Nicaraguan exiles fear the long hand of Ortega after dissidents of the dictator’s brutal regime were killed in Costa Rica

Claudia Vargas lingers on the memory of waking up on 19 June. Her husband, Roberto Samcam, had teased her for being slow to get out of bed, before going to make breakfast: a Mexican recipe he was practising. By the time it was ready she was running late, and flew out the door promising to eat it in the office.

Before she arrived, her phone rang with barely comprehensible news: Samcam had been shot seven times near the door to their apartment. “In that moment, I felt something shatter in me,” said Vargas.

Samcam was a 66-year-old retired Nicaraguan army major who had become one of the most vocal critics of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo, the authoritarian husband and wife team that has run the Central American country for almost two decades.

Mass protests demanding their resignation were crushed in 2018, with more than 300 killed. In the years since, 200,000 asylum seekers, Samcam and Vargas among them, have fled to neighbouring Costa Rica.

Costa Rica had long been seen as the Central American exception: peaceful and democratic even as its neighbours went through wars, coups and dictatorships. But when Samcam was murdered this year, Nicaraguan exiles felt the hand of the regime they thought they had escaped reaching across the border, hunting down its opponents.

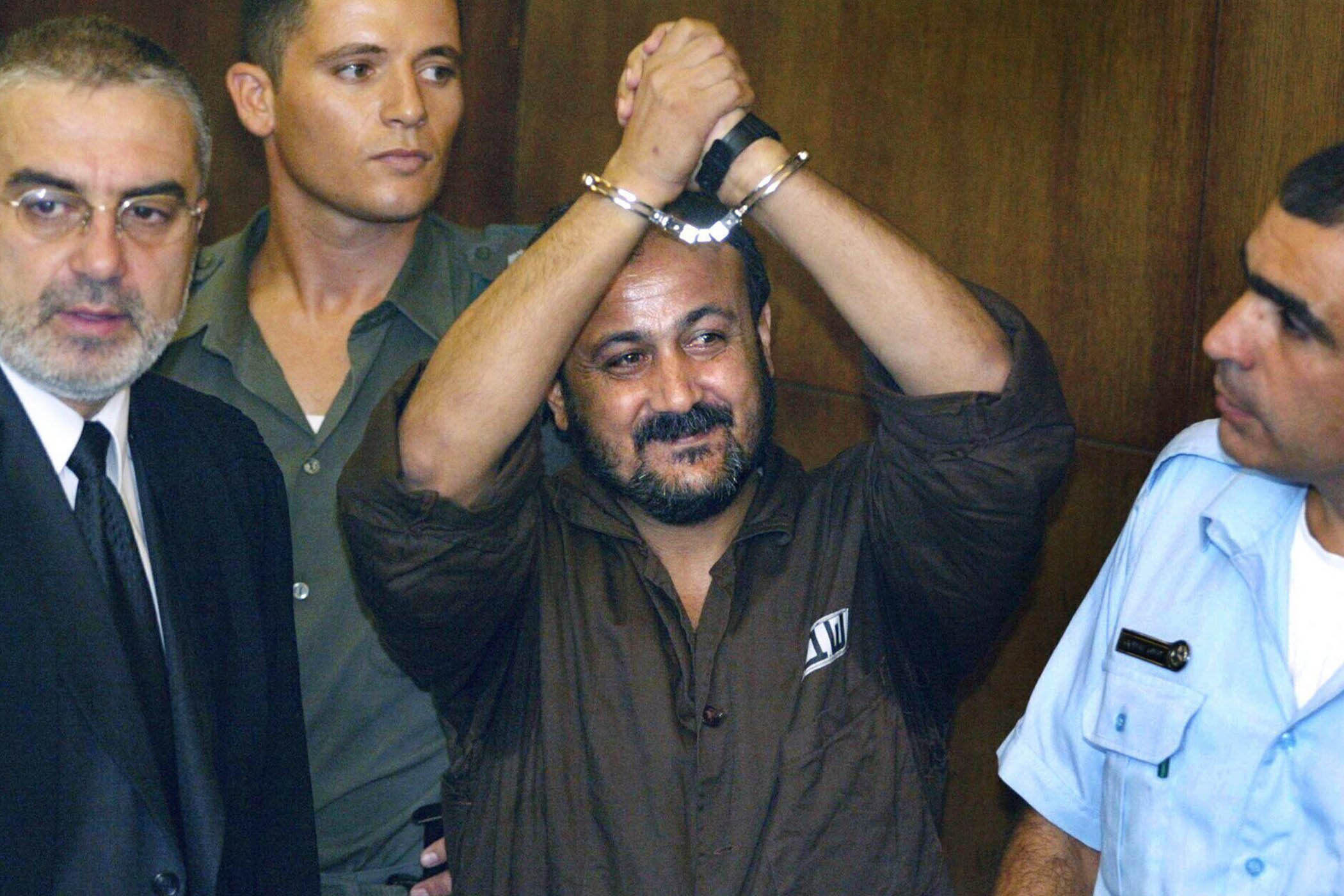

Roberto Samcam

And Samcam was not the first.

On a video call from the US, Joao Maldonado points to the scars where bullets pierced his skin. “All of this is metal,” he said, running a finger along his jaw. For a long time, he struggled to talk.

In Nicaragua, Maldonado, 38, was an engineer and the son of a former army major who went into politics. But when the protests began in April 2018, he, like Samcam, joined in.

“When my father became a Sandinista the principles were revolutionary,” said Maldonado. “But then it stopped being about the wellbeing of the people, and started being about the economic wellbeing of the Ortega-Murillo family.”

As a leftwing revolutionary in the 1970s, Ortega had helped topple a rightwing dictatorship, before leading the Sandinista government in a bloody war against a collection of counter-revolutionary groups, the Contras, who were backed by the US.

They made peace in 1989 – but a year later the Sandinistas were stunned when Ortega lost an election. When he won back power in 2007, he and Murillo, his wife and co-president, made sure they would not lose it again.

