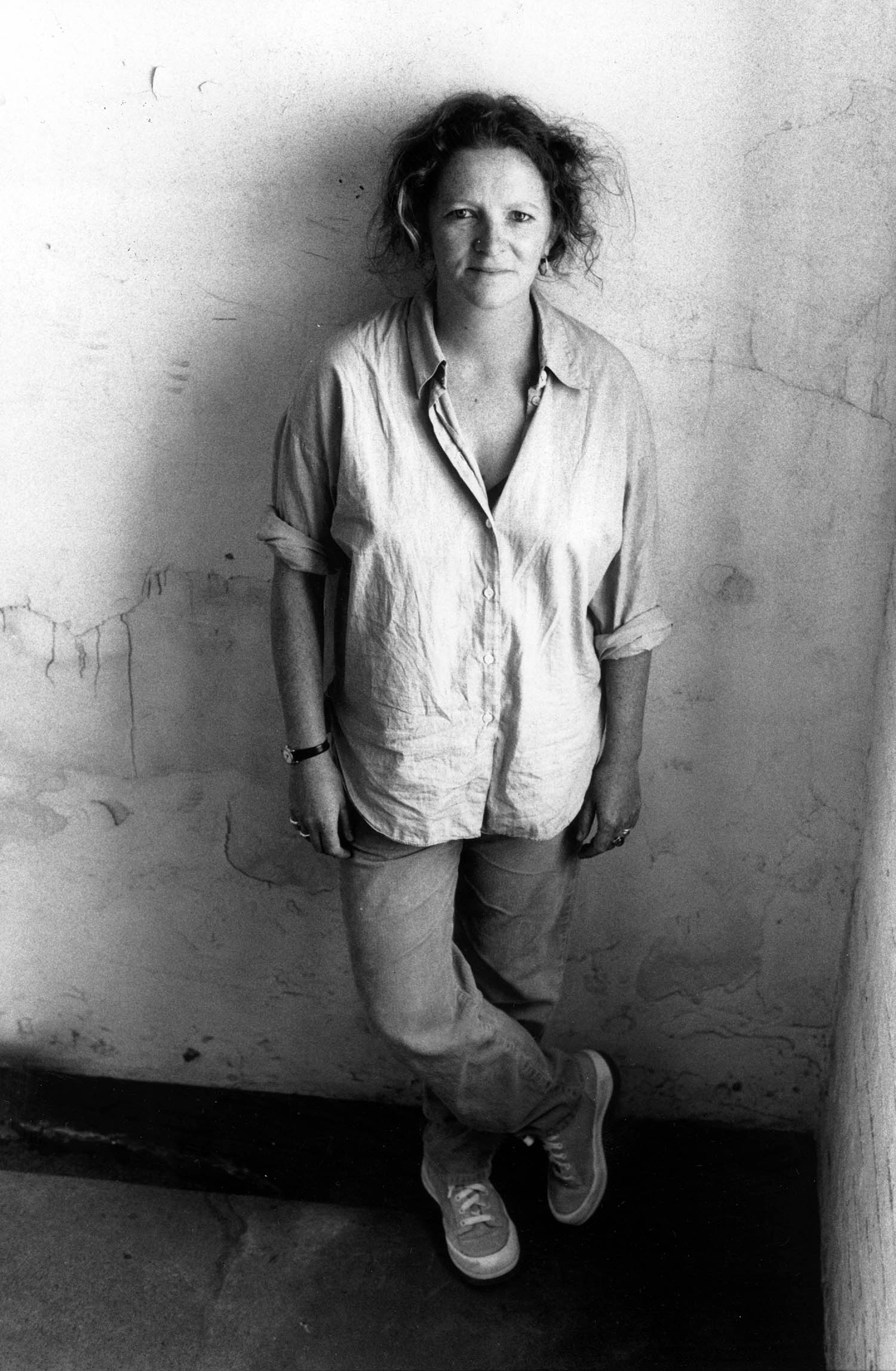

Rachel Whiteread, 1999

The film seemed to explain some of Jane’s character, and her genius. She’d always liked to say that The Observer was her family, though she had a husband and three children. “I used to wash my hair in the dark room and dry it under the drier in the film cabinet,” she would say. She had got used, because of the uncertainties of her upbringing, to “tacking myself on. I was very good at finding places where one more didn’t matter.” Her ability to be unobtrusive, yet to quickly establish intimacy, proved invaluable. When she first joined The Observer, Dodd recalls, in the heady days of David Astor’s editorship in the 50s, she would go to the pub, “and sip a gin and French [dry vermouth]” and enjoy watching the paper’s wilder spirits at play.

