“Today is Martin Luther King Day,” Donald Trump informed guests during his second inauguration address a year ago, in Washington DC on 20 January 2025. “We will make his dream come true.” Flanked by some of the world’s wealthiest men, including Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, the president used his speech to outline new priorities. Pledging a “revolution of common sense”, he announced a reversal of “the government policy to socially engineer race and gender into every aspect of public and private life”, in order to forge a “colourblind and merit-based” society. Clapping like besuited seals, the billionaire tech barons signalled a significant volte-face from their companies’ past commitments to DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion).

In the weeks preceding Trump’s return to the White House, Zuckerberg’s Meta – previously seen as a pioneer of Silicon Valley’s inclusion efforts, having set the target that half its workforce by 2024 would come from underrepresented backgrounds – announced an end to its “representation goals”, while Bezos’s Amazon informed staff it was “winding down outdated programmes and materials”. Musk – owner of SpaceX and the richest person on the planet, appointed by the new administration to run the Department of Government Efficiency (albeit briefly) – has used his social media site X to brand diversity schemes “not merely immoral” but “also illegal”, blaming them for everything from air crashes to medical malpractice and failure to tackle wildfires. As corporate America, having woken up to the realities of racism in the Black Lives Matter era, swiftly backtracks, some hold on to Dr King’s hope that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice”.

In her book Was That Racist?, the diversity, equity and inclusion expert Evelyn R Carter promises readers that they can “masterfully navigate conversations about DEI and anti-racism at work”. As “one of the few Black people in the field of social psychology” hosting workshops for American businesses, she contends that “White people and people of colour perceive racial bias in fundamentally different ways”. A “lifelong lover” of research who, embracing her “inner nerd”, confidently cites scientific papers, Carter intertwines workplace anecdotes with insights into her personal life, many from early childhood. One of a small number of non-white faces in class, she first remembers encountering racial discrimination in the playground, aged four, and recalls schoolfriends finding her fortnightly braided hair-washing routine “gross, weird, and wrong”.

As a child, she played the violin (“quite well, in fact”) and like virtuosos dedicated to “early, focused practice”, she wants us to commit to “the continuous, intentional practice of recognising and addressing bias”. Racial bias – distinct from racism, which “uniquely targets people of colour” – is something everyone can be guilty of. Breaking what she describes as a “social taboo”, she states: “I, a Black woman, can (and do) harbour racial biases,” divulging reservations around having “a White woman as my doctor” and confessing to confusing two Asian applicants for a job.

One notable blindspot is Carter’s faith that digital platforms may play a role in fostering racial harmony

One notable blindspot is Carter’s faith that digital platforms may play a role in fostering racial harmony

Systemic racism, which goes beyond individuals and their actions, produces “dramatically different outcomes for “people from different racial groups”. As a concept, it is roundly derided by reactionary forces on either side of the Atlantic, but the racial dynamics of modern America are stark enough that the average white household has almost 10 times more wealth than its black equivalent, which Carter puts down to an “inevitable and cumulative outcome of a system built to privilege White people”. Inequality in the field of healthcare sees racism manifest “long before a patient enters the doctor’s office”, with black people underrepresented in clinical trials and their access to the system limited by their insurance.

She hopes white people can reject the “false comfort” of colour blindness and become more aware of their own racial identity. “Whiteness shapes White people’s lived experience,” Carter argues, “just as profoundly as my Blackness shapes mine.” The failure of successive generations to confront the legacy of historic injustices – from the massacres of Indigenous tribes following the Pilgrims’ arrival in the 17th century through slavery and post-Reconstruction lynchings – is rooted in an eagerness “to tell a redemptive story of America, and of Whiteness”, yet not enough, she says, has been done to earn such redemption. With people of colour tired of “shouldering the responsibility” to combat racism, the author wishes for her white peers to acknowledge their “unfair advantages” and “learn to exist in spaces where Whiteness is not the racial default”.

Drawn from professional experience, the advice Carter proffers is well meaning (“find people modelling the behaviours you want to emulate”; “learn from your mistakes and track your progress”), though occasionally descends into therapy speak (“I see you and celebrate you for what you’ve done”). Borrowing jargon from American management theory, the author’s frequent use of wonkish terminology (“growth mindset”, “mentorship gap”, “talent pipeline”) fails to translate into other settings. Her pop cultural case studies, from Serena Williams to sorority dance competitions, pique the reader’s interest, but she becomes unmoored on leaving American shores, exaggerating the impact of symbolic safety pins worn to display an opposition to Brexit, which she believes was “adopted by a mass protest movement” in Britain.

