When you walk into Haidee Becker’s London house on a wintery morning you will be greeted by Lobos, a tall dignified dog, be handed a mug of thick coffee and then guided towards a window-lined breakfast nook to eat a bowl of muesli with grated apple and sesame seeds (“for calcium”) and then a plate of scrambled eggs with toasted sourdough. You will intend to have two or three of the Viennese biscuits that wait on the counter, along with a slice of what looks like ginger cake, but you will forget because by then you will be so invested in the life, home and work of this 75-year-old artist, so engaged in conversation about death, family, painting, and also, quite full, that you’ll only remember them on the bus home.

Becker was born in Hollywood in 1950 to a gallerist father and an artist mother, who moved her to Rome at the age of two, then London in 1969. A book her parents made together, New Feathers for the Old Goose, contains an illustrated poem called “How to Make a Fish” that her chef son still repeats. Her mother was an eternal optimist. “At her eulogy,” after she died aged 102, “I said that she was the only person I knew who could read a newspaper from beginning to end, then put it down and say, ‘Isn’t this a wonderful world?’”

Becker is shuffling eggs in a pan – she’s wearing a cropped, darned jumper over soft dungarees, and a blue ribbon in her ponytail. “My mother was the light side,” she says. “And I became her shadow, the dark side. I paint about death.”

Blooms with a view: in the garden with Lobos

Becker became an artist by teaching herself to draw, copying pictures in the National Gallery. Her subjects are often fish, or flowers, “things that are transitory. There are minutes or seconds in which they’re so beautiful, I have to catch them. I love life, of course, but the shadow of death is always with me.”

She had two children, Rachel and Jacob (now the chef-patron of Bocca de Lupo) and, at 46, moved in with the writer Clive Sinclair. She took various spaces as her painting studio, 10 over 10 years, including, for a while, a brothel opposite her son’s restaurant in Soho. She’d raid their fridges for fish to paint, and invite people off the street to sit for her, including (after admiring his unusual eyes as he passed her window) the actor Mark Rylance.

On the first day of lockdown, grieving Sinclair’s recent death, Becker moved into this Bauhaus-inspired home in northeast London with Lobos, attracted by the lateral space. “I came here because I needed a studio, not a place to live.”

