How the woodland centre Jacob’s Pillow became a crucible for modern dance – and an artistic retreat from Trump’s America

There are bears in the woods that surround the town of Becket, Massachusetts. There are also dancers. A “beware people’” crossing sign wears a pasted-on tutu, to warn of their approach.

Jacob’s Pillow is America’s longest-running international dance festival, held every summer in a collection of wood cabins, barns, studios and stages up a winding road in the midst of a forest.

Founded in 1933 by the American modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn, it retains a sense of magic. It’s a place of retreat, where dancers come from across the world to perform, to experiment, to entice. It exists on a tightrope of contrasts: historic and modern, traditional and experimental, rural and metropolitan. It also represents the liberal arts establishment at a time when Donald Trump has declared war on everything it stands for.

All of this essential idiosyncrasy was on full display at the beginning of this year’s festival – the 93rd – when it opened a new state-of-the-art theatre designed by Netherlands-based architects Mecanoo. “Those tensions of things coming together are what gives Jacob’s Pillow its power today,” says archivist and director of preservation Norton Owen, who first came to the Pillow, as it is known, as a dancer in 1976. “It’s the new within the old, the advanced within the primitive. It’s both things together that really make it unique.”

Shawn was a world-famous dance star when he came upon the farm. It was named by its 18th-century owners, who associated the large rock in its grounds with the pillow on which the biblical Jacob laid his head when he had his dream about a ladder up to heaven. It had no running water or electricity, but one of Shawn’s first acts was to lay a maple floor in a barn to use as a studio for his newly formed company of male dancers. Local people began to drive up the hill, parking their Ford Model Ts outside the barn door, to watch. The idea of a dance festival was born.

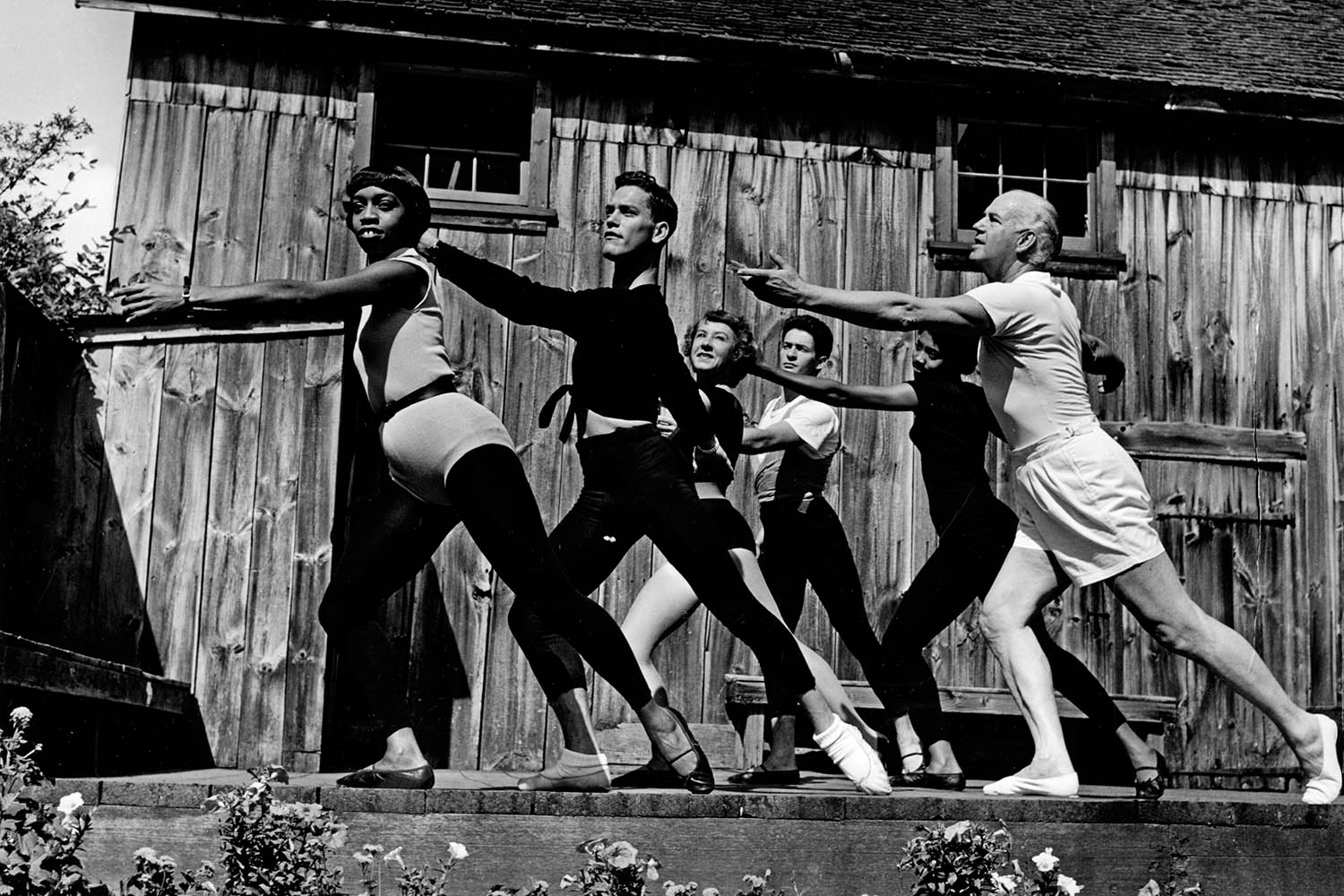

Pioneer of modern dance Ted Shawn (far right) leads a class in 1954

Shawn welcomed both contemporary and balletic figures to perform in his carefully devised mixed programmes, as well as Indigenous artists. Early bills featured Britain’s Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin, and Asadata Dafora from Sierra Leone, choreographer of Orson Welles’s 1936 all-black Macbeth. The English ballerina Margot Fonteyn appeared there, so did a young Twyla Tharp. The place became a crucible for the development of modern American dance: Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Merce Cunningham, Alvin Ailey, Mark Morris and more recently Kyle Abraham and Pam Tanowitz have all had work performed on its stages.

As the years passed, the Pillow underwent many configurations and changes, facing financial disaster and uncertainty on multiple occasions but always, under wise guidance, somehow surviving and thriving. Over the years, it acquired a more professional sheen and three performance spaces: the Ted Shawn theatre, the first stage created specifically for dance in the US, built in 1942 by Joseph Franz; an open-air stage with soaring views of the Berkshire mountains (opened up in typically pragmatic fashion by the installation of a septic tank); and the Doris Duke theatre, a smaller space for intimate works and experiment.

In November 2020, the original Doris Duke burned down, with firefighters from six towns narrowly stopping the fire spreading to the wooden structures nearby. Those volunteers were guests of honour at this month’s unveiling – on time and on budget – of the new Doris Duke theatre, a $30m, 20,000 sq ft building whose ridged pine exterior blends beautifully with the older structures around it, with interior technology that propels the Pillow into the 21st century and beyond.

The new Doris Duke theatre clad in pine

The opening gala featured a piece from British choreographer Alexander Whitley, uniting two dancers on different stages in a digital duet of ebb and flow, while an exhibition explored the possibilities of AI and livestreaming. But the new Doris Duke is also bound strongly into the past and into the land. “I always said, it’s not a theatre in Brooklyn,” says creative director Francine Houben. What she describes as “a magical wooden box” is built on land native to the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans, now based in Wisconsin, and a condition of the building was that an Indigenous artist should be part of the design team.

Mecanoo worked with Jeffrey Gibson to produce a building that incorporates Indigenous spatial principles, opening up to all four points of the compass, with sliding glass doors offering green vistas of the woods and fields around. Its surface, with seven strata of textured vertical graining, embodies a belief of stewardship for seven generations ahead.

The weekend was marked not only by dance but by the opening of a garden and fire pit to one side of the building that contains a powwow circle, traditional medicinal plants and the Mohican “Many Trails” symbol of resilience and endurance. The celebration, with drumming and song, went beyond tokenism for Kathi Arnold, one of the garden designers. “It’s just pure recognition and respect,” she says.

In this inclusive atmosphere, as in so many things, Jacob’s Pillow feels at odds with much of Trump’s America. It has already lost some funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and other federal bodies. Executive and artistic director Pamela Tatge is confident that, by increasing revenue streams and fundraising, Jacob’s Pillow will survive. But she recognises the team are operating in a difficult environment. “It’s an assault on what we know and love,” she says. “But it also feels like kindness is the best resistance … I truly believe in the power of art to bring people together.”

Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, Massachusetts, US, runs until 24 August

Photographs by Jamie Kraus/Getty Images/Iwan Baan