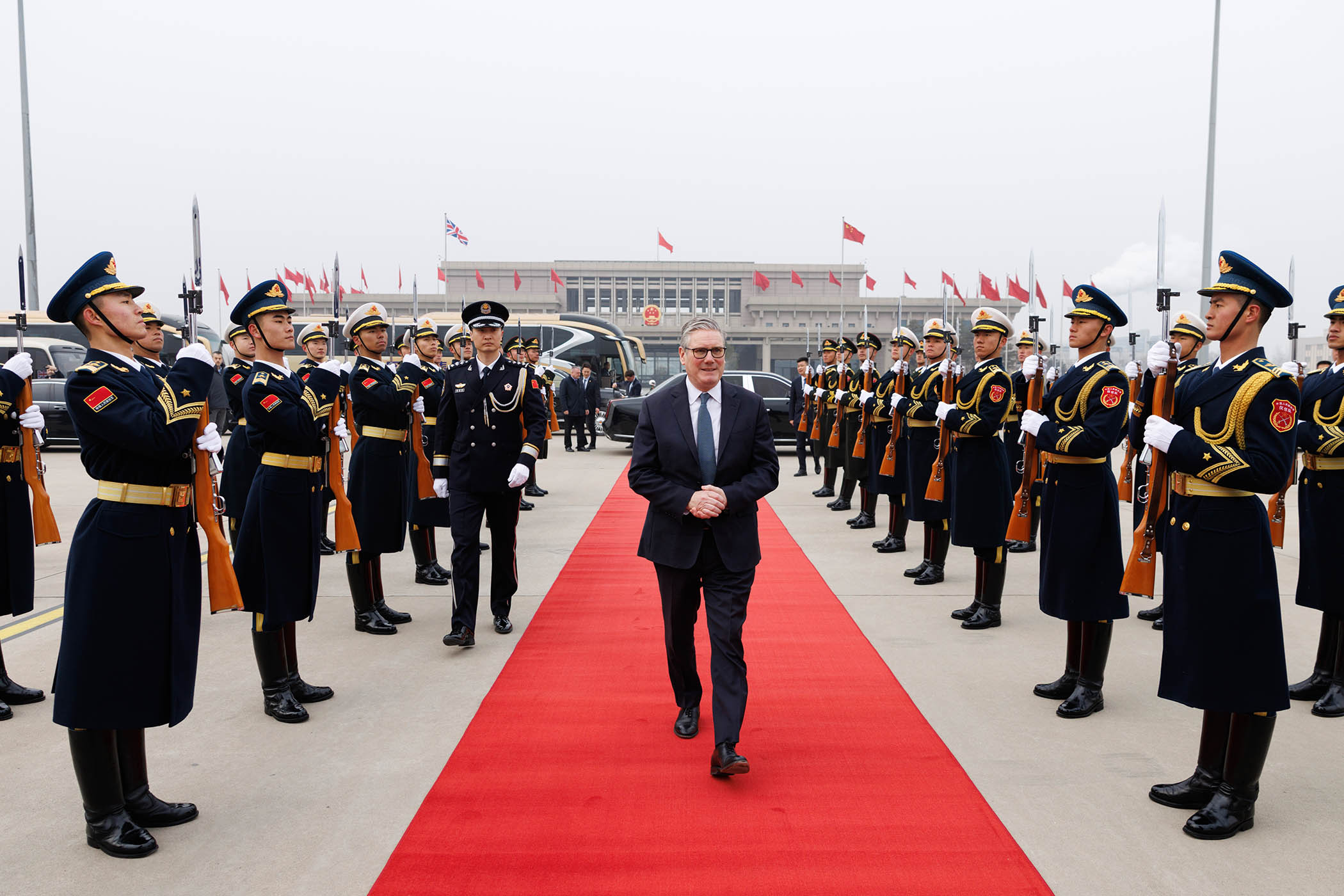

As soon as the television cameras had left the Great Hall of the People at the start of Keir Starmer’s meeting with Xi Jinping in Beijing, the Chinese president turned to the prime minister to start their private talks. But instead of discussing geopolitics or trade deals, he started speaking about his childhood. Xi spent his teenage years living in a rural cave after his father was denounced by Mao Zedong.

