Illustration by David Foldvari

Where have all the manic pixie dream girls gone? Does anyone know? It used to be that you couldn’t move for them, at least in the canon of millennial coming of age movies. There was Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Natalie Portman in Garden State, Kirsten Dunst in Elizabethtown, Cara Delevingne in Paper Towns, Zooey Deschanel in 500 Days of Summer. And Zooey Deschanel in New Girl. Zooey Deschanel in anything, to be honest.

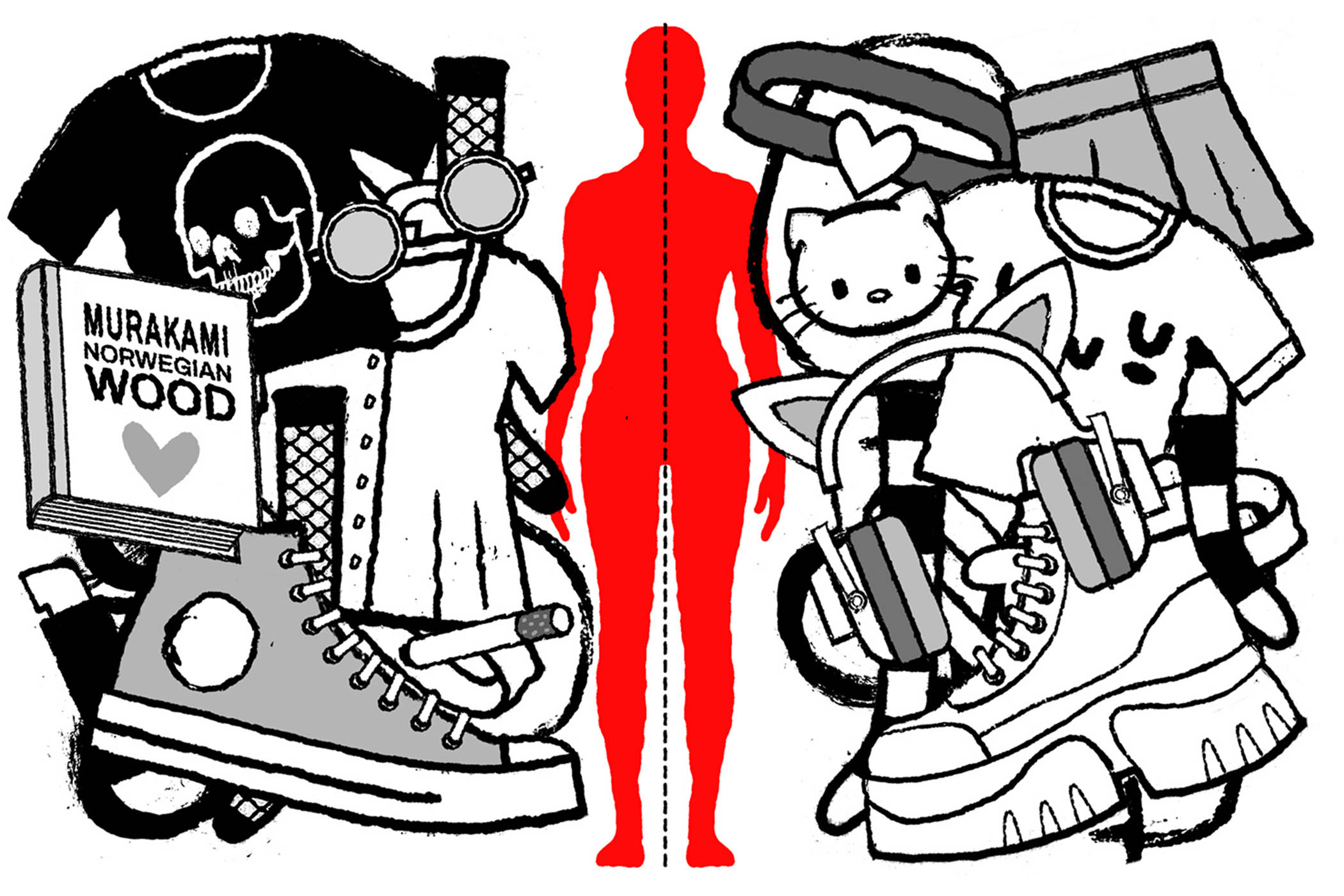

If you’ve got this far while wondering what a manic pixie dream girl is, then fair play for sticking with it. Here’s the explanation: the manic pixie dream girl (MPDG) is an eccentric but beautiful woman; a fantasy archetype. First defined in 2007 by the film critic Nathan Rabin, the MPDG “... exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures”. Her fashion sense is eclectic, brightly coloured and childlike, while still exuding – in a slightly sinister way, actually – coquettish sex appeal. She box-dyes her hair. She eats carbs, but remains impossibly thin. She invariably has a fringe. She occasionally transmits a mysterious sadness that will never be adequately investigated.

