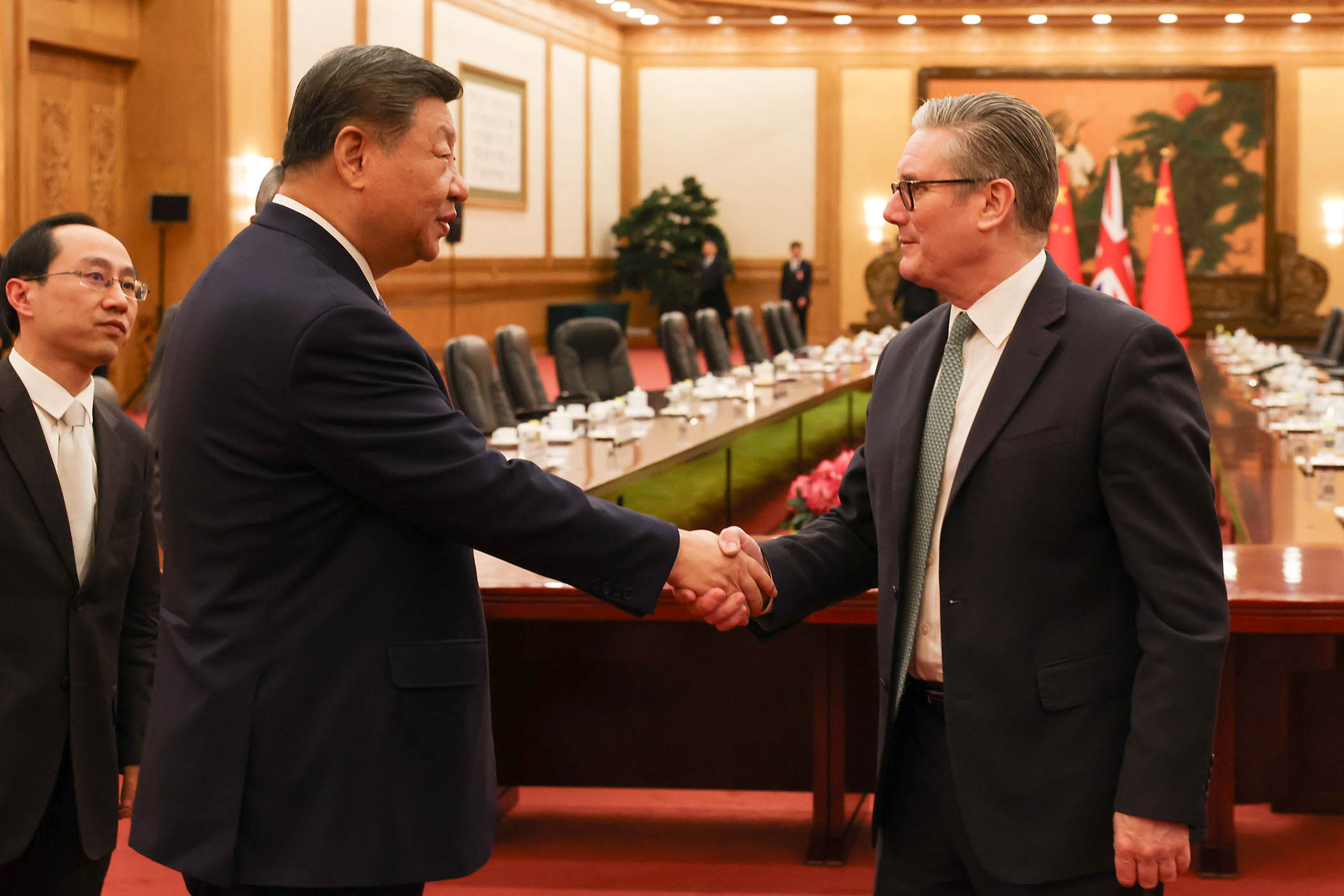

Keir Starmer’s briefing pack for his long-awaited trip to China is likely to have included at least a note about the turmoil in China’s formidable military machine.

On 24 January, news emerged of the dramatic purge from the Central Military Commission (CMC), China’s highest military body, of generals Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli, the last two CMC members promoted by Xi Jinping himself in 2022. The victim of a purge characteristically disappears from public view and, generally after an interval of silence that can last a year, his fate – expulsion from the party, imprisonment or execution – is announced.

What was striking about the disappearance of Zhang and Liu was how swiftly they were publicly denounced. Their departure leaves the CMC with just two members: Xi himself and the relatively junior figure of General Zhang Shengmin, who was promoted only last year and who oversees the Central Discipline Inspection Commission, the body charged with investigating corruption.

The fall of Zhang and Liu was so dramatic that it prompted a shower of speculation: Zhang had plotted a coup that was discovered by Xi, resulting in a major gunfight in a hotel in Beijing; the entire military was in a state of uproar; Zhang had leaked nuclear secrets to the US. None of these rumours have been substantiated but they speak to the importance of the moment and point to an information black hole that is as dark for most Chinese citizens as it is for outsiders.

