Photographs by Oliver Marsden

Mahib Ullah’s four children had been dead a day before he found out. His son Waris, seven, and his girls Pekay, five, Spina, four, and Naziya, two, were killed instantly when a British airstrike hit the family home in Sangin, southern Afghanistan, in 2009.

His wife, Bibi Ayesha, was told months later that her children were dead, after she had come out of a coma. The explosion when the missile tore into the family’s mud and straw house sent her flying across the compound.

“We don’t know why the British bombed us. The Taliban were not in the fields opposite our home,” Ullah says, sweeping his hand over the parched fields of Helmand province. “They were over a mile away.”

Thin and quiet, Ullah wipes away a tear with his scarf as he recounts how he had been driving a taxi 60 miles away in Kandahar at the time of the strike. His neighbours rushed to the southern city to tell him what had happened. Meanwhile, British troops arrived at the site of the strike and took Ayesha to hospital.

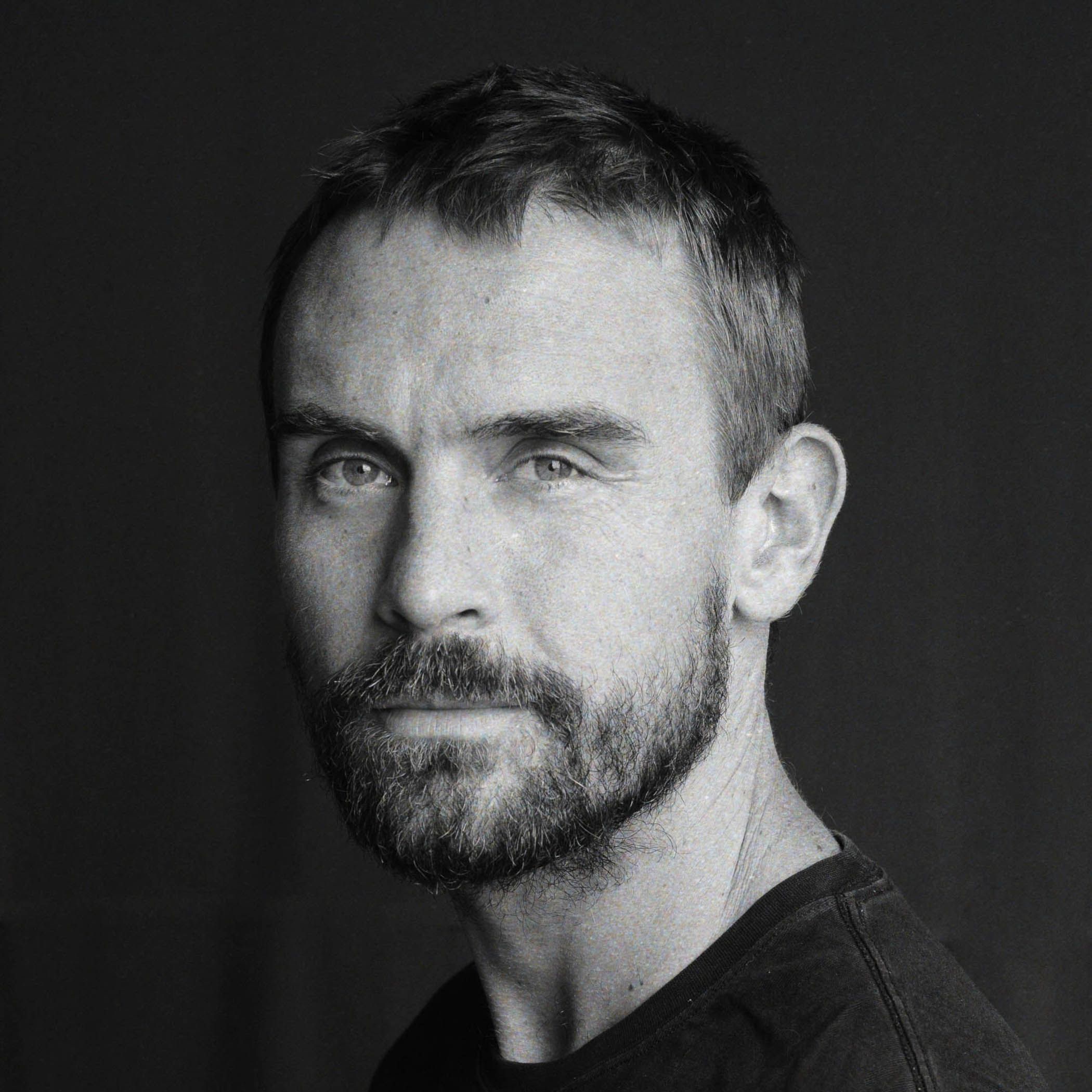

Mahib Ullah, whose four children were killed by a UK airstrike

“How can you describe your feelings when you hear all your children have been killed and your house destroyed? Years later and I still don’t have the words,” he cries. “The British forces didn’t offer us anything. No compensation, no apologies.”

It is almost 25 years since the US and UK invaded Afghanistan, 16 years since Ullah’s children were killed and four years since the west’s chaotic withdrawal. Outside Afghanistan the war is long forgotten. But for those like Ullah who suffered at the hands of the UK there is finally a glimmer of hope that there will be some accountability for these crimes.

Over the past three years the independent inquiry relating to Afghanistan has been hearing evidence of war crimes committed by special forces. Last week it heard damning testimony that evidence had been buried by senior officials. Britain’s conduct during the 20-year conflict is being dragged into the harsh light of scrutiny. Might there finally be a reckoning?

Related articles:

Today, Afghanistan is in flux. Power radiates from Kandahar, where the Taliban’s austere supreme leader issues edicts, while more pragmatic former fighters try to run the ministries in Kabul, the capital.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The economy is wrecked. Kabul’s streets are clogged with idle taxis, a testament to how little work there is. Women have all but vanished from public life, barred from most jobs and pushed out of sight.

