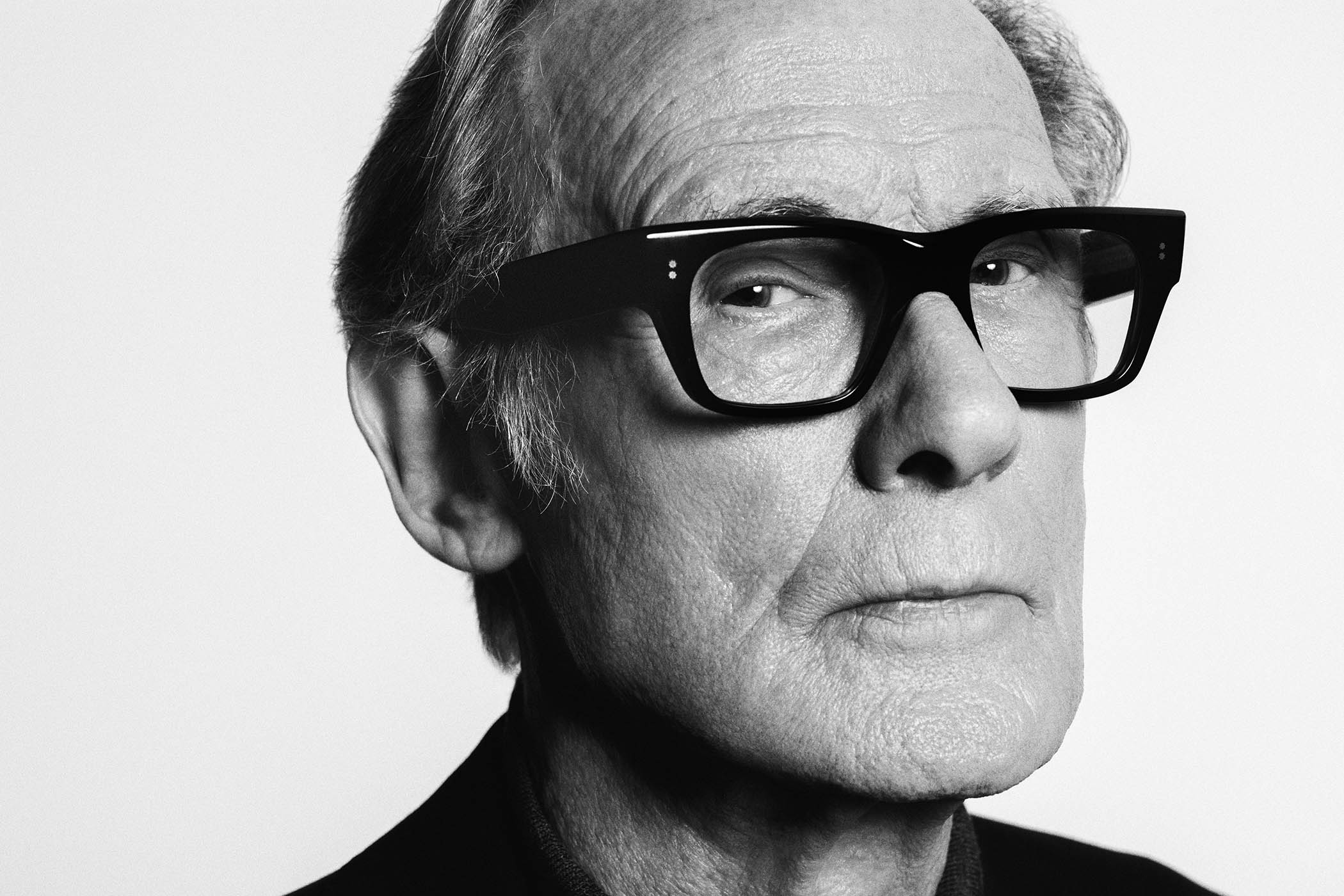

The writer of Adolescence on his new phone-hacking drama, living with disability and why he feels a responsibility to tell stories that matter

Photograph by Andy Hall

According to Jack Thorne, British TV is in trouble. “There’s a conservatism creeping in all over the place,” the writer of Adolescence says of a cash-strapped industry increasingly forced to seek international funding. “Shows specifically about the UK are very difficult to get made. The future great tellers of socially realistic stories about our country are being pushed towards: ‘Can it have a dead body in it?’ ‘Can it have a weary detective in it?’”

As it happens, Thorne’s new drama, The Hack, does have a dead body and a weary detective – although this knotty, grownup take on the phone-hacking scandal is far from the infinitely scrollable content that fills streaming platforms. The seven-part series centres on the journalist Nick Davies (a winningly fourth-wall-breaking David Tennant) and his efforts, overseen by the then Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger (Toby Jones), to uncover the full scale of reporters’ criminality at the Rupert Murdoch-owned tabloid News of the World.

Alongside this narrative unfolds the story of the still unsolved murder of the private investigator Daniel Morgan, by an axe to the head, in a pub car park in south London in 1987. The Metropolitan police’s Detective Chief Superintendent Dave Cook (Robert Carlyle) is the central link in the chain between the two stories.

Thorne and I are talking in a boardroom at Bafta’s London headquarters, all 6ft 6in of him perched on the edge of his seat as he holds eye contact and speaks intently – his words occasionally running ahead of his thoughts and into a pattern of “you know”s, like a bus being forced to wait to regulate the service.

When Thorne was approached about The Hack, his initial reaction was: “‘Oh no, I know this story.’ And then I read on and thought: ‘Oh, I don’t know this story at all.’” What he had first thought would be simply a tale of “journalism behaving badly” was an ever-widening examination of how the powerful – police, politicians and the press – protect their own interests, and how trust in journalism began to erode.

“I grew up with: ‘If it’s on the BBC news, then you trust every word.’ Now everything is contested. I do think what happened here did damage to the tenets of journalism.”

The Hack is state-of-the-nation television of the sort we have come to expect from Thorne, although he has plenty of other modes.

As a West End hit-maker, he wrote Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, seen by more than 11 million people worldwide. As an adapter, he has reimagined Nancy Springer’s Enola Holmes Mysteries series and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy for the screen, as well as Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol for a phenomenally successful annual production at the Old Vic. His 2023 play The Motive and the Cue, about the making of Richard Burton and John Gielgud’s Hamlet, revealed a dramatist in total control of his craft.

David Tennant and Toby Jones in The Hack

It’s the Netflix drama Adolescence, though, that has dominated his year: a few days after we met, it won six Emmys, including an award for Thorne and his co-writer Stephen Graham. When it aired in March, the show gave the debate around social media and toxic masculinity a new articulacy and urgency. Thorne appeared on Question Time and was invited by Keir Starmer to Downing Street. In July, the Online Safety Act brought in age verification for adult content and stipulated that “platforms have a legal duty to protect children online”.

Is Thorne happy with the progress?

“No. There’s so much more to do. Did it shut down pornography? No, it’s really easy to find. Did it shut down those darker forces on the web? No, they’re still very available. Did it do anything to protect our kids? Nothing at all. And [the former technology secretary] Peter Kyle has been promoted.”

Trying to work out how to “use a moment” – to “plant the flag in the ground in the right way” – is something that preoccupies Thorne. He admired and envied Mr Bates vs the Post Office – made by the team behind The Hack – which in 2024 led to a change in the law to quash the false convictions of sub-postmasters. Thorne’s own missed moments haunt him: Best Interests, his 2023 drama starring Michael Sheen and Sharon Horgan as a couple fighting to secure care for their daughter who has a rare form of muscular dystrophy, should, he felt, have sparked a conversation about disability and the NHS.

“You talk to real people who have been through hell – you feel a huge responsibility to represent their story. I was really proud of the show. But could I have found a way of getting inside the story that brought more attention to it? Was it just a matter of bad timing, or was it bad writing? I felt like I let those people down.”