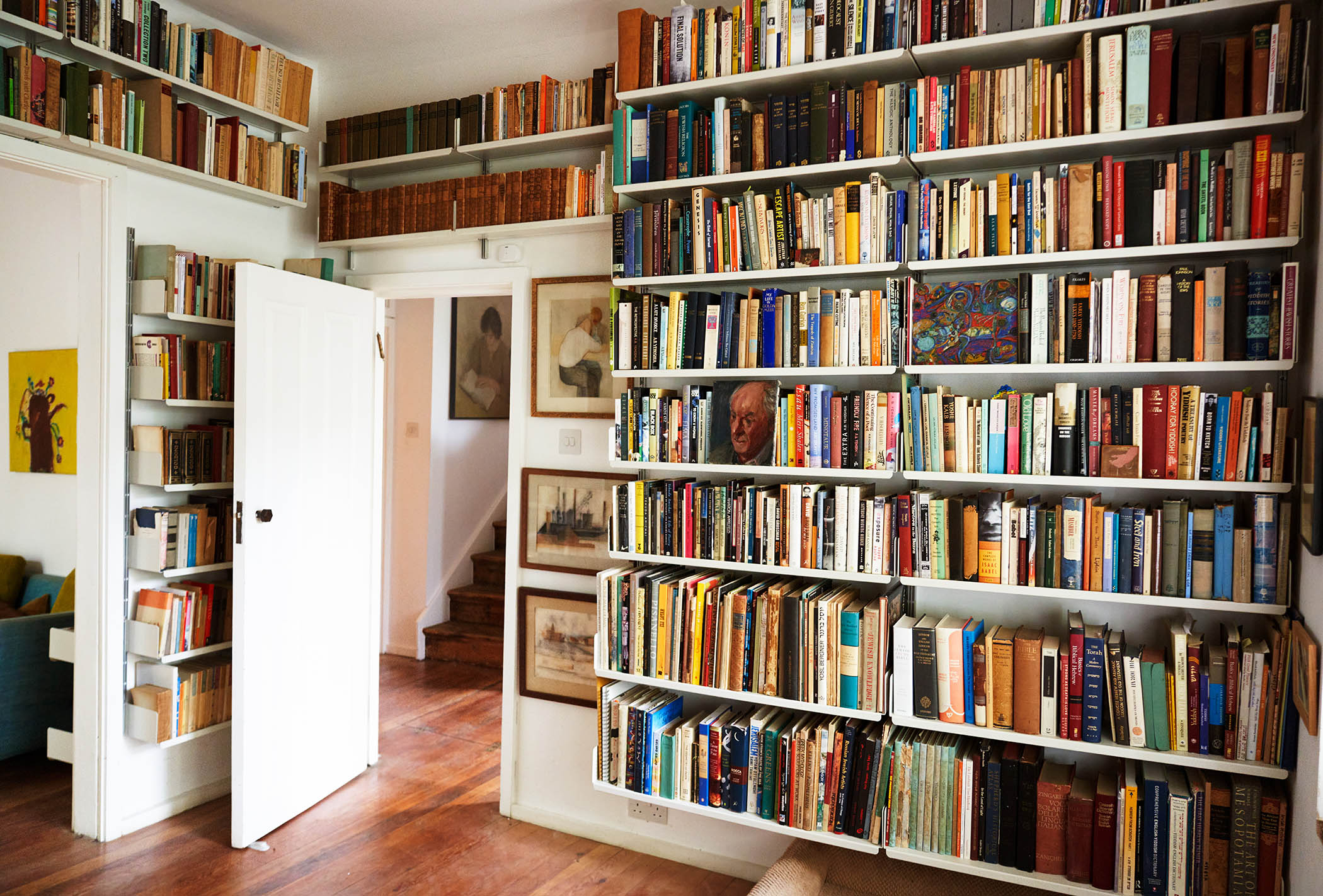

Shelf life: books line many of the walls

She ripped out two bedrooms upstairs and turned the first floor into a workspace, bookended by a small square bedroom and plant-strung bathroom. Paintings are stacked on shelves up near the roof, and on a special wooden mezzanine, and against easels. On the wall is a portrait of an artist friend, down there a portrait of a man she met at a homeless shelter. “People sit down and they talk. They know that they’re opening their souls up. And for me, it’s a quest – it’s almost the same when I’m painting flowers. It’s reaching out and capturing that moment of being alive together. And the thing in the middle,” she gestures theatrically with her sleeves rolled up, “is like a sieve where you catch bits of the other.”

Here is a table strewn with shells and dried flowers and objects once painted, underneath one of many windows. “I have a lot of light in the studio now, 11 sources,” which is too many, it turns out, for someone who needs shadows.

Related articles:

On the wall above her bed is a single tiny portrait by Becker of her daughter, and on the bedside table a painting of a sleeping child by her mother. The two seem to be in conversation. Is Becker working on anything at the moment? “I’m working on everything,” she says.

Small joys: one of Haidee Becker’s flower paintings with a plate of shells

Downstairs, the hallway is a workspace, hung with a mammoth roll of bubble wrap, where Becker presents you with the coffee and stretches canvases and wraps them for storage and presses books into your hand before you leave. A folding room divider painted by her son when he was eight shields the staircase. “Isn’t it magnificent,” she says.

One door leads to the kitchen, with its curved, comfortable nook and, by windows on to a narrow garden, her son’s bonsai trees, which she’s babysitting for a while. The fridge is panelled with her daughter’s lino prints. The other door opens on to a sitting room lined with books, and her huge painting of delphiniums. On the desk more books sit open beside a framed photograph of Sinclair. “This is where I study Yiddish, and try and face the problems of daily bills.” Elsewhere, today’s New York Times, the contents of which inspire in Becker, unlike her mother, impossible despair.

Upon moving into the house, she built two new windows on either side of the fireplace, in which sits a stove that she had made ecologically sound, at great expense, and to their left a glass door leads to a tiny wooden house in the garden, where she has sleepovers with her grandson on Friday nights. The pathway is fairylike and artfully overgrown.

Let the light in: new windows in the sitting room on either side of the fire place

Making a home, she says, back in the kitchen, “is like making a painting. It’s a question of balance.” On the table is a scented bouquet of geranium leaves and spindles of rosemary – small bronze sculptures recline on window ledges and children’s drawings are framed beside the sink. The light here is creamy and soft, the smell of bread, the waiting biscuits. Amid all this calm and textured beauty she’s dismissive of the idea that a person might stand back and design a space to live in, that they might be able to describe their aesthetic.

“It’s a constant. It’s part of my blood, you know, part of my spit.” You want to believe in Becker’s dark side, but in a house this bright and warm, you really need to squint.

For information go to patrickbourne.com

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy