On 9 November 1944, on the sixth anniversary of Kristallnacht, a young American soldier called Henry Kissinger walked across the border into Nazi Germany, wearing the uniform of a foreign army in a land he had once called home. At the age of just 21, he was not even a quarter into the most remarkable of lives that ranged from the destruction of Europe to the rise of AI.

Nine years previously, his father, Louis, had been fired from his teaching position in Bavaria, following the introduction of the Nuremberg laws. By August 1938, his mother, Paula, decided that it was time for the family to flee to America. They stopped briefly in London, before settling, with barely a dollar to their name, in a German Jewish neighbourhood of Manhattan nicknamed the “Fourth Reich”. Thirty-five years later, Dr Kissinger was sworn in as US secretary of state with his proud mother – who never moved away from the family’s small apartment in New York – looking on.

Kissinger’s story could have been very different. Thirteen of his close relatives were exterminated in the Holocaust. There was nothing inevitable about his own path as he sought to assimilate in America as a teenager, changing his name from Heinz to Henry and developing a love of baseball. Perhaps the most significant nod to his European childhood was his lifelong passion for football, which prompted him to visit the Chelsea dressing room on an official trip to London in 1976.

A genuine polymath, Kissinger seemed set for a career in accountancy, before he was mobilised into the US army in 1943. As he arrived for training at Camp Croft base in South Carolina, he was granted American citizenship. It was as a member of the 84th Infantry division that he was present in Germany as the Nazi regime fell. On 10 April 1945, 20 days before Hitler’s suicide, he took part in the liberation of a concentration camp at Ahlem, confronting harrowing sights that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Mentored by another German émigré – the eccentric monocle-wearing, cane-wielding Fritz Kraemer – Kissinger spent the next two years in Germany working on de-Nazification, with no hint of anything other than civility to the people with whom he dealt. Beyond his erudition and raw intelligence, Kraemer thought Kissinger’s unique gift was that he was “musically attuned to history”. But when they fell out in later life over Kissinger’s realist approach to the US seeking accommodation with the Soviet Union, Kraemer suggested – in words that stung – that the long tail of trauma caused by the Nazis had distorted Kissinger’s ethical code by making him yearn for order, stability and social acceptance.

In May 2023, as part of celebrations for his 100th birthday, Dr Kissinger returned to his home town in Fürth, where he was given a warm welcome. In the intervening eight decades, he had lived a truly world-historical life as arguably the most renowned and controversial archetype of the scholar-practitioner since Niccolò Machiavelli, though the appellation “machiavellian” is far too lazily used when describing his career.

Do we need yet another book on Kissinger, particularly after Niall Ferguson’s comprehensive first volume of his life and with part two close to completion? The author of this one, Jérémie Gallon, is eager to point out that he is not a trained historian or academic but a lawyer, diplomat and foreign policy thinker. While his short book does not break new scholarly ground, Gallon is surely right that Kissinger’s was a life so rich in lessons for statecraft that further exploration is almost always justified.

Kissinger’s intellectual formation is a story in its own right. On demobilisation from the army in 1947, he enrolled at Harvard where he produced his undergraduate thesis The Meaning of History, based on a study of Oswald Spengler, Arnold Toynbee and Immanuel Kant. Submitted in 1950 and running to nearly 400 pages, it was so long that Harvard introduced the “Kissinger rule” that no subsequent dissertation could exceed 150 pages. There followed a doctoral study of the Congress of Vienna and a breakthrough work on nuclear weapons that won him wider acclaim. Alongside his academic career, he established himself as a man about town and trusted adviser to the Republican businessman and politician Nelson Rockefeller.

Related articles:

It was as Richard Nixon’s national security adviser (from 1969) and secretary of state (from 1973) that Kissinger rose to something approaching rock star status in the diplomatic world. Such was his allure that, after winning the Nobel peace prize in 1973, he even gained access to the top table in Hollywood, an opportunity he took with some relish. It was Kissinger who quipped that power was the greatest aphrodisiac. Having divorced his German first wife Anneliese Fleischer in 1964, on 30 March 1974 he married the glamorous Nancy Maginnes, the love of his life (although the morning of their wedding was taken up by a meeting at the White House with the Israeli military leader Moshe Dayan).

Kissinger’s feats of cold war diplomacy changed the course of global history. They were based on a highly personal style and the building of rapport in which he was a central actor, though he was careful not to diminish Nixon’s role as some sort of unsophisticated receptacle for his ideas. His achievements ranged from the US-Soviet Union Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty to the Paris Peace Accords that ended the Vietnam War, the opening up of relations with China to the ending of the Yom Kippur war.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Kissinger’s approach required great secrecy. Spare a thought for the Daily Telegraph reporter who phoned in the scoop of the century, having spotted Kissinger secretly going to Beijing to meet Zhou Enlai via Islamabad – only to be scolded by his editor for drinking too much.

For all the cloak and daggers, Kissinger viewed this shuttle diplomacy as part of a historical mission: the pursuit of a more stable international equilibrium and the avoidance of nuclear war. In no way was this simple realpolitik – a worldview caricatured as amoral, in a term oft-used but little understood. But the ethical controversies and trade-offs for this level of grand strategic enterprise were immense. The charge list is well known: the bombing of Cambodia and Laos, and the strategic choice of acquiescence, or indeed active support, for coups, brutal dictatorships and violent aggression in countries such as Pakistan, Chile and Indonesia.

Within America, both the left and right – from Noam Chomsky to Ronald Reagan – thought Kissinger too ready to compromise on human rights for the sake of better relations with Moscow or Beijing. For Kissinger, the national interest came above a universalist view of rights. “The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy,” he told Nixon when under pressure to elevate this issue over nuclear arms control. “And if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.”

Jarring as this is, Gallon’s essential point is that Europe still has much to learn from one of its most famous émigrés, particularly as we enter a more turbulent time in world affairs. The author’s previous book was about his time as an EU diplomat in Washington during Trump’s first presidential term. This offering is of a particular style, comparable to the work of French foreign policy intellectuals like Régis Debray or Raymond Aron. Indeed, the latter gets a chapter here, including a fascinating correspondence with Kissinger. “When we were both professors, we discussed the difficulties of marking out the boundaries between realism and cynicism,” Aron chided his old friend in 1974, suggesting Kissinger had fallen foul of the distinction.

Gallon grasps the vital role of historical perspective in almost everything Kissinger did

Gallon grasps the vital role of historical perspective in almost everything Kissinger did

Inevitably, in a breezier portrait of this kind, there are a few imperfections and debatable interpretations, such as on the long-term effect of the effort to ease cold war tensions in the Helsinki Accords of 1975, or what Kissinger really thought about the weaknesses as well as strengths of Bismarck. Nonetheless, Gallon grasps the vital role of historical perspective in almost everything Kissinger did. He captures well the essence of Kissinger’s approach, which was to see foreign policy as a constructive and creative effort rather than simply a transactional or instrumental business. This in turn was the basis of the close relationships that Kissinger was able to build with interlocutors like Zhou Enlai of China, Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore and Anwar Sadat of Egypt. Gallon also identifies one of the most important but lesser understood aspects of Kissinger: he was known for secret diplomatic missions and backstairs intrigue, but a great part of his life’s work was actually dedicated to public education and ethical reasoning about statecraft and world affairs.

Refreshingly, the book resists the European habit of blaming the current state of world affairs on America alone. On the contrary, it is a plea for Europe to get a grip on foreign policy and to learn from the Kissingerian style – and indeed to relearn the history of European diplomacy that Kissinger so well understood. To make the necessary leap, warns Gallon, Europe will also have to escape a foreign policy based on ethical homilies and the avoidance of hard choices. “As we painfully move on from being the agents of history to being mere bystanders to the world as it evolves around us, we no longer wish to make the difficult decisions incumbent on a great power,” he writes, with a sense of exasperation.

Gallon hopes that this can be done at EU level, but most of the heroes of his book – not only Kissinger but Charles de Gaulle and arguably even Emmanuel Macron – never believed that such feats could be achieved as part of a supranational approach. Where are the Richelieus, Metternichs, Castlereaghs, Bismarcks and Kissingers “who could mould Europe into a 21st-century power” asks Gallon. The answer, I’m afraid, is probably not in the EU diplomatic service, all-too-glaringly absent from the ongoing negotiations over the future of Ukraine.

The book ends with a charming account of Gallon’s visit to speak to Kissinger at his home in Connecticut, having sent him an advance copy of his manuscript. Those who have spent time in Kissinger’s company will recognise the pattern of the conversation, combining seductive personal charm and probing for deeper insight, that Gallon describes. Towards the end of his life, Kissinger was increasingly of the view that one of the sources of crisis in the present world order was the fact that Europe seemed unable, or unwilling, to play its role. Thus, he praises Gallon’s mission but wonders if it is too big a task. “You have no time to lose,” he encourages his young guest as he leaves. But not before the ice pick is delivered: “History teaches us that it has always been hard to influence world affairs without defensive capabilities worthy of the name.”

Kissinger and Kissingerisms continue to frame our world. He had a vision for US-China relations based upon “co-evolution”, a concept that runs contrary to today’s fashion for wild oscillations in policy, but may nevertheless be a feature of President Trump’s visit to Xi Jinping in China in the spring. Some claim, rather unconvincingly, that the US administration’s courting of Russia and desire to bring about peace in Ukraine are part of a “reverse Kissinger”, peeling off Moscow from Beijing to give it a decisive advantage in Cold War 2.0.

The danger for Europe – underscored by the recent US national security strategy – is that the fate of the European continent gets decided in rooms in which European leaders are only present, at best, at the discretion of others.

In the current turbulence in transatlantic relations, one is reminded of Kissinger’s influential 1969 essay on the strains in the western alliance. Expressing some sympathy for De Gaulle, he wrote: “We have shown little understanding for the concerns of some of our European allies that their survival should depend entirely on decisions made 3,000 miles away.” Whose fault is it that Kissinger’s contention is even truer now than it was half a century ago?

Henry Kissinger: An Intimate Portrait of the Master of Realpolitik by Jérémie Gallon, translated by Roland Glasser, is published by Profile (£22). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £19.80. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism.

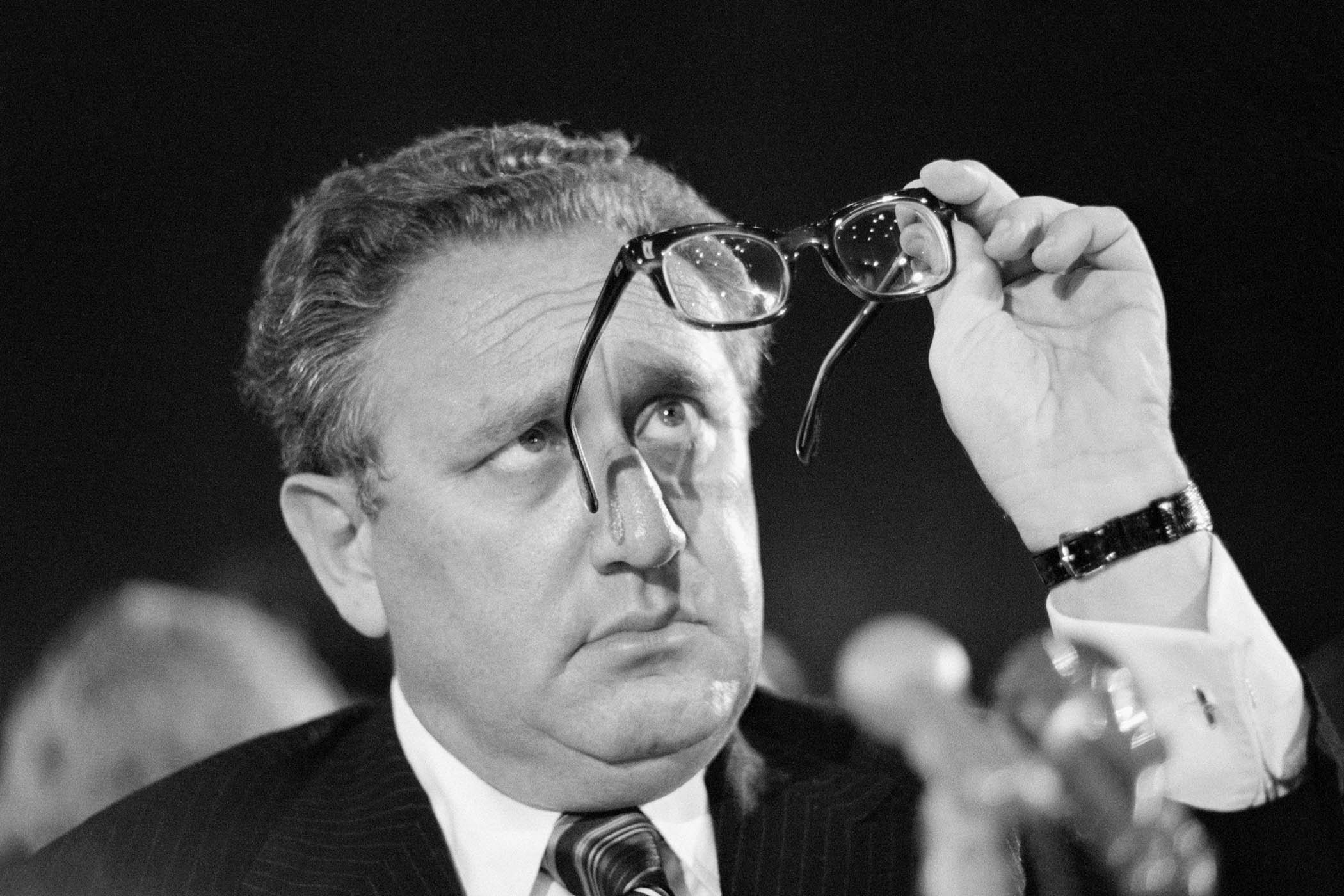

Photography by Bettmann Archive