Protests were triggered by an attempt to cut welfare benefits that caused years of pent-up anger over corruption and authoritarian creep to explode. Crowds of flag-bearing Nicaraguans took the streets and set up barricades on main roads, where they clashed with pro-Ortega gangs while attempts at national dialogue foundered.

For months, Maldonado helped to man the barricade on the Pan-American highway, a vital trade route that runs the length of the Americas, at the point where it passes his home city of Jinotepe.

Then, on 8 July, thousands of soldiers encircled them, “as if they were going to war with us”, said Maldonado.

He fled the ensuing bloodshed. With an arrest order out for him, it took five days of hiding in safe houses and evading military checkpoints to reach the Costa Rican border.

But even in Costa Rica, things were tense, said Maldonado, adding that they could see the Nicaraguan embassy inflating its personnel with agents to monitor the diaspora.

Come 2021, Maldonado was working as a delivery driver. And at 4.30pm on 11 September he was in a car with a colleague, waiting at a red light, when someone on a motorbike stopped by the window and pulled out a gun.

Maldonado instinctively raised his arm to shield his face. He was hit five times, one bullet reaching his heart. He managed to stamp on the accelerator and get out of danger, then told his colleague, who was miraculously unscathed, to get him to a hospital.

Maldonado had been organising an exiles’ march against the Nicaraguan regime for the next day. “It went ahead: they didn’t want to let fear and terror win. But fewer people went.”

At first, not everyone knew what to make of the attempt on Maldonado’s life. But soon a pattern emerged.

In June 2022, Rodolfo Rojas, a former Sandinista activist who had been living in Costa Rica, was found dead in Honduras, by the border with Nicaragua, with four bullet wounds.

In 2023, Erick Antonio Castillo, a former political prisoner who denounced the torture he had endured, was shot dead in Costa Rica, near the border with Nicaragua.

In 2024, Jaime Luis Ortega, who fought the Sandinistas in the 1980s, was shot dead in the small Costa Rican town where he lived as a refugee.

That year there was another attempt on Maldonado’s life.

By then he was in Costa Rica’s victim protection system – but he still had to work. “This was exploited by the agents of the dictatorship,” he said. “And I fell for their trap.”

A Nicaraguan journalist, Danilo Aguirre, told Maldonado he had a job for him, and sent him a time and place to meet. Maldonado went along with his wife, Nadia Robleto.

Joao Maldonado

This time, it was eight bullets. “They wanted to make sure we didn’t survive,” said Maldonado. “In spite of everything, we did, thanks to God.”

But Maldonado’s internal organs were ruined, and a bullet hit Robleto’s spinal cord. They spent seven months in hospital, recovering, before being resettled in the US. “Nadia is in a wheelchair,” he said. “She lives with terrible pain.”

“And then there is the psychological damage,” he added, simply.

Samcam had been on alert since the first attempt on Maldonado’s life in 2021, said Vargas. He had begun investigating the attacks, speaking to witnesses and families of the victims.

“He’d put all the documents on the table and draw the lines between them,” she said. “He had no doubt these were political assassinations, and that behind them was military intelligence.”

All the victims had opposed the Sandinistas in one way or another. They were among the many who had gathered in Costa Rica – not just for safety, but to stay close to Nicaragua, and organise resistance to the regime.

In Nicaragua itself there is essentially no opposition, independent media or civil society. Nor are there free elections: in 2021, the regime arrested Ortega’s main rival, among others, before claiming Ortega had won 76% of the vote in an election described as a “farce” by international observers. Arbitrary detentions and forced disappearances are common.

People are afraid to speak out, said Dulce Porras, a 74-year-old former Sandinista guerrilla, who went into hiding after receiving threats in Costa Rica. “There’s a terrible silence in Nicaragua.”

All of which made the hub of resistance that was developing in Costa Rica more attractive for Nicaraguan exiles – and more of a threat to the regime.

Vargas has run over every detail of that morning countless times. She didn’t see anything strange when she left home – but then she was never the observant one. That was Samcam: he was hyper-vigilant, even paranoid.

When Vargas got home the police wouldn’t let her in: she would contaminate the crime scene. But they said they thought the assassin had slipped through a window that was being repaired to slip into the building, before approaching the door to their apartment.

“After that, I can only guess at what happened,” said Vargas.

Most people have gone silent. They don’t want to give names or denounce what’s happening

Claudia Vargas, the widow of Roberto Samcam

Four months on, the authorities have so far arrested four Costa Ricans in connection with the murder. They are yet to identify the motive or the mastermind behind it, but the attorney general has said one line of investigation points to it having been ordered by the Nicaraguan army.

In September, the UN released a report confirming what Nicaraguan exiles in Costa Rica had been saying for years: that the Ortega-Murillo regime runs transnational networks that surveil, threaten and perhaps even kill its opponents. All of this has had a chilling effect on the diaspora. Some no longer feel safe in Costa Rica and have moved to Panama, Mexico or Spain.

“It’s almost as if we were in Nicaragua here in Costa Rica,” said Yader Valdivia, from Nicaragua Nunca Más, a human rights organisation. “Most people have gone silent: they don’t want to talk or give their names or denounce what’s happening. The effect has been to disintegrate organised civil society in Costa Rica.”

The murder of refugees demands a response from the Costa Rican government. But President Rodrigo Chaves, who came to power in 2022, is yet to comment on Samcam’s murder. In the past, he has denied that Sandinista cells operate in Costa Rica.

“The silence is unacceptable,” said Vargas. “The border of the country you represent is being violated. Even if you don’t want to respond for us, you have to for Costa Ricans. You have to send a message.”

But if the Ortega-Murillo regime killed Samcam to silence his criticisms, it has had the opposite effect.

“When Roberto died, I inherited his power,” said Vargas, who works for Fundación Arias, a pro-democracy NGO, and recently denounced Nicaragua’s transnational repression at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva.

“The grief is personal and political,” she said. “The political meaning is clearer to me. The personal is much harder to understand. I lost my companion. There isn’t a day when I don’t collapse for a moment. The pain is terrible. It’s an injustice that hurts the soul.”

Vargas says she hears Samcam’s voice in her head, telling her to be careful. “But to be silent would be to give them victory over Roberto’s body,” she said. “And I won’t do it.”

Photographs by Ezequiel Becerra, Inti Con/AFP, Getty