But the trope, while well-trodden, wasn’t beloved. She was ubiquitous, but she was endured rather than celebrated. Her invention – by awkward male writers and directors creating character conduits for themselves – was eventually held up as evidence of sexism in Hollywood. She was one-dimensional. She existed only to serve others, or more specifically only to serve one other, whatever man she was helping by bringing meaning and joie de vivre to his life. She provided emotional support, taught valuable life lessons, and got nothing in return. She only ever had two approved endings to her story: with the guy, or dead.

For real life millennial women, the MPDG was a cautionary tale. She was a trap to fall into. If you have a weird hobby (or really any hobby at all), wear a prom dress with trainers, watch films, read books, laugh, then suddenly the self-involved man you are having sex with will slot you into the MPDG box. Whether you were a real or fictional woman, you didn’t really decide to be an MPDG; you listened to The Shins once and were branded one. Or at least that was my experience. The MPDG’s very existence was inherently threatening: she’ll liven up your life, whether you like it or not.

She existed to serve whatever man she was helping by bringing meaning and joie de vivre to his life

She existed to serve whatever man she was helping by bringing meaning and joie de vivre to his life

Or at least she did, for a while. For millennials the MPDG was everywhere, but now she’s outre, nowhere to be found. Even her creator, Nathan Rabin, reviles and regrets his invention. In 2014, Rabin published an article in Salon in which he apologised for ever bringing her into the world. “The trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is a fundamentally sexist one,” he said, “since it makes women seem less like autonomous, independent entities than appealing props to help mopey, sad white men self-actualize.” He’s right! But eventually the MPDG became so overplayed in indie films that these days she’s all but vanished.

Which begs the question, what has replaced her, or what will? It would be nice to say that she’s been usurped by more complex female characters; by depth instead of single-dimension. And in some cases that’s true. When mania is explored in film today, it is increasingly done with care rather than merely being portrayed as a fetishistic character trait. Take the recent Jennifer Lawrence film Die My Love, a psychological drama about post-partum psychosis. Based on Ariana Harwicz’s novel, Lawrence’s production company took the script to female director Lynne Ramsay. Increasingly, women are telling female stories themselves.

Still, it would be too optimistic, too MPDG of me, to simply say that no reductive female stereotype has replaced MPDGs. Regrettably, she has a successor: the e-girl. The term emerged around the same time as the manic pixies (it was first used in the late 2000s as a pejorative term for women seeking attention on the internet), but the e-girl has risen where the pixies have fallen. This is a fully online subculture, not one created for movies and TV. Whereas MPDGs were annoying but vivacious, the e-girl is defined by a more subdued and submissive persona, both online and offline. Her clothes are darker, her music sadder; her manner sweeter and more innocent. Where millennial MPDGs had cardigans and Neutral Milk Hotel, the e-girl has Lil Peep and Belle Delphine-inspired cat ears. She’s Gen Z; millennials, now grownups, are not welcome here. But they’re (fine, we’re) too old to be manic pixie dream girls any more either. The millennial equivalent of the e-girl is the honey-blonde haired, milkmaid-dress wearing trad wife.

Related articles:

It strikes me that what both e-girls and trad wives share is that they’re meant to be demure, or quiet, or at least in the background for the main character, who is invariably a bloke. Which makes me wonder whether perhaps we’ve been too harsh on the manic pixie dream girl. Perhaps we’ve celebrated her demise too quickly. While we were dancing on her grave, we missed the fact that her spiritual successors are even more oppressed and miserable than she was at her peak. E-girls and trad wives, devoid of joy, are not going to inject meaning into anyone else’s life, because that’s not what they’re there for. The men attracted to these stereotypes are even less evolved than the sad millennial boys who fancied MPDGs. They’re not looking to women to give their lives meaning any more, but only because they’re told to discount them or hate them entirely instead.

The MPDG might have died rather than got the guy, but maybe her dubious legacy deserves some sort of eulogy. As a generational female stereotype, she was flattening and fetishistic – but at least she had fun.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy