Everyone is talking about Brigitte Bardot. Given the announcement of her death at the age of 91, this should come as no surprise. What is novel is the level of confusion we seem to be experiencing trying to frame a legacy that is anything but tidy. In death as in life, Bardot is a confusing, polarising figure.

Responses across France, the UK and the Middle East, in particular, have been wildly uneven. Some outlets foreground her hateful convictions, many scarcely mention them. Lebanese media has been waxing lyrical over her glamorous visit to Beirut in the 60s, showing pictures of her dressed in traditional Arab clothing, which might provoke an appropriation furore today. Many are playing it safe with a “life in pictures” – and the pictures are admittedly fabulous. On my own social media feeds, the tributes and denunciations arriving from around the world have given me whiplash: friends from different backgrounds variously hailing her as a great woman, a terrible human being, and a “raging racist”. The truth is more nuanced, more interesting, and certainly more perplexing.

I started digging into BB’s biography while writing my forthcoming book A History of France in 21 Women. Working out who would make the cut was challenging, with my publisher drawing a line at two 20th century Simones: Veil and de Beauvoir. With much chagrin, I cut Madame de Beauvoir. But BB never raised a question.

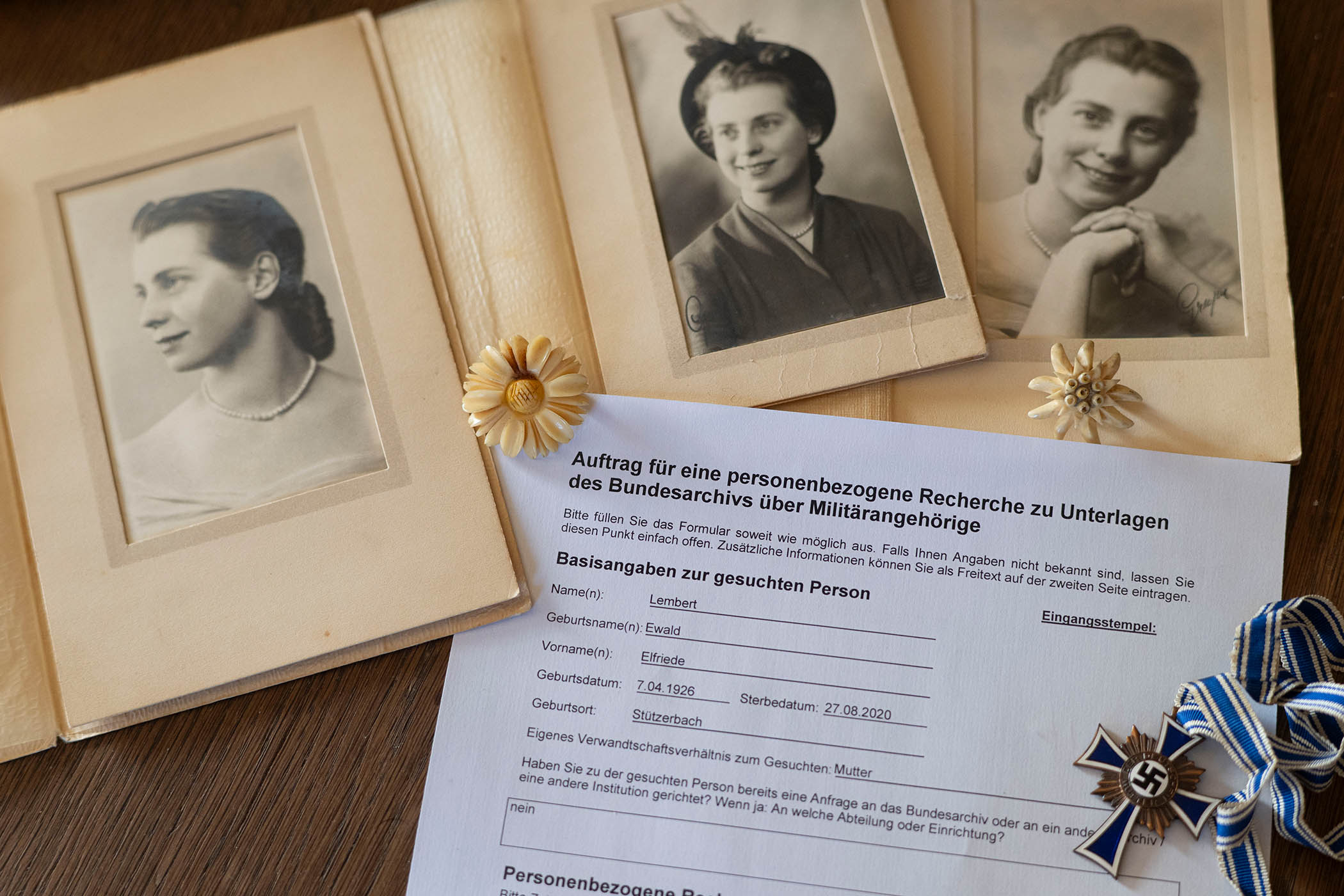

Brigitte Bardot on the set of Les Femmes, 1969

The subject of my final chapter, I chose to feature Bardot alongside Eleanor of Aquitaine, Olympe de Gouges, Coco Chanel and Simone Veil because I wanted to include women who presented different faces of French feminism and embodied major cultural or political change. I didn’t want simple heroines, easy idols.

