Well spoken, well tailored and well coiffured, Kevin Warsh looks how a Federal Reserve chair is supposed to look. At least to Donald Trump, anyway, who was keen to note Warsh was “central casting” in his social media post announcing the appointment. After a drawn-out selection process, investors seemed to like what they saw, too, with the US dollar rallying on what appears to be, at first glance, a conventional pick for a central bank head from an often unconventional president.

Few doubt Warsh’s apparent credentials. A banker by background, he has worked in policy and for a hedge fund, and has previous experience as an interest-rate setter at the Federal Reserve in the 2000s. In 2014, George Osborne, then chancellor, called him in to conduct a review of the Bank of England. Mark Carney, no fan of the current White House, hailed the choice after it was announced.

President Trump has a difficult relationship with America’s central bank. He has made no secret of his belief that interest rates should be materially lower than they currently are and appears to have no time for the usual niceties of avoiding making his preferences clear. In his first term as president, he regularly berated the then Fed boss, Janet Yellen, but over the past year his attacks have moved beyond the rhetorical.

The real worry for bond and currency markets is that a Federal Reserve concerned with keeping the president happy would result in inflation spiking

The real worry for bond and currency markets is that a Federal Reserve concerned with keeping the president happy would result in inflation spiking

His administration has attempted to remove governor Lisa Cook from the rate-setting Open Market Committee on spurious charges of mortgage misconduct, and appointed one of Trump’s own advisers to the board, and his justice department has subpoenaed the current head, Jerome Powell, alleging the mismanagement of a building refurbishment project.

For months, markets have feared that Trump would attempt to replace Powell, whose term is due to end, with a stooge prepared to ignore the outlook for inflation and simply cut interest rates to ease federal borrowing costs and buoy up the economy before November’s midterm elections.

The independence of the Fed itself has been seen as being under attack. The real worry for bond and currency markets is that a Federal Reserve more concerned with keeping the president happy than with the pace of price rises would result in inflation spiking higher. The end result would be lower bond prices and a weaker currency.

Hence the immediate relief, visible in the currency markets, at the Warsh announcement. Because while he might be close to Trump, he is also seen as traditionally holding more hawkish views on inflation. When he served as a Fed governor from 2006 to 2011, Warsh often argued for tighter monetary policy, and in the years since, he has argued that the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet and the policy of quantitative easing (electronically creating new money to buy government bonds) went too far.

Over the past 12 months, Warsh has towed the president’s line, publicly agreeing with him that interest rates should be lower. This, he has argued, is justified by faster US productivity growth driven, in part, by the development of artificial intelligence.

Related articles:

Investors currently expect some further modest rate cuts from the Fed and, in the near term at least, it is not hard to see Fed-White House relations being on a better footing than in 2025, while financial markets calm down about the risks to Fed independence.

This is unlikely to last. There is no way Warsh can cut rates as quickly as Trump desires while keeping the markets onboard. More likely is that Warsh’s hawkish instincts lead to him disappointing the White House, and a whole new round of political and verbal attacks on the Fed are unleashed.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It would not be the first time. Powell was himself appointed by Trump – beating out Warsh at the last moment – in 2017. As the president lamented in his rambling speech at Davos, the “problem is they change once they get the job”. President Trump clearly likes what he sees in Kevin Warsh. He may not enjoy how he goes about setting monetary policy.

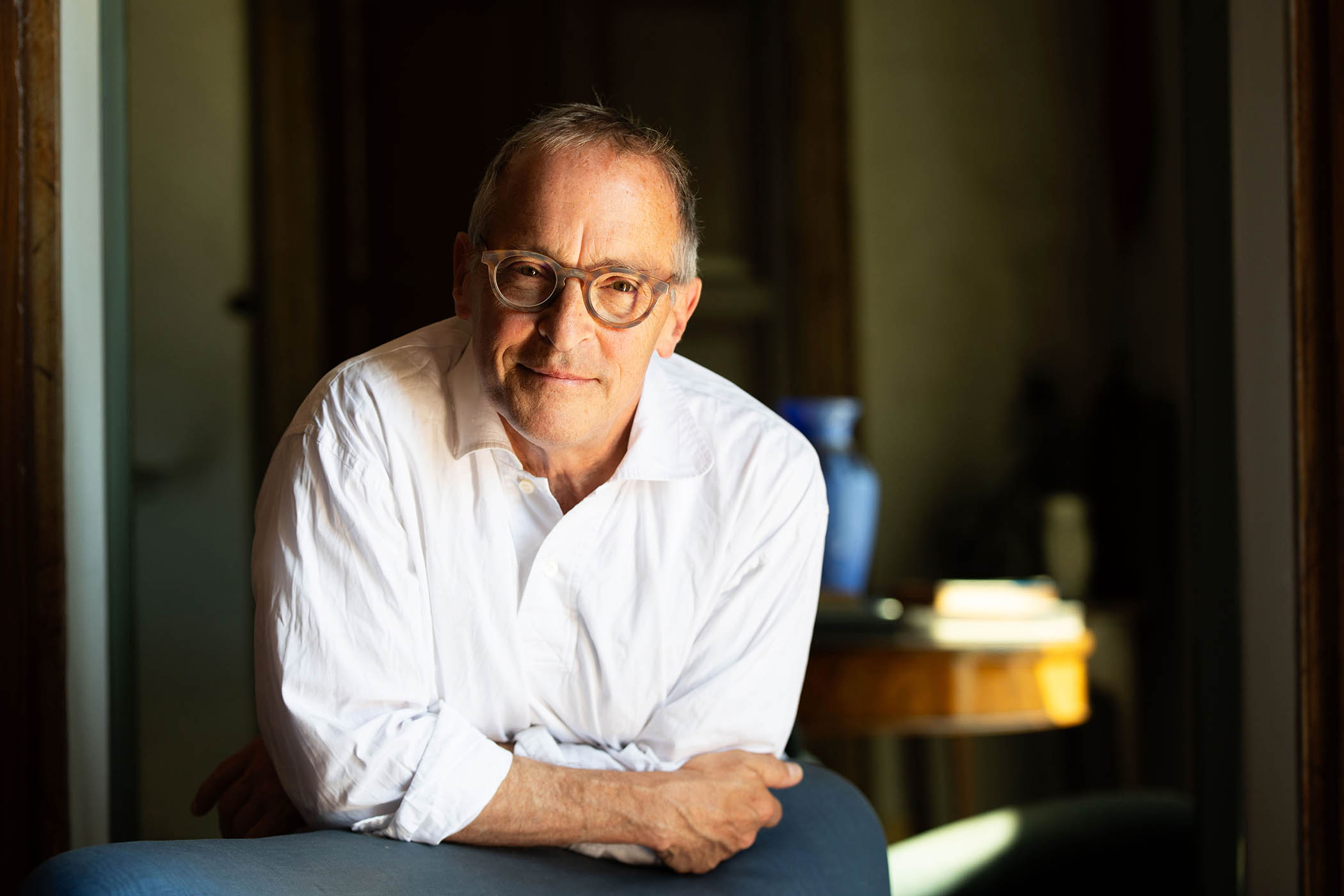

Duncan Weldon is an economist and author