One notable blindspot is her faith that digital platforms may play a role in fostering racial harmony. Having “spoken with many a startup founder” and addressing audiences of “C-Suite leaders” at technology conferences, Carter is savvy enough to know the industry’s post-BLM DEI policies were only created to “positively impact their bottom line” or avoid flak on social media. Yet, her belief that commenting on a discriminatory Facebook post (even if “it takes the better part of your evening”) is “preferable to silence” or that algorithms help social network users gain diverse perspectives is naive at best. Social media – which favours intemperate and polarising opinion – is a primary global driver of racism in the digital age. Musk seems intent on fanning the flames, appearing via videolink with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) on the campaign trail or broadcasting to Tommy Robinson’s Unite the Kingdom rally in London. At a time when nativists can guide government policy, confidently taking to the streets while saturating the online sphere with supremacist slop, we might need to rethink the value of sharing inspirational civil rights primers at the “anti-racist book club”.

Related articles:

Showing the limitations of corporate DEI (and, before it, “affirmative action”) in advancing the cause of black liberation, this self-help book is unlikely to make you less of a racist in the same way that meaningful social change won’t start in a workplace seminar – especially if your boss is Big Tech in Trump’s America.

Was That Racist?: How to Detect, Interrupt and Unlearn Bias in Everyday Life by Dr Evelyn R Carter is published by Robinson (£22). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £19.80. Delivery charges may apply

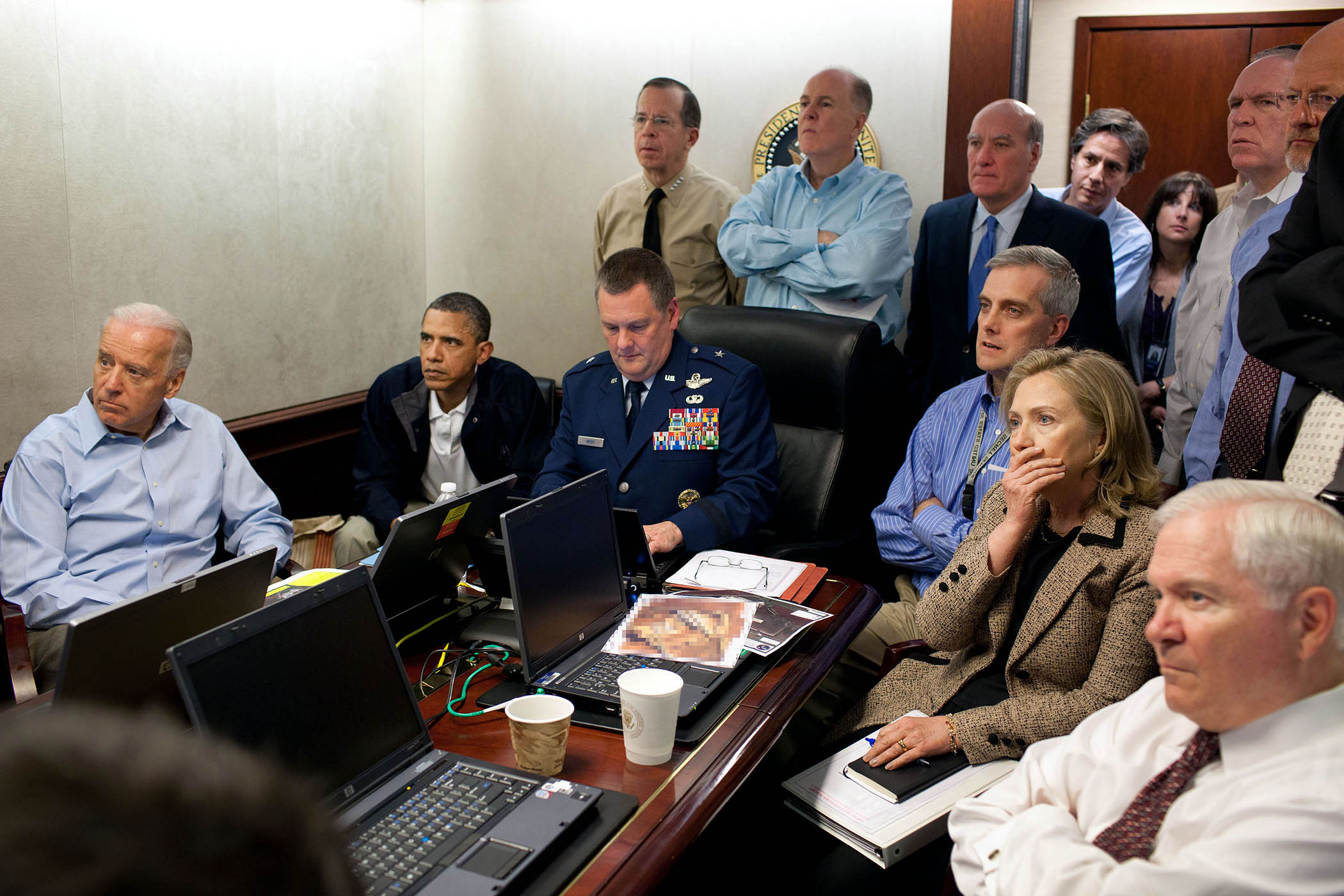

Photograph of President Trump visiting the Martin Luther King Jr Memorial in January 2019 by Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy