China is simultaneously the workshop of the world and an economic calamity waiting to happen. It is arguably the most successful autocratic regime on the planet monitoring, controlling and smothering every move of its 1.4 billion inhabitants, yet at the same time one of the most vulnerable and illegitimate. In some areas – notably its commitment to green technologies, reliance on dirt cheap renewable energy and predictability in its approach to international relationships – it is a welcome exemplar and partner. In others, such as cyber hacking, escalating military ambition and aggressive financial colonialism via its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it is an adversary to be feared.

Yet for all the ambiguity, the second-largest economy in the world cannot be ignored. The International Standard Industrial Classification identifies 419 industrial product categories ranging from furniture to computer manufacture; China’s industry minister boasts that because China produces in each of them it has a “comprehensive” industrial chain. President Xi Jinping’s declared ambition is “completion” – or to dominate all 419 product categories and then do the same in science and technology.

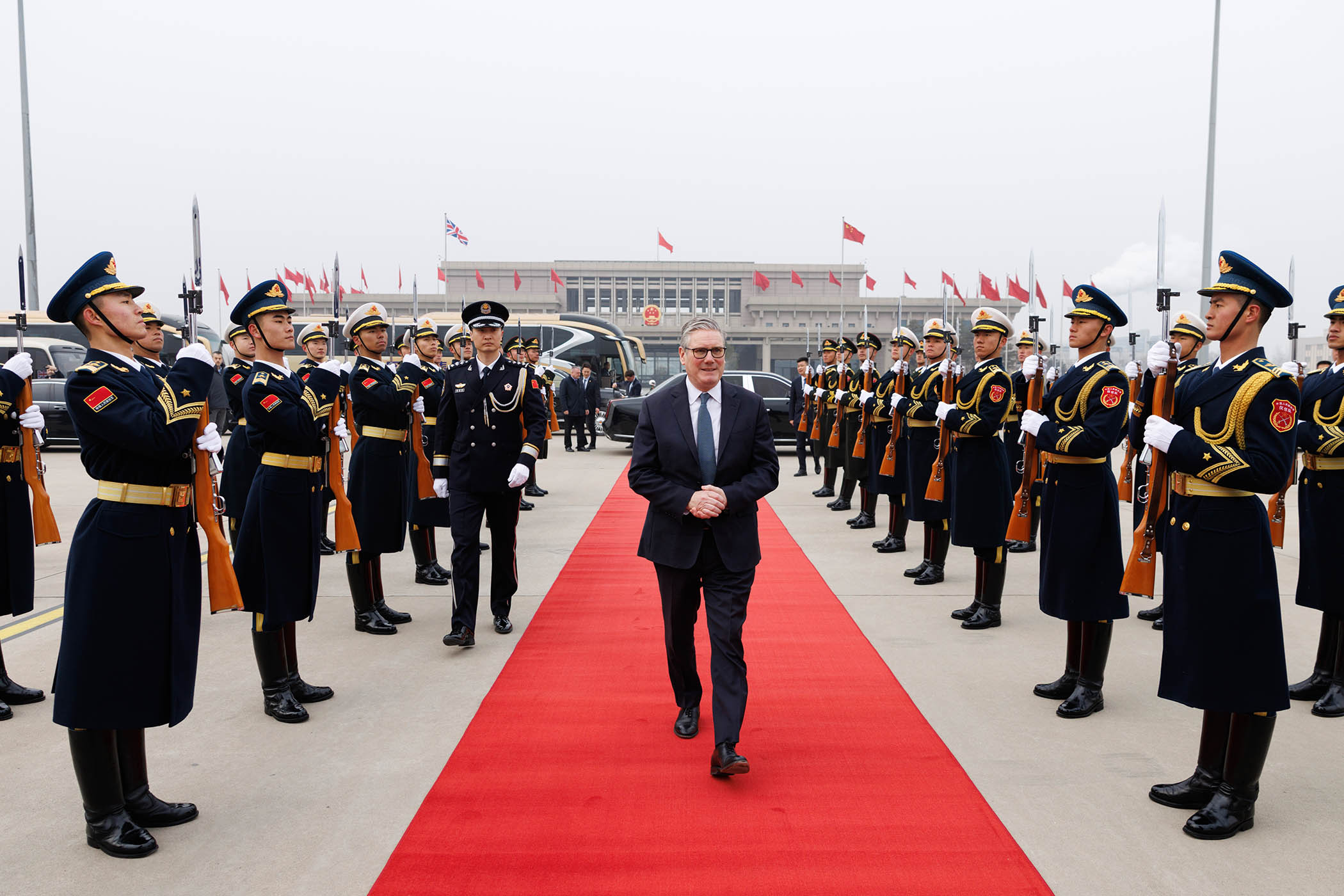

As matters stand, it could. Even if China eventually falls short, to be able to make the claim plausibly is impressive. Today no country can build a 21st century industrial sector without deploying components that are Chinese made, in a crowding out of western industrial capacity that is part of the reason for the widespread slowdown in productivity across the industrialised west. It is an awesome power, allowing China to emerge relatively unscathed in the tariff wars with the US. Yet while Donald Trump may have gone over the top in claiming that Britain’s attempt to create a more sophisticated win-win “strategic” relationship with China – provoked by Keir Starmer’s state visit last week to Beijing – is “dangerous”, real wariness is more than justified.

Even while President Xi was welcoming the thawing of the relationship with Britain, China was assembling a formidable navy in the South China Sea as a reminder to the US that it is all too ready to exploit the vacuum left by the deployment of US naval power to Iran. And note that last year China offered more than $200bn in soft loans under the BRI; more than 150 countries, largely in the global south, are indebted. This is an economic superpower that can count the majority of the world’s countries as client states – a soft 21st century imperialism.

But it is a superpower with chronic weaknesses. If the key to its economic success is its engineering culture and the emphasis on production that follows, as argued by Dan Wang in Breakneck, a book rapidly becoming a must-read on China (and reportedly read by the team around Starmer on the flight to Beijing), that is also a potential foundational flaw. Churchill once said he would rather see finance less proud and industry more content – as true now as it was a hundred years ago – but in China industry is hubristically dominant while finance is the pliant and helpless servant on which the whole system is constructed.

Essentially, China’s economic prowess is built on a volume of never-to-be-repaid bank debt that dwarfs its economy. It is a banking system that, if the losses of trillions of dollars of defunct loans to its industrial corporations were ever crystallised, would be bankrupt. Only the economy’s forward momentum – rather like a bicycle that can never come to a standstill – stops the whole machine from collapsing.

Nor is an Orwellian state’s smothering of all social interaction, and at the limit imprisoning successful entrepreneurs, conducive to innovation. Eighteen months ago, Xi deplored that China’s capacity to produce so-called unicorns – tech companies whose share capital is valued at more than $1bn – seemed to be weakening. The mote is in his own eye, but no colleague is brave enough to tell him. Attacking any source of power other than that dispensed by the party in order to keep control – Xi’s mantra as he enjoys self-appointed lifelong power – necessarily ensures that every Chinese tech founder either aims low or kowtows to the party. Why get arrested for success?

The world wants to investin our scale-ups and be part of an emergent success

The world wants to investin our scale-ups and be part of an emergent success

Here, China is as interested in the UK as the US: it wants to build a super-embassy in London and build relations with the UK for similar reasons to that of Larry Ellison, the second-richest man in the US, who wants to embed himself at the heart of Oxford University’s life science research via the Ellison Institute. Britain’s range of scientific achievements, and its capacity to create a generation of viable businesses from them, is understood by the Chinese Communist party and US venture capitalists alike to be among the best in the world.

Related articles:

Britain has the capacity and entrepreneurial culture to become Europe’s tech superpower, especially if the Labour government could reproduce some of China’s single-minded support for science, technology and production by turbo-charging its still too timid if promising policy programme. The world wants to invest in our scale-ups and be part of an emergent success free of the shadow of either Xi or Trump. So, for example, should our irrationally anti-British pension funds and our even more irrational anti-British rightwing political parties.

More importantly, this is one of the most promising avenues to address the cost of living crisis. For a century until the financial crisis British output per person hour grew on average by 2% per year. Since then, the growth has collapsed, and with it the growth in living standards – the background for so much disaffection and the rise of Reform. Almost no great companies have emerged from all our technological and scientific ventures, instead sold overseas. Too many atrophying monopolies have continued. Too much production has been offshored to China.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Brexit shrank our markets and our trade. Austerity eviscerated vital public investment. All need to be reversed while avoiding China’s epic mistakes. God knows what Starmer and his entourage made of what they witnessed in China. But if they draw the right conclusions, the trip to Beijing could be much more important than tariff concessions on whisky or easier tourist visas. It could be transformative.

Photograph by China Photos/Getty Images