Thorne, 46, is unsparing in holding himself to account. The dauntingly high bar has, perhaps, been there since his own childhood, growing up in Bristol and Newbury, Berkshire, the middle child of four (his older brother and sister are twins), under the eyes of his politically staunch and morally exacting parents.

“We felt pressure,” Thorne has written, “to be significant and to shine out in whatever we did, and if we didn’t, we were expected to try harder next time.” His father was a town planner and president of his union; his mother, a teacher who became a carer for adults with learning difficulties, “went to jail for the CND”.

Adolescence won six Emmys

Thorne was born in 1978, during the winter of discontent. “There’s a picture of us in the newspaper as part of a protest when I was three on my dad’s shoulder,” he says. “I remember eating Welsh cakes at a Welsh coalmine, and I remember: ‘Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, out, out, out!’ We spent a lot of time arguing about politics.”

His mother was a member of the Labour party but left in 1996, outraged by shadow health secretary Harriet Harman’s decision to send her son to a grammar school. A week later, Thorne joined. “They remain much more political than I am, and condemning of me when I make soft choices.”

The other great enthusiasm in the Thorne household was amateur dramatics. “My dad wrote plays, and was quite serious about it. The one I remember was called Motorway Magic, an environmental musical pantomime.” Thorne has a photo of his father as “Aunt Connie, a dame in a dress shaped like a traffic cone,” on the wall of his office.

Until the age of about 10, Thorne was a popular kid. But “by the time I was a teenager, I was on the outside. I was constantly looking at other people and going: ‘I don’t know how to talk to you. And I wish I could, because it seems much more fun talking to you than talking to myself.’” Intent on pushing through his social awkwardness, he set his sights on becoming a politician or an actor.

Then, at the Young Labour conference in 1997, exposed to much political manoeuvring and “whispering”, he discovered “there’s no way I could be a politician”. Cambridge University – where, despite his disillusionment, he read politics – was not much easier. “I was going from a state school, where I was the clever kid, to a place where I was profoundly mediocre. I wasn’t quite ready for it.”

Another dream dissolved when he realised, on stage during a student production of King Lear, that he simply wasn’t good enough. “I was Edgar, and Edmund was played by an actor called Ben Silverstone. And I was in scenes with him where I just thought: ‘You’re what I want to be. And I can’t be you.’” Thorne turned to directing, but quickly discovered the rights to a play cost £65 a night. “I didn’t have that. So I thought: ‘OK, I’ll write one.’ And then as soon as I started writing, I was like: ‘Oh, this is it.’”

Thorne threw himself into writing, finishing 10 plays and staging many of them. “I loved it. But also I was obsessive, I wasn’t sleeping, I was wallowing in anxiety. I was riding a wave that wasn’t very good for me.” The wave crashed down when, aged 21, Thorne was diagnosed with cholinergic urticaria: an extreme allergic reaction to heat. He dropped out of university and came home, where he spent six months in bed, lying flat (even his body movement would provoke a reaction) with the windows open throughout winter.

Some writers find that an illness marks a creative turning point. But for Thorne, “my experience of being ill was feeling like a failure”. He had, he felt, thrown away his chance at being a functional adult. “I was in pain. I went from being in constant movement to complete silence and staticness. And I did write, but it was full of self-pity, and it was rubbish. I really did hate myself.”

In the slow and “intensely lonely” years of recovery (during which he managed to finish his degree), Thorne began to feel he might be disabled. He attended an open day run by Graeae, a theatre company of disabled and neurodivergent artists. Talking to the blind writer Alex Bulmer, Thorne admitted he wasn’t sure if he belonged. He told her his story. “And she said: ‘Of course, you’re a disabled person.’ It was like a weight was lifted. It was that coming-out moment: ‘OK, I’ve got a new identity. All these people understand what I’ve been through.’”

