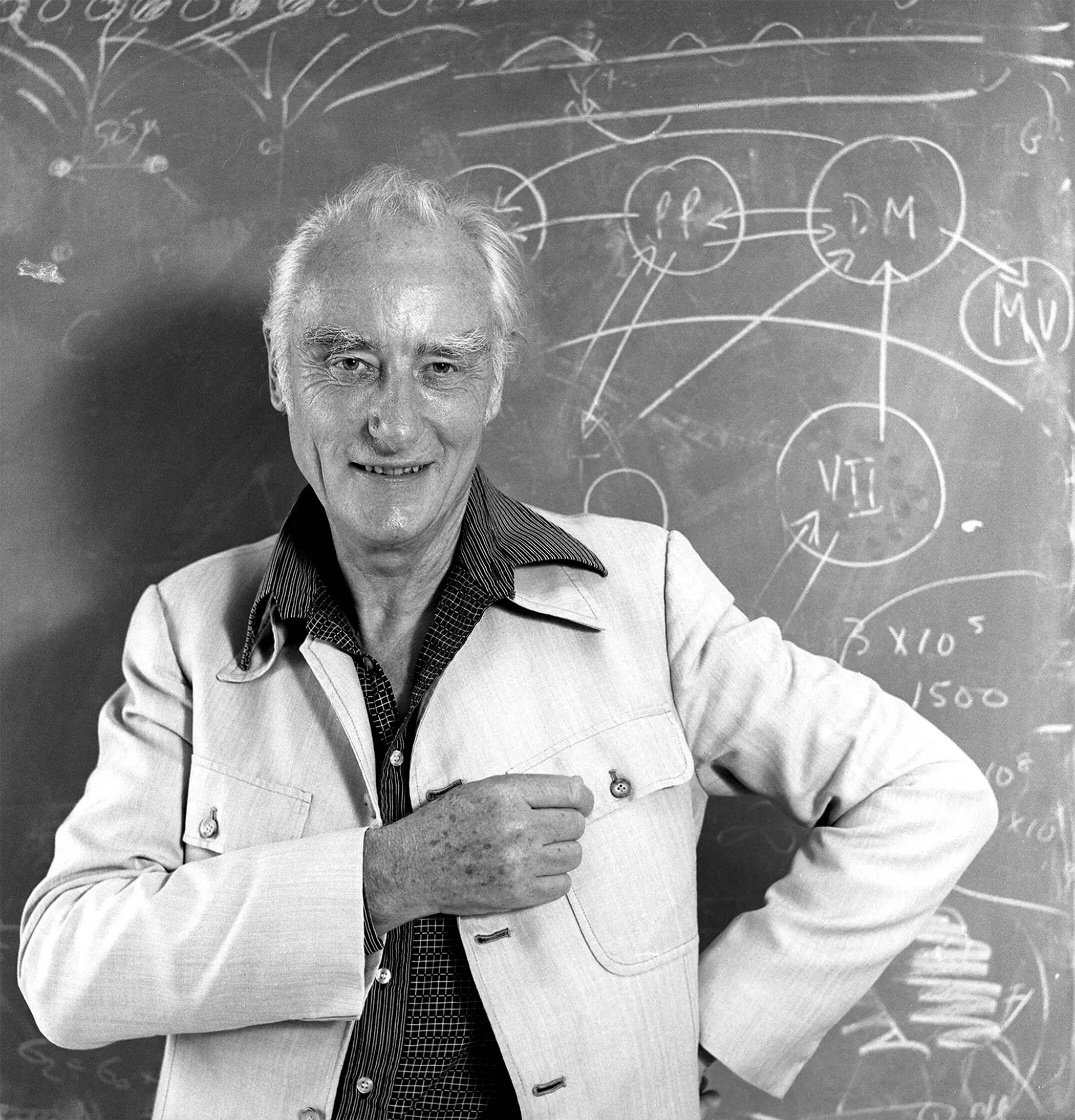

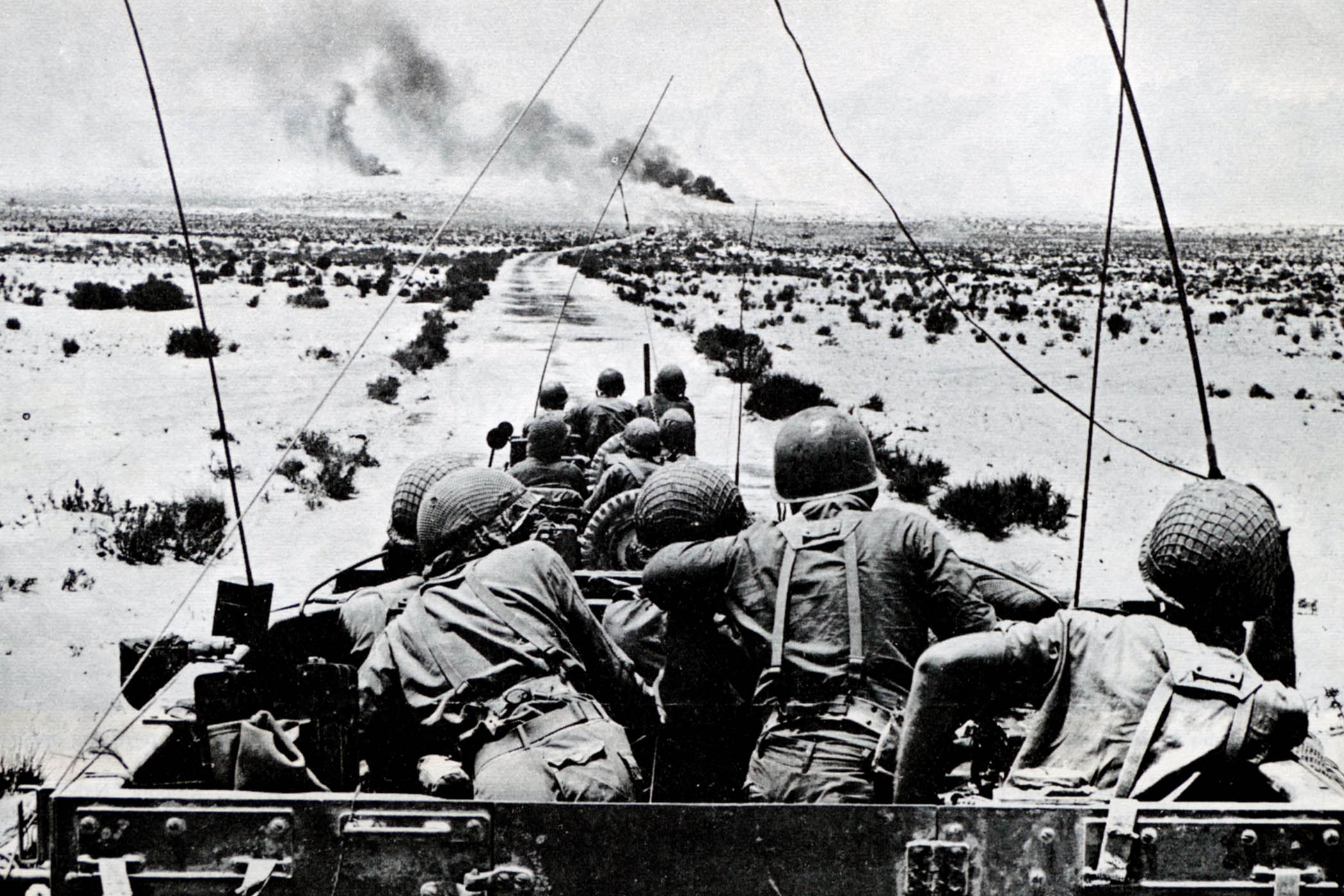

In 1947, aged 31 and with his career in physics derailed by the war, Francis Crick, the future co-discoverer of the DNA double helix, returned to research, focusing on two fundamental biological problems: life and the brain. Over the following half century, he made decisive contributions to both these fields, becoming one of the most significant thinkers of the 20th century. In 1994, the Times hailed Crick as the “genius of our age”, comparing him to Isaac Newton, Mozart and Shakespeare, while after his death in 2004, parallels were drawn with Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel.

Like Darwin, Mendel and Newton, Crick changed how the rest of us see the world. He drew out the implications of DNA structure, developed new ways of understanding life and evolution, and later convinced neuroscientists to adopt computational and molecular approaches, and to study the nature of consciousness.