“[Xi] spoke about the cultural revolution and how he wanted to read broadly, so he broke the rules and had to walk 10 miles to get the books he wanted,” said Peter Kyle, the business secretary, who was sitting across the table from him. “One of them was the complete works of Shakespeare. He spoke about the importance that English literature had played in his upbringing, and the creative use of language.” Amid the pomp and ceremony, the guards of honour and the diplomatic formalities in Beijing, it was a rare moment of humanity.

Kyle was surprised by the “warmth” of Xi’s unscripted opening remarks before the more structured part of the meeting began. The Chinese leader expressed his admiration for the late Queen and reminisced about going to the Plough pub near Chequers with David Cameron. “Keir said he’d eaten there last weekend,” the business secretary said. “President Xi spoke about the warmth and openness that went with the ‘golden era’ [of UK-China relations] and then what came next. He said: ‘Then of course everything changed, so now we have to talk about what we’re going to have going forward.’”

Starmer ended the meeting pledging to build a “broader, deeper and more sophisticated relationship” with China.

By the time the prime minister flew out of Shanghai bound for Tokyo yesterday, the Chinese sanctions on UK parliamentarians – including Iain Duncan Smith, accused of spreading “lies and disinformation” about human rights abuses – had been lifted. Starmer had secured a reduction in whisky tariffs and the prospect of visa-free travel for Britons visiting China. They were small wins in the scheme of things, but the prime minister hailed a clutch of business deals as the start of a new economic partnership. The “ice age” of the past few years “is thawing,” he told The Observer. “It’s the pragmatic, consistent engagement that provides the certainty to business.”

The prime minister insisted the recalibration of Britain’s place in the world was not a reaction to the chaos and crisis of the past few weeks. “It’s a thought-through strategy,” he said, describing the US, the EU and China as three unequal sides of a diplomatic triangle. “We’re living in a very volatile world. We have to keep our eyes on what’s in our national interest. People are often saying to me: ‘Are you going to choose the US or are you going to choose Europe or are you opening up to China?’ And the answer is we’re not choosing between these things.”

Keir Starmer visits Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai on Friday

But he admitted that the White House had created some “pretty fulsome” challenges in recent weeks recently. “We had a tariff threat, we had Greenland, we had stuff said about Chagos and then we had the Afghan Nato comments,” he said. “Then President Trump phoned me on Saturday afternoon to talk through a number of things in a perfectly constructive way, and therefore it proves again to me that you can have strong relations with other countries notwithstanding the differences.” It is a message he would apply to China as well as the United States.

With an unpredictable US president making America an increasingly unreliable partner, the UK can no longer afford to ignore the world’s second largest economy. The old rules-based global order is collapsing and the balance of power is shifting from west to east. Already China is Britain’s third biggest trading partner, supporting 370,000 jobs. Its increasingly wealthy population of more than 1.4 billion people makes it a valuable market.

Related articles:

But there is more to the thaw than commerce. China has also become a technological superpower, at the cutting edge of innovation in life sciences, robotics, artificial intelligence and quantum computing. It is investing 20 times more in research and development than the UK, and producing 3.5 million science, technology, engineering and maths graduates a year. Jonathan Symonds, chair of GSK, who was part of the business delegation travelling with Starmer, said there was an “explosive” creativity to China’s scientific research.

The prime minister and his advisers have been impressed by this dynamism and impatience for change. The book currently being discussed in No 10 is Breakneck by Dan Wang, which details China’s “breathless and at times reckless speed” in delivering government programmes and infrastructure projects. While Britain has spent decades failing to build a high-speed train line from London to Birmingham, China has created the world’s longest fast-rail network and is now is trialling trains that run at 1,000km an hour. The average cost of building a high-speed line in China is $33m a mile, according to Wang. Some estimates suggest that HS2 will cost £1bn a mile.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

‘This proves you can have strong relations with other countries notwithstanding all the differences’

‘This proves you can have strong relations with other countries notwithstanding all the differences’

Keir Starmer

There is a similar story in aviation and energy. The UK argues endlessly about whether to add a third runway at Heathrow, but China is whacking up eight new airports a year and has 31 nuclear power stations under construction. The Chinese have more wind and solar power capacity than any other country. Robots churn out wind turbines in giant dark factories – the lights are turned off, keeping production costs down, because humans do not work on the production line.

Wang draws a contrast between China as an “engineering state” which can’t stop itself from building and the USas a “lawyerly society” which blocks everything it can. He thinks it is no coincidence that the Chinese ruling elite is made up almost entirely of engineers (Xi studied chemical engineering at university) whereas in Washington and Westminster politics is dominated by lawyers like Starmer.

Of course the flip side of Chinese efficiency is an erosion of individual rights. Xi does not have to worry about judicial reviews or winning elections. As Wang points out, the Chinese Communist party is as interested in social engineering as physical engineering. But the prime minister left China praising Beijing’s “can do” attitude and that there were the lessons to be learned about the “pace and scale” of government infrastructure projects and the need to “unblock” delays.

Starmer insists the government is not turning a blind eye to China’s human rights abuses and the national security threat it poses. The second item on the agenda for his meeting with Xi was headlined “global affairs”. This was the point at which he set out the government’s concerns about the treatment of Jimmy Lai (the UK businessman who has been convicted of “colluding with foreign forces” in Hong Kong), the rounding up of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang by the Chinese state, and the sanctioning of British MPs and peers.

The hailing of “mutual trust” by the Chinese president was rather undermined by the fact that the entire UK government delegation arrived in China with burner phones and disconnected laptops so the Whitehall system could not be hacked. Ministers even had to leave their Apple Watches and AirPods at home.

There will be limits on the collaboration with China. Kyle stressed that there would be “guardrails” in place that created a “safe zone” where deals could be struck. “There has been no point during this visit that we have felt we are taking a risk with national security because we are desperate for growth,” he said. But it is unclear exactly where the boundaries will lie. Last year Ed Miliband, the energy secretary, announced that China would be banned from investing in the Sizewell C nuclear power station, but the government has not yet made up its mind whether windfarms will be defined as “critical infrastructure”. Starmer has delayed a decision about whether to allow a Chinese energy company, Ming Yang, to build the UK’s largest wind turbine manufacturing facility in Scotland.

The government cannot brush aside the risks of doing business with China, but the CEOs and cultural figures travelling with the prime minister stressed that it would also be a mistake to ignore the opportunities. Will Butler-Adams, CEO of Brompton Bicycle, has just closed his stores in New York and Washington, opened a shop in Shenzhen and doubled the size of the one in Shanghai. China now represents more than a quarter of his company’s sales. America, with an erratic president threatening tariffs, “is too risky,” he said. “China offers stability, and that’s what business needs.” Greg Jackson, head of Octopus Energy, warned that the UK will be left behind if it turns its back on China. “It’s not about cheap labour or subsidies; it’s about the tech. I’m not misty eyed, but you are naive if you are not open to it, because with technology progress is exponential.”

In his meeting with Starmer, Xi told the story of blind men being presented with an elephant. One feels the leg and thinks it is a pillow, another touches the belly and thinks it is a wall. It is a Chinese metaphor for failing to see the full picture. The broader and deeper engagement the UK and China have embarked on is “our way of seeing the whole elephant”, the prime minister said. He will have to keep his eyes open to make sure he does not get trampled under foot.

Photographs by Simon Dawson / No 10 Downing Street, Carl Court/Pool Photo via AP