Bardot transformed cinema by altering how women’s desire appeared on screen

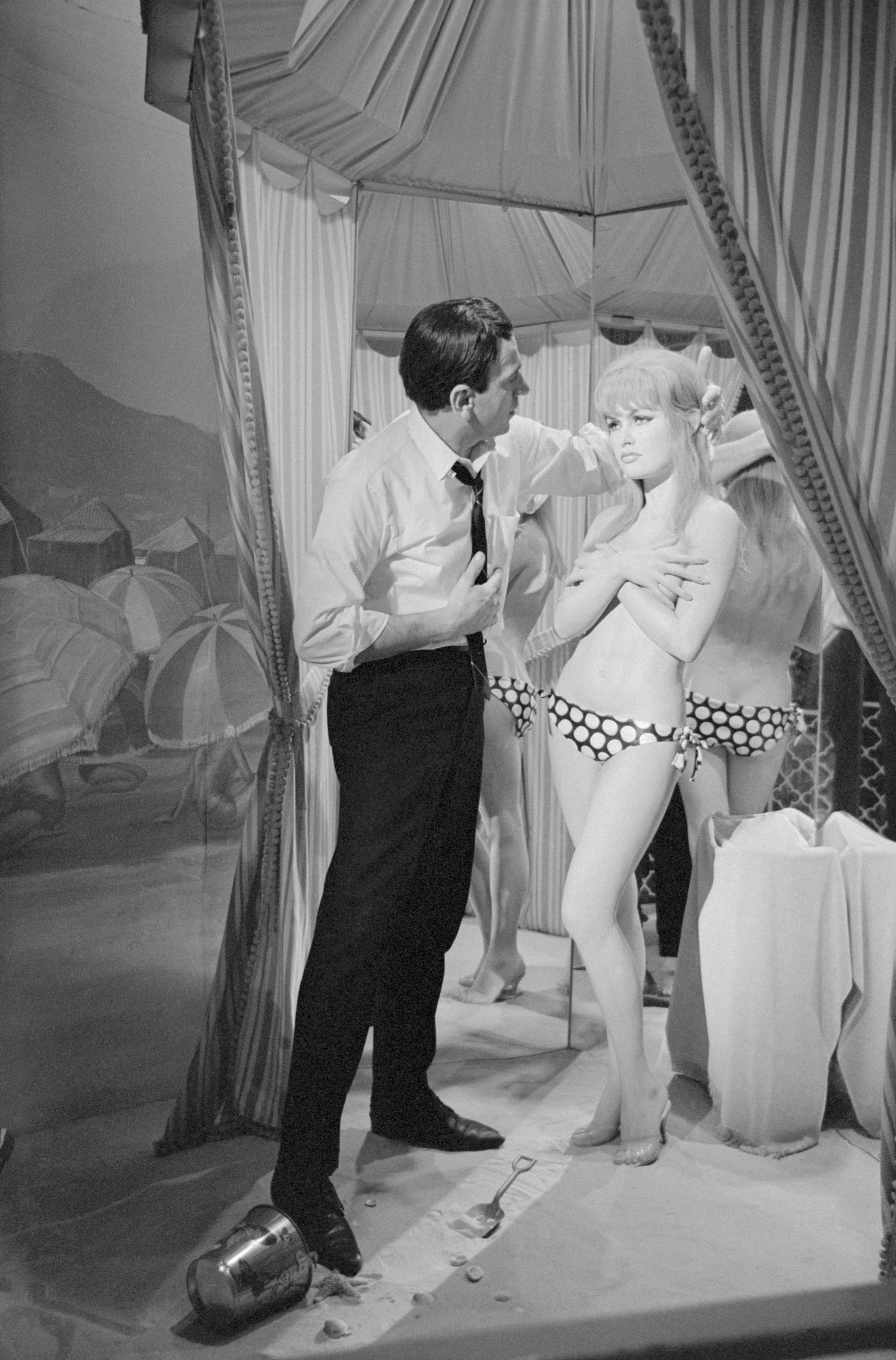

Few figures so perfectly embody the contradictions of modern celebrity as BB: sexual liberation and rightwing politics, vulnerability and hostility, feminist impact without feminist allegiance. Bardot transformed cinema by altering how women’s desire appeared on screen in films such as And God Created Woman. She scandalised audiences not simply through nudity or suggestion, but by behaving as if her body belonged to her, and being unashamed of her sexuality. For a postwar culture still clinging to conservative values that really was revolutionary.

Related articles:

Bardot as Juliette Hardy with director Roger Vadim in his 1956 film Et Dieu... Créa la Femme ( And God Created Woman )

Simone de Beauvoir saw this clearly. Writing in her 1960 essay Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome in 1960 de Beauvoir characterised Bardot as a pioneering force pulling the women’s movement forward – whether the star intended to or not. Yet Bardot recoiled from feminism. She mocked women’s movements, distrusted collectives, and insisted she had simply lived as she pleased. That tension is the point.

Bardot argued that actresses who accused powerful men of harassment were often merely seeking attention

Her dismissiveness of feminism surfaced most visibly in her response to the #MeToo movement. In 2018, Bardot mocked it as “hypocritical and ridiculous”, arguing that actresses who accused powerful men of harassment were often merely seeking attention.

Bardot’s personal life complicates matters further. She was born into privilege, but not into freedom. She lacked a really thorough education and was pushed to commercialise her looks from adolescence. As a teenager she entered relationships with older men – most notably director Roger Vadim – in an industry with little protection for young women. By today’s standards, we might well describe this as grooming or exploitation, even if Bardot never framed it that way.

Bardot plays Dominique who is being tried for murder in La Vériteé ( The Truth ), directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1960

Bardot would write openly about her struggles with mental health in her memoirs. As an adolescent she attempted suicide. She spoke of feeling suffocated by fame, uncomfortable with her own image, hunted by cameras. Motherhood, when it came, was experienced not as fulfilment but as invasion. Many have criticised her as a terrible mother (which, arguably, she was), and indeed her son sued her for breach of privacy, when she famously wrote that she saw her baby as a “tumour’”and would rather have given birth to a puppy than a son.

Bardot with her son, Nicolas, on a skiing holiday in 1960

But Bardot never wanted to be a mother, and during her pregnancy she suffered real psychological trauma, describing attempts at self-abortion by punching herself in the stomach. Abortion was not legal at the time, and she had no option but to continue with a pregnancy she did not want. Eventually, she gave up custody of her son.

Pictured here in the early 70s, Bardot was a vocal animal rights activist

Bardot retreated from cinema when she was 39, fleeing a culture and way of life that was damaging to her. She replaced it with something more wholesome: animals. Her devotion to their welfare was genuine, sustained, and life-defining. It also became the lens through which some of her darkest and most problematic views were expressed.

From the 1990s onwards, Bardot accrued multiple convictions for hate speech in French courts – targeting Muslims, immigrants, and overseas French communities. Her language was crude, racialised, and inflammatory. While her diatribes usually started by condemning animal rights violations and animal sacrifice, it often descended into racism, and she aligned herself openly with the French far right. She was fined tens of thousands of euros for this, and was broadly unrepentant.

Bardot, pictured in 2005

Bardot exposes a modern problem: our inability to hold influence and imperfection in the same frame. She was never a role model, she was a force. A woman with a vast capacity for kindness – especially towards animals – and an equally vast capacity for prejudice. Her life was anything but charmed.

Rather than prosecuting or rehabilitating her, we might accept that Bardot’s legacy resists retrospective correction. Her impact is undeniable; her presence mesmerising, even when her politics might repel us. The unease she leaves behind may be the truest measure of her significance. One thing is certain: she was a disruptive force, and the world still can’t look away.

Katherine Pangonis is an author and historian based in Paris. Her book, A History of France in 21 Women, is published by Oneworld on 5 March

Photographs by Len Trievnor/Daily Express/Hulton Archive, Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images, Han Productions - CEIAD, Gamma-Rapho, Christian Brincourt/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images, Alamy