A brutal, years-long drought has shrivelled the land, yet the capital still hums: restaurants are busy, shopfronts open, the women who are out wear fashionable abayas and fancy footwear. Shiny Land Cruisers prowl the streets. In a bitter twist, Afghanistan is safer than it has been in decades – largely because the men who once set off bombs and staged kidnappings are now in charge.

In the south, things are a little different. In Helmand, the marks of war are everywhere. The road from Lashkar Gah, the provincial capital, to Sangin is full of raised bumps of tarmac at odds with the surface preceding it. Each new section of road indicates where a roadside bomb had been detonated.

‘I was a very troubled young soldier. I made that decision to shoot the guy. It was a war crime’

‘I was a very troubled young soldier. I made that decision to shoot the guy. It was a war crime’

Former British soldier

Nowhere does the UK’s war in Afghanistan, and the damage done to both sides, feel more visceral than in Sangin. This harsh and arid confluence of the Musaqara and Helmand rivers was once the heart of the opium trade and a crucial part of the Taliban supply line. Shrapnel marks and bullet holes pepper almost every road, checkpoint and home. Crumbled buildings appear out of the dusty haze as monuments to the violence.

Between the US-led invasion in 2001 and the end of active combat operations in 2014, 453 British servicemen and women died in Afghanistan. Of those, 95% were killed between 2006 and 2012. In just one year – 2009 – 2,412 Afghan civilians died.

Haji Abbas casts his pale green eyes, lined with black kohl, over the stalls of Sangin market as his Toyota sedan bumps along the road. It’s easy for him to point out the exact spots where the IEDs had detonated because he was the one building them. A former fighter, Abbas is now the Taliban deputy in Sangin’s criminal investigations department.

“The Taliban used to move through the market to launch attacks,” Abbas says, dodging the young boys darting across the road in front of his car. “It was one of the deadliest places in the war for British soldiers.”

He recalled one attack in which an IED crippled a British convoy and left casualties in the dirt. In the aftermath, he says, the British gunners “opened fire at every living thing that moved”.

By 2010, as the violence flared, British forces’ morale had curdled into frustration, then anger, then something darker. Claims of extrajudicial killings began to surface – whispers at first, then formal allegations.

Members of the Taliban lie on the roof of a partially destroyed former military base on the road into Sangin

The Afghanistan inquiry was launched in 2022 following reports of unlawful activity and executions by the SAS – the UK’s special forces – of Afghan men held during deliberate detention operations between 2010 and 2013. They are also known as “kill or capture” raids.

On Monday, the inquiry released testimony from a senior ex-officer that two former chiefs of UK special forces buried evidence of alleged SAS war crimes.

Over the past month The Observer has spoken to former marines, brigadiers, ex-SAS members and war-crimes researchers – as well as to alleged victims. The former soldiers refused to be named for this story but all expressed concern that war crimes had been committed and the truth suppressed.

A trove of “significant action” logs – records of raids conducted by coalition forces in Helmand – was released under a freedom of information request and examined by The Observer. The Excel file contains 1,151 entries from 2010 to 2012. Several rows describe incidents in and around Sangin that match a disturbing pattern.

Shortly after 1am on a hot summer night 15 years ago, two Chinook helicopters lifted off from Kandahar airbase, where UK special forces were stationed, and descended on the fields near the home of Obeidullah Karim, three miles north of Sangin in Joshallay village.

Standing in his courtyard two weeks ago, Karim recalls the raid in precise detail. Soldiers blasted a hole in the eastern wall of the compound and took positions around the home.

All of the men were ordered out of the compound buildings. This is known as a “call-out procedure”. As Karim’s father, Haji Abdul Karim, and his brother, Habibullah, emerged unarmed, a soldier positioned on a roof threw a grenade towards them. Both were killed instantly. Shrapnel injured Karim’s mother, Badara, and his sister, Wasila.

Standing in the spot where his family members were killed, Karim runs his hand over shrapnel marks still visible in the earth wall. “They weren’t Taliban,” he says. “As the sun came up more British soldiers arrived in armoured vehicles. They said, ‘Forgive us, it was a mistake’, and left.”

Two and a half miles southwest of Joshallay, Sadiqallah’s home was raided by the SAS one night. The soldiers blew the door off the wall and entered the compound. They then called all the fighting-aged men out of the buildings. Sadiqallah’s son and nephew were handcuffed. According to Sadiqallah, the restrained men were then taken back into the house as the soldiers began their search of the building. His son and nephew were shot dead inside.

Records of SAS night raids in Afghanistan reflect the same pattern: men ordered out, then sent back in during searches. On more than one occasion, records state that moments before being killed the men were asked to open the curtains, the reason unclear, and that they then, inexplicably, reached for an AK-47 or grenade.

Haji Abdulrahman in the basement of Laljan House, where he says he was tortured

Chris Elliott, a war crimes researcher at the British Columbia Institute of Technology, told The Observer that “call-out procedures” were developed in Iraq during combined operations with US special forces. “Call-out procedures are a legitimate procedure to counter a legitimate threat,” Elliott said, pointing to documents now released into the public domain. “However, implausible stories emerge in the records. Invariably there would be a mad story about a grenade or gun hidden behind the curtains.”

The numbers of those dead and the numbers of weapons found do not add up either, he added.

“In one case, there were six enemies killed in action but only three AK-47 machine guns recovered. In another case the deceased-to-weapons ratio is nine to three,” Elliott said. “UK commanders were tracking at least 10 of these incidents before the deployment was even over. Call-out procedures appear to be the first step to then basically execution.”

These patterns were not unique to Britain. US Navy Seals, Rangers, Green Berets and Australian SAS units face similar allegations. A Human Rights Watch report documents CIA-backed Afghan units and US Rangers conducting nearly identical raids, with men separated from their families and summarily shot even when they offered no resistance.

British soldiers, meanwhile, complained throughout the war that captured Taliban fighters handed over to the Afghan national army were routinely freed through corruption. The SAS began to complain that the “capture” part of night raids was a waste of time, therefore the “kill” aspect was preferable.

At the IIA last week, the former senior officer said the stark imbalance between kill and capture rates suggested a calculated policy: fighting-age men were to be eliminated, not detained, irrespective of the threat they posed. Killing, he implied, was seen as the simpler route – removing suspects from the battlefield for good and sidestepping a judicial system no longer trusted to do so.

Perched on a hill above the road into Sangin sits Laljan House. Once a large private home, it was commandeered by UK forces. Bullet holes and shrapnel marks pock the walls and columns, inside and out. Among the battle scars sit scrawlings of graffiti by UK soldiers. Faded by 16 years of Afghan sun, a hand-drawn regimental cross of the Green Howards, often known as the Yorkshire Regiment, is still visible.

Underneath, written in permanent pen, “OP HERRICK 11” is still visible. Below, the names of a corporal, lance corporal and a private remain, with the rest obscured by bullet holes. “Operation Herrick” was the codename for British military operations in Afghanistan from 2002 to 2014, and “11” refers to its 11th rotation between September 2009 and April 2010.

Standing in the basement of Laljan House, Haji Abdulrahman describes how he was tortured there.

The 50-year-old says UK special forces snatched him from his home during a night raid and bundled him into the house. He recalls being beaten with a motorbike cable lock by men who spoke English with British accents. His legs were forced apart “by a man on each leg”, he says, and he was kept in darkness for three days.

He was accused of being a Taliban fighter who made suicide vests. “The UK soldiers wanted to know the locations and coordinates of suicide bombers and the factories,” he says.

Abdulrahman says he never confessed but he was in fact a Taliban fighter. He joined after his father and brother, neither a member of the Taliban, were killed by UK forces in Helmand. He wouldn’t answer whether or not he made suicide vests, but he told The Observer that due to family connections with both the Afghan national army and the British forces he was allowed to walk free. His smile never falters as he corroborates the frustration of UK forces.

A spokesman for the British Army told The Observer that it would welcome any evidence to support Haji Abdulrahman’s claims and would conduct any appropriate investigation.

Haji Abbas, in white, with other members of the Taliban criminal investigations department

An ex-soldier, speaking anonymously, recalled the relentless pressure in Sangin. A senior commander in Helmand echoed the same sentiment: you couldn’t grasp the reality of Afghanistan unless you lived it.

“Jumping out of helicopters, no sleep, months of rotation, fearing every step, asking yourself if you were going to die every time you entered a compound, firefights, patchy intelligence and then watching your friends lose their legs or their lives. It all took its toll.”

The weight of it eventually pushed the soldier past breaking point. A previous clash with the Taliban had left civilians dead at the hands of insurgents – people he’d been trying to protect – leaving him, in his own words, “incredibly angry and bitter”.

Later that year he watched a Taliban commander step from a compound carrying only a radio. Afghan troops beside the British patrol caught the message: the commander was telling his men to “hit” the soldiers.

Judging it an imminent threat, the soldier fired. The commander tumbled into an irrigation ditch, screaming into the handset that he’d “been hit. Hit them now!” What followed, the former soldier said, was that “all hell broke loose”.

Another unarmed fighter attempted to pull the commander to safety. As he heaved away, his head popped above the bank every few feet. The soldier waited for the next appearance and shot him.

“I was a very troubled young soldier at the time. I made that decision on the ground to shoot this guy,” he says. “But essentially, that is a war crime… he was unarmed and was evacuating someone else.”

The main question for the ex-soldier now is: “Why? What was it all for?” To date, only one British service member has been prosecuted for a war crime in Afghanistan. No member of UK special forces has been tried or charged.

Back in Sangin, as the afternoon sun begins to fade, Ullah turns away from the fields and the river and gazes at the spot where the British bomb had hit his home.

“My children are buried on the other side of the village,” he says softly. “I carried the bodies of my dead children all the way across the river, trying to find a peaceful place to bury them.”

Ullah looks up and asks the same question as the ex-soldier, the question echoing across the wreckage of a 20-year war and the scars of Sangin: “I want to know why this happened? What was it for? We are civilians. I just want to know, why they did that to us?”