Crick’s aim was not just to make discoveries about two fundamental scientific riddles; he also wanted to replace the superstitious and religious ideas that marked these questions. This did not mean he was stuffy or unimaginative – he was fascinated by the flux of perception and emotion he found in poetry, particularly the work of psychedelic Beat poet Michael McClure, who became a close friend. Poetry and science co-existed in his approach to the world.

Crick’s scientific achievements have recently tended to be reduced to those few weeks in Cambridge in February 1953, when he and James Watson discovered the structure of DNA. The widely believed story that they stole the data of King’s College London researcher Rosalind Franklin is untrue: Watson and Crick knew of Franklin’s results and those of Crick’s close friend Maurice Wilkins, but they did not provide any decisive insight into the structure of DNA. Franklin knew that the pair had access to her data and bore no grudge; she soon became friendly with both men, and was particularly close to Crick and his wife, Odile.

Watson and Crick subsequently explained that had they not found the structure, then Franklin, or her colleague Wilkins, or someone else, would have done so – it was inevitable. Crick and Watson succeeded because they were lucky, smart, somewhat unscrupulous, and determined.

In 1961, Crick argued that “adventurousness” – a willingness to explore unorthodox solutions – was also important in the discovery. Such leaps are easier if you have a collaborator to say that you have jumped too far, or to encourage you in the right direction. That style of intense, collaborative working eventually enabled Crick to think further and deeper than most of his contemporaries

Odile recalled that during the exciting days of February 1953, “Francis was think think think”. He was also talk talk talk. Virtually none of Crick’s ideas were his alone; unusually for a scientist, he always had an intellectual foil against whom he could bounce his ideas. These people were always younger than him, most were men, and they often had a different background. His work with Watson lasted only a few months – much more significant were his decades-long interactions first with South African molecular biologist Sydney Brenner and then with the German-American neuroscientist Christof Koch.

Brenner described their freewheeling discussions: “The thing we did have was a rule that you could say anything that would come into your head. Most of these conversations were complete nonsense but every now and then… a half-formed idea could be taken up by the other one and refined.”

Related articles:

Such candid exchanges often involved tough criticism. “You must of course try to attack the other person’s ideas,” Crick explained, “because it’s getting rid of the false ideas that is the most important thing in developing the good ones.”

One of Crick and Brenner’s key interactions came in 1960, when they suddenly realised that a series of confusing experiments could be explained by viewing genetic information as a message that was read by the cell – a breakthrough that changed our understanding of gene function. French researcher François Jacob was there and described events in his memoir:

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“Francis and Sydney leaped to their feet. Began to gesticulate. To argue at top speed in great agitation. A red-faced Francis. A Sydney with bristling eyebrows. The two talked at once, all but shouting. Each trying to anticipate the other… All this at a clip that left my English far behind.”

Through this kind of furious discussion, Crick honed his theories. He explained that developing these ideas relied on intuition, that near-magical quality based on unstated, implicit knowledge and a rapid, unconscious exploration of possibilities.

The imaginative aspect to Crick’s thinking extended to his vocabulary. In 1953, he told a friend that the double helix made him swoon every time he thought of it; this was because of its beauty, a term he often used rather than the word “elegance”, frequently employed by physicists and mathematicians. Biological results are often messy and complex, not elegant. They are nevertheless beautiful, because of their evolutionary roots and the contingent factors that have shaped them.

This sense of beauty, of deep relationships underlying complex phenomena, drove Crick’s scientific work and was linked to his fascination with poetry. As he explained:

“I hope nobody still thinks that scientists are dull, unimaginative people… It is almost true that science itself is poetry enough for them. But there is no effective substitute for the subtle interplay of words and from time to time one becomes wearied by the exact formulations of science and longs for a poetry which speaks to one’s bones.”

Although Crick admired the works of WB Yeats and TS Eliot, by the mid-1960s he had fallen out of love with them because of their mystical views. As he explained in a letter to his friend, the novelist CP Snow, he felt “you can’t be a major poet without a solid foundation of silly ideas (almost everybody thinks Yeats’s ideas silly but to me Eliot’s are just as bad)”.

Crick’s letter to Snow came at the height of what was known as the “two cultures” debate, after the title of a lecture given by Snow in 1959. Snow highlighted that while a knowledge of the arts was assumed essential for a well-rounded education, many intellectuals, civil servants and politicians were profoundly ignorant of basic scientific principles and that this needed to change. In 1962, a Cambridge don, FR Leavis, published an ill-tempered response, propelling the issue on to the public stage.

Crick was used as a symbol in the debate: when Snow published an updated version of his essay in 1963, he argued that everyone should understand the structure of DNA and its implications, while Jacob Bronowski dramatised the arguments in The Abacus and the Rose, a radio drama featuring a high-ranking civil servant who represented Snow, a spiky Leavis character, and a scientist modelled on Crick.

In his 50s, Crick used LSD and became fascinated by Michael McClure’s psychedelic poetry

In his 50s, Crick used LSD and became fascinated by Michael McClure’s psychedelic poetry

As to Crick’s views on the issue, he complained to Snow in a 1963 letter: “Can it be really said that any modern imaginative writing has been influenced by Darwin? Is any thought given in literary articles to the fact that while being men we are also mammals? … A naive person might think that novelists would be fascinated by studies of animal behaviour, but if they are I have seen little sign of it.”

(He does not mention William Golding’s 1954 novel The Lord of the Flies, which might be seen as a counter-example.)

Crick expected that scientific knowledge – particularly future work on the brain – would rapidly “make the old culture completely bankrupt”. In 1968 he predicted that by educating children about modern science, “a new ethical system” would soon emerge.

By the early 1970s, Crick stopped discussing such matters, even in private. This was partly prompted by his inability to respond even to mild criticisms of his Edwardian eugenicist views, which were focused on class, or to his belief in a link between race and IQ. He was not interested in politics (he claimed never to have voted) and, when challenged by friends, admitted that he was in a “total state of confusion” about how changes occur in society.

That Crick’s otherwise penetrating mind never challenged his old prejudices and could not master political issues highlights that he was not a flawless hero nor – no matter what graffiti in 1960s Cambridge proclaimed – a candidate for the post of God. Instead, he was an extraordinarily clever man with limits to his interests and perception.

Crick’s withdrawal from cultural debates coincided with a series of shifts in his world. He and Odile moved from Cambridge to California, where he worked on neuroscience and consciousness at the Salk Institute in San Diego.

In his 50s, Crick used LSD and cannabis and became fascinated by Michael McClure’s materialist psychedelic poetry, which he admired for what he described as its fury and imagery and for its open embrace of biology: “When a man does not admit that he is an animal, he is less than an animal,” proclaimed McClure. Crick’s friendship with McClure ran through the second half of his life, and he did not see it as being in contradiction with his scientific views.

McClure’s poems described the numinous and ecstatic psychedelic experience; Crick sensed something similar when he glimpsed the outline of an answer in a fog of data. As Crick wrote to McClure: “I find I am beginning to live in your image world. Almost to dream your dreams.” That could be a line from a Grateful Dead song.

Openly embracing a poetic appreciation of the world is rare in a scientist, but it was an essential part of how Crick thought. He found McClure’s poetic fusion of science and emotion thrilling, as it echoed his own view of the universe and our place within it.

As Crick wrote: “The worlds in which I myself live, the private world of personal reactions, the biological world (animals and plants and even bacteria chase each other through the poems), the world of the atom and molecule, the stars and the galaxies, are all there; and in between, above and below, stands man, the howling mammal, contrived out of ‘meat’ by chance and necessity.”

In 2004, on the day that Crick died after a long illness, McClure completed what he described as his finest poem, dedicated to Crick. Full of the muscular sensation and vivid imagery that Crick appreciated, one stanza seems to represent McClure’s attempt to grapple with his friend’s inevitable end:

PERHAPS WE RETURN TO A POOL

– STEADY AND SOLID;

ready and already completed in fireworks

and lives and non-lives – thin and faint

as powerful odours stirring

my moment’s soul in the mind of place.

Crick would have appreciated the imagery and the emotion. His scientific thinking was not strictly logical, but full of fun and sudden glimpses of something that was previously hidden. In his approach to science, there was poetry – the rollercoaster ride of intuition and perception. For Crick, the two cultures were not separate, but fused in his work, life and thought.

Crick by Matthew Cobb is published by Profile (£30). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £27. Delivery charges may apply

Photography by Alamy