Beyond the fact of the purge, there is little information. Of the two, Zhang’s downfall was the bigger shock, not least because he was viewed as one of Xi’s most trusted military allies. The pair have known each other since childhood: their respective fathers served in the People’s Liberation Army in pre-liberation days and Xi and his sisters at one point considered Zhang an honorary elder brother.

As he contemplates the next stage of his leadership, a troubling question for the Chinese president must be how can he tell who he can trust?

As he contemplates the next stage of his leadership, a troubling question for the Chinese president must be how can he tell who he can trust?

Was he corrupt? If he were not he would be an exception at senior levels in China. Zhang was directly responsible for military procurement from 2012 to 2017, years of huge military expenditure in China. But given that corruption is widespread, it’s unlikely to be the sole cause of his disgrace.

In 2022, Xi trusted Zhang enough not only to keep him on past the official retirement age but also to promote him to first-ranking vice chairman of the CMC. Last week, rather than be allowed to retire quietly, Zhang was denounced in long editorials in the official press that claimed that he and Liu had “seriously betrayed the trust and expectations of the Party Central Committee and the Central Military Commission, severely trampled on and undermined the chairman of the Central Military Commission’s responsibility system, seriously fostered political and corruption problems that undermined the party’s absolute leadership over the military and threatened the party’s ruling foundation, seriously damaged the image and prestige of the Central Military Commission, and severely impacted the political and ideological foundation for unity and progress among all officers and soldiers.”

The articles concluded: “They caused immense damage to the military’s political building, political ecology, and combat effectiveness, and had an extremely negative impact on the party, the country, and the military.”

Related articles:

Chinese president Xi Jinping leads CMC members during a visit to the revolutionary relics at Wangjiaping in Yan'an, northwest China's Shaanxi province, in 2024

These are strong words and speak to a serious confrontation. In China, the army is a party rather than a state organisation and, in theory, defers to the civilian party leader. But the armed forces have often been riven by factions in the past, and on occasion have challenged the party leadership. The most notorious case was that of the defence minister Lin Biao, who died in a plane crash in 1971 while attempting to flee to Moscow, allegedly following a failed coup attempt against Mao Zedong.

Zhang had been a key player in Xi’s long effort to modernise and clean up the armed forces. By 2017, Xi had completed an overdue military reorganisation and appeared to have brought the powerful armed forces back under civilian control. It would not be surprising that much of the money spent in the military modernisation effort should have failed to reach its intended destination, and the lamentable performance of the Russian military in the first months of the invasion of Ukraine no doubt prompted Xi to wonder if the shiny facade of China’s modernised armed forces also concealed a hollow interior. Several of the senior figures recently purged, including Zhang himself, were associated with key sectors such as procurement, an obvious opportunity for self-enrichment; others led China’s missile and nuclear programmes.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

There was a lot to clean up, including the long-established practice of buying and selling promotions, a feature of the party itself. This offered an opportunity to US intelligence, which in 2012 was discovered by its Chinese counterparts to have paid the promotion costs of officers who could be or become US assets.

Xi has been purging civilian and military leadership since 2013 in pursuit of an effective fighting force, and at a pace that has only accelerated. With his recent moves, he has purged an entire generation of the most senior military officers. He is not himself an army man, so he is now the supreme leader of a huge military organisation that he seems still to mistrust.

As he contemplates the next stage of his leadership, a troubling question for the Chinese president must be how can he tell who he can trust? An equally disturbing question for those he promotes, given his recent moves, is how can they avoid falling under suspicion, with potentially fatal consequences.

For Keir Starmer, looking through his Beijing briefing notes, turmoil in the Chinese military is a second order issue, except insofar as it might affect the odds of an armed assault on Taiwan. As things stand, such an assault seems unlikely, since it would be a huge gamble for Xi with global impacts.

But the army purge serves as a reminder that Chinese elite politics is a savage blood sport and that stability at the top is never a given, despite appearances. Mao Zedong maintained his position through regular purges; Xi has followed his example, and while the power to dispose of enemies is a useful element in the strongman’s handbook of power retention, it can also be a sign of self-destructive paranoia.

Xi’s wariness may have been heightened by a recent reminder of past dissent. In November, a seldom seen six-hour video appeared online of the trial of Xu Qinxian, the only general to refuse orders to disperse the 1989 Tiananmen Square protesters by force. “I wanted this to be handled better,” he said. “To solve it properly, to avoid conflict, to avoid bloodshed. [But] you brought weapons, tanks, armoured vehicles, machine guns.” Exiled from Beijing for life, Xu died in 2021.

Photograph by Ng Han Guan/AP, Li Gang/Xinhua