I imagine all journalists are drawn to their vocation, in part, for the vicarious insight it provides into the vivid lives of others. With Jane, that always felt a little like an addiction or a guilty pleasure. Dodd puts it down in part to a less than happy marriage. “I think Jane needed every week to go to work and have this really extremely intimate moment with a stranger [by photographing them], and then leave. And that was enough for her; it kind of recharged her, or made the rest of the week possible.”

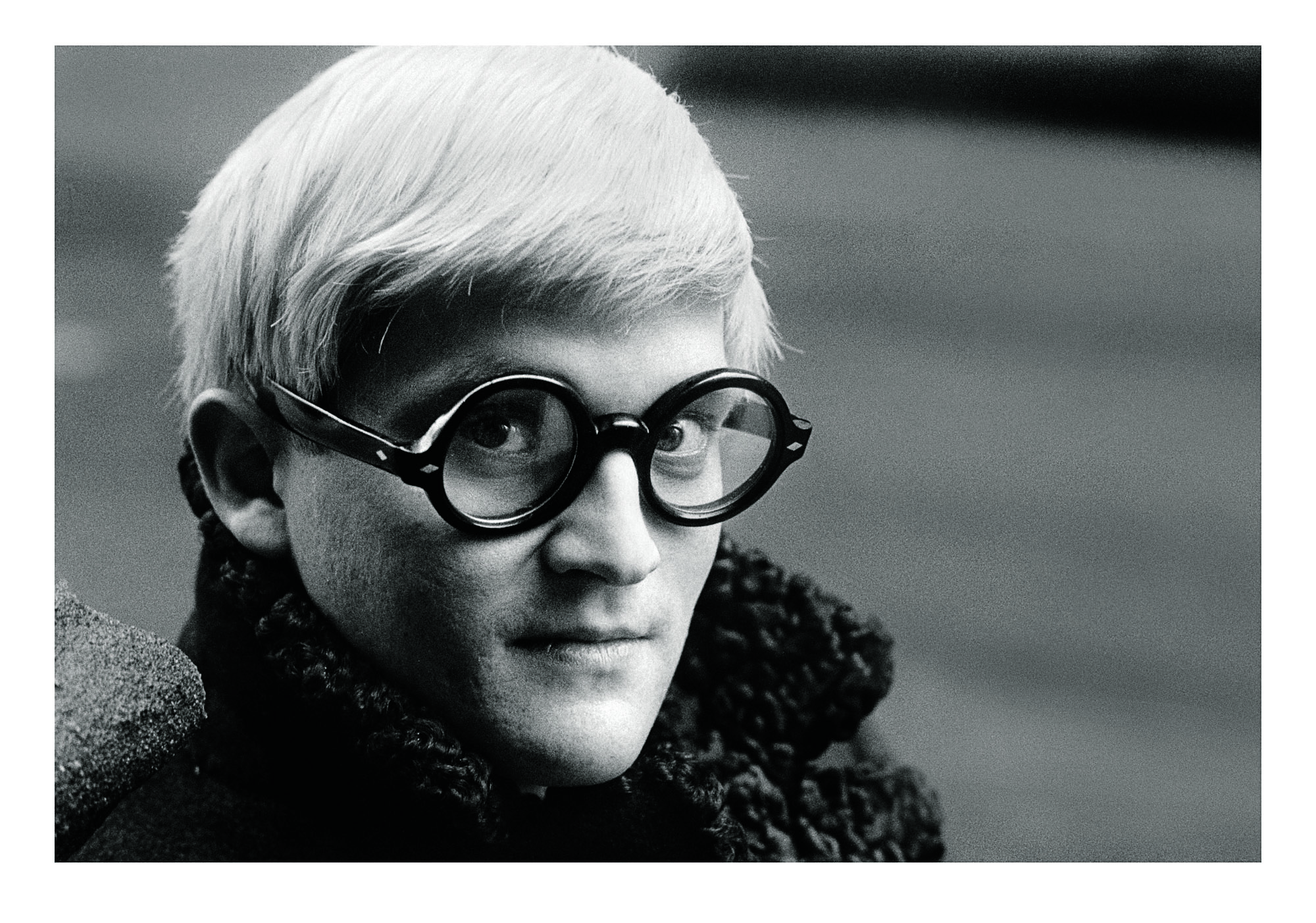

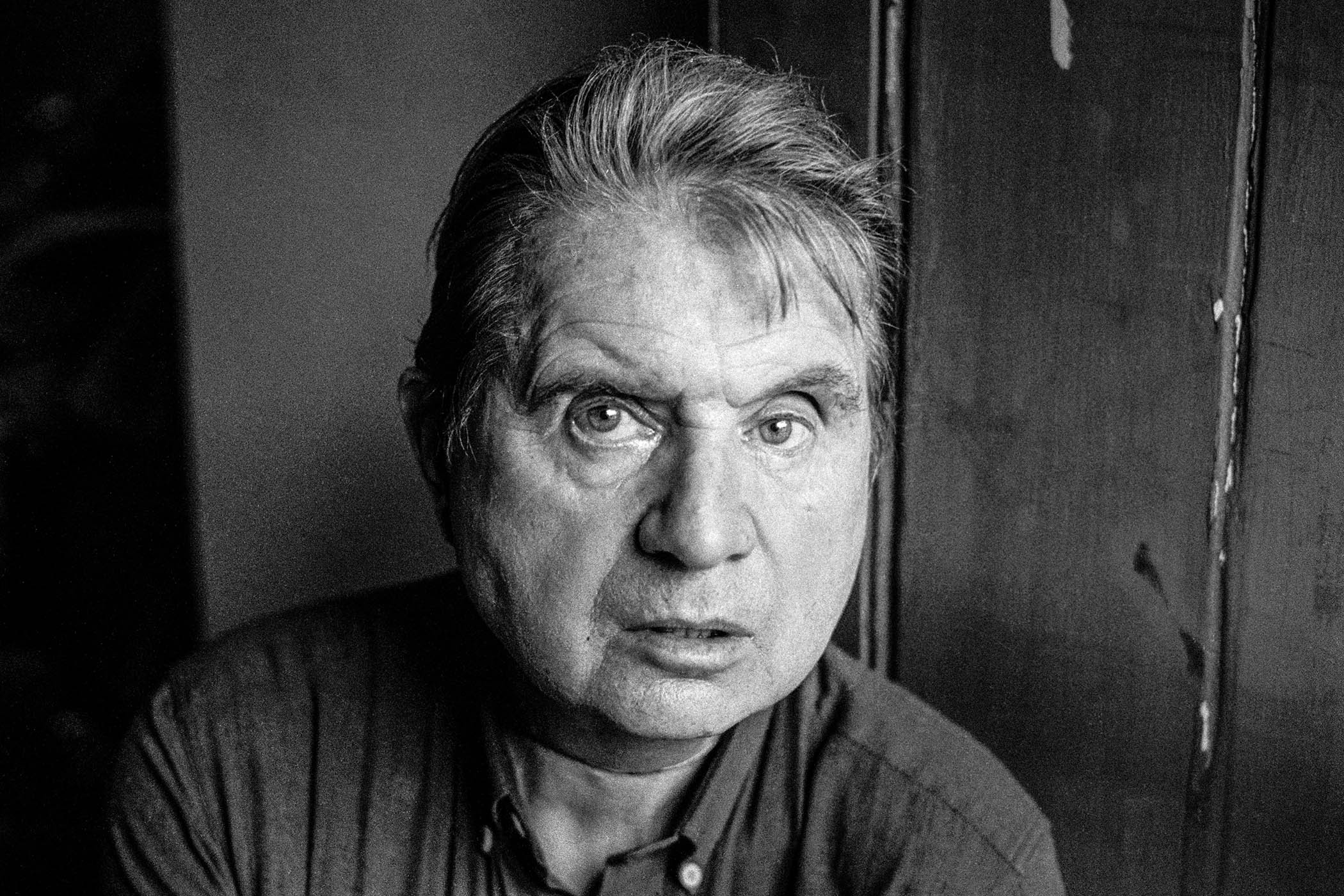

Francis Bacon, 1980

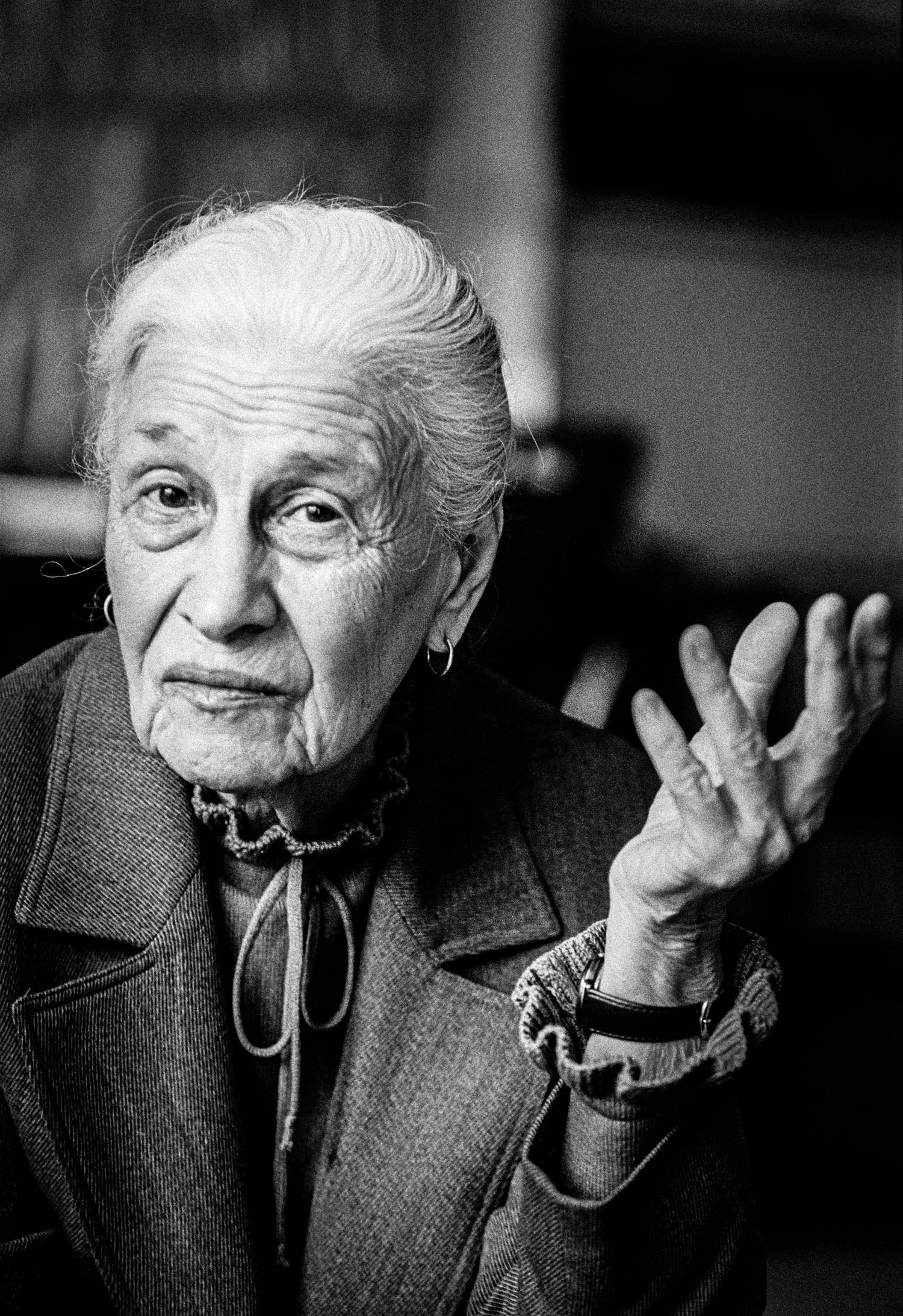

Eve Arnold, 1997

Jane didn’t keep in touch with the people she photographed, though many of them asked her to return to capture them again. It’s easy, looking at the faces on these pages, to see why they might have done so. Did David Hockney ever look more himself than in that picture, or Francis Bacon? Jane was always honest in her photographs, but never cruel. (Ever the pro, she always took both portrait and landscape shapes, to give page designers a choice.) She didn’t believe the bravado of some of her male peers. On the death of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who popularised the legend of the “decisive moment” to take a singular picture, she muttered to Dodd that it was a myth – she’d seen Cartier-Bresson’s negatives. “He walked along the street going click, click, click,” she said, not unkindly, “and then made it work in the darkroom.”

Not long before she died in 2014 at 89, I went to visit Jane in the Georgian house in Alton, Hampshire, where she had previously lived as a young wife and mother, and which she had later bought back and returned to live in as a widow. The house had once belonged to Jane Austen’s brother. She’d always liked, she said, to imagine the other Jane pulling up outside in a horse-drawn carriage.

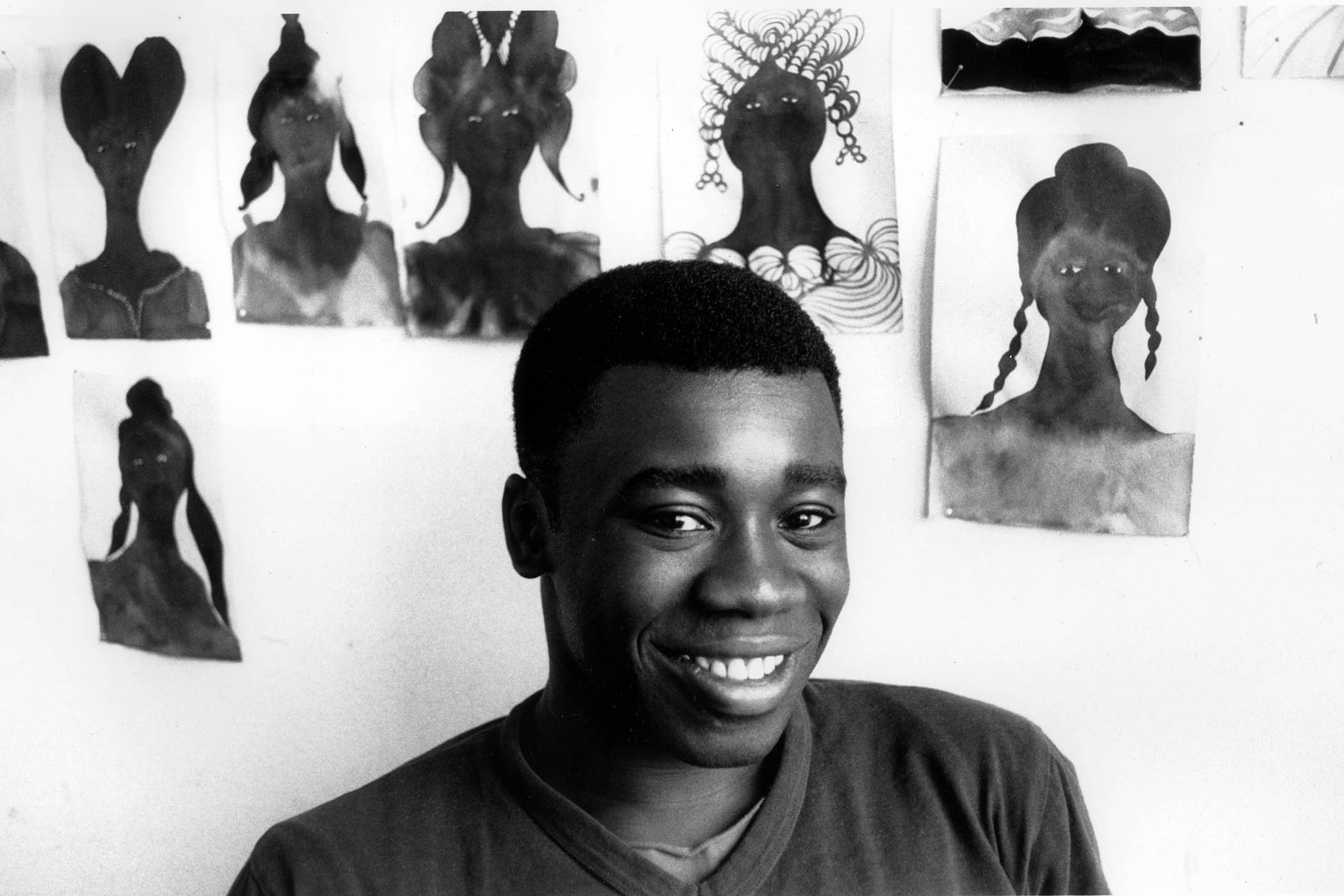

Chris Ofili, 1998

We had a mid-morning gin and French in a room overlooking a garden full of daffodils. On the walls were some of the portraits on these pages. When I asked Jane about her shyness, she pointed to the portrait of Lucian Freud – “I was shy of him,” she said, “and I think he was shy of me.” There was a story behind that picture, which was organised as part of an initiative with the British Council. Freud had been reluctant to submit to being photographed, but then he heard that Jane had also taken a picture of his great friend and rival Bacon. He couldn’t then refuse.

I asked Jane during that final conversation with her about the best of times, what had kept her going all these years? She gestured over at a pair of portraits on the wall; one of the singer PJ Harvey, and the other of Hockney, and smiled at the idea of them. “That’s what we want, flamboyance, a kind of exuberance,” she said. “I would latch on to that immediately, get a bit carried away. Yes, I was always looking for that energy. To try to catch it – if that makes sense. I could live off that.”

Photographs by Jane Bown/Camera Press