Much later, he was diagnosed as autistic, after a listener to his Desert Island Discs interview wrote in suggesting he get tested. “That was more complicated,” he says. “I’m still figuring it out.”

It would take more than 10 years for the worst effects of his cholinergic urticaria to fade. Thorne’s advocacy for disability rights has since powered shows such as Best Interests and Help – a devastating account of a care home during Covid, with Stephen Graham as a man with early-onset Alzheimer’s – and campaigns to improve disabled access to the TV industry.

A Labour member still, he is “profoundly angry” about Starmer’s approach to welfare. “Pip was a really dark moment,” he says, referring to the cuts to personal independence payments. “Even the watered-down version [of the welfare bill] will cause hardship to a community that’s had to cope with more hardship than any other. That’s what the Tories did for 14 years: they kept cutting the ground from under disability. I don’t understand why the Labour party thinks that’s OK.”

Is Thorne our “national dramatist”? His friend James Graham, three years his junior, described Thorne as his “nemesis”. The writer of Brexit: The Uncivil War and Sherwood on TV, and This House and Dear England for the stage, Graham has become the great contemporary chronicler of British politics.

But if Graham gives shape to our national identity, Thorne is the laureate of our national psyche. He has described television as “an empathy box in the corner of the room”, and in seeking the limits of our empathy, he goes deeper and darker than others dare. In the Operation Yewtree-inspired National Treasure from 2016, the veteran comedian accused of rape (played by Robbie Coltrane) is a shadowy, human tangle of impulses, the drama’s events playing out in an arena where celebrity, memory, justice and prejudice clash and commingle. It seemed to hold a mirror up to Britain – a strange place of catchphrases and inequality – in a way that few other shows manage.

Thorne spent 16 hours a day at his desk while writing for teen drama Skins

Thorne’s productivity is extraordinary. When working on his early plays and writing for the teen drama Skins and Shane Meadows’s This Is England series, he would be at his desk for 16 hours a day, seven days a week. He scaled it back a little in 2014 when he married Rachel Mason, a comedy agent. It took them seven emotionally bruising rounds of IVF before they had their son, Elliott, now nine. (In typical Thorne fashion, the experience led directly to a script: the couple wrote a film, Joy, about the breakthrough that led to the first IVF baby.)

Living in Hampstead, north London, with Mason and Elliott, he is now “slowing down a bit, I hope. Because there’s been too much of me.” Worried about “dominating” the landscape, he wants to make space for other writers, particularly disabled ones.

His idea of slowing down is not everyone’s. Thorne has written a forthcoming TV drama series about Liverpool FC’s rise under Bill Shankly and a film for Meadows. He is also one of three writers on Sam Mendes’s planned Beatles movies. He feels, though, that his career-defining play has so far eluded him. “I have that itch a tiny bit. I’ve done plays that I’m hugely proud of, and plays that I’m deeply emotionally involved in, but I’m still hungry to make something where I feel I’ve got closer to expressing who I am.”

If Thorne’s best work poses complex questions, “who I am” may be the toughest puzzle of all. Although in conversation a bright sense of humour burns through his earnestness, his self-assessment is invariably harsh. He has a tattoo on his right wrist: “be good”, in modest lowercase. It’s a quote from ET: The Extra-Terrestrial, his favourite film, but also a note to self. “I can be lazy, I can be self-indulgent, I can be very selfish. There are times when I really disappoint myself, so I do like to keep that as a reminder.”

The day after our first meeting, Thorne is announced as the new president of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain, the trade union body. We talk on the phone. He does not sound lazy. “We’re about to have the fight of our lives. What’s happening with AI will have profound significance on all of us,” he says. “The creative industries feel critically undervalued by our government.”

The advocate is back, talking of marches, the economy, copyright. “It’s good to be part of that fight,” he says. Thorne is ready for it.

Watch The Hack at 9pm on 24 September on ITV1 and ITVX, where the full series will be available to stream

Photography by ITV, Netflix, Joss Barratt/Channel 4