Francis shook up the Catholic church to acknowledge the gulf between its ways and the ways of the world. Now it falls to his successor to bring about change

Are we at the most crucial pontifical crossroads of all time? As cardinals gather in Rome for the conclave that begins this week, there’s a feeling in some quarters that the next papacy will be pivotal.

To be fair, that has often been the mantra. In 30 years of reporting on the Catholic church, often from Rome, one of the phrases you hear most is that everything hangs not on this pontificate, but the next – that only if the next pope goes in the same direction as the last, will anything change.

And perhaps it’s understandable that in an organisation that selects its leader from the ranks of ageing men – Francis was 76 when he was elected – thoughts quickly turn to what will happen when the incumbent dies. Especially since the system equates to an absolute monarchy: the man who wears the white cassock calls the shots.

This time, though, things are different. Before Francis, popes tended to ignore the elephants in the nave. Homosexuality was “disordered”; remarriage after divorce was prohibited, and in 1994 Pope John Paul II pronounced that not only would there never be women priests, but that the question would never be debated again. The Catholic church seemed to move in a separate realm from the rest of the world, where LGBTQ+ people had the same rights as anyone else, where women were equals in the workplace and in leadership roles, and where divorce was seen as no-blame and people had a right to start again with a new relationship.

But over the past 13 years all that has shifted. Not because Francis will be remembered as a reformer: his attempts at reform were often deemed failures. He set up a commission in response to the child sex abuse scandal, but high profile members resigned as they thought it wasn’t going far enough, or fast enough.

But what he did do was shake up the church to acknowledge the gulf between its ways and the ways of the world. His approach to the issues that had been so divisive differed from that of his predecessors: soon after his election in 2013, in response to a question about gay priests, he famously asked: “Who am I to judge?”

He realised, too, that the church couldn’t go on excluding lay people from decision-making and from sharing their views on how the church should be run. To that end, he put in place a worldwide listening exercise, the clumsily-named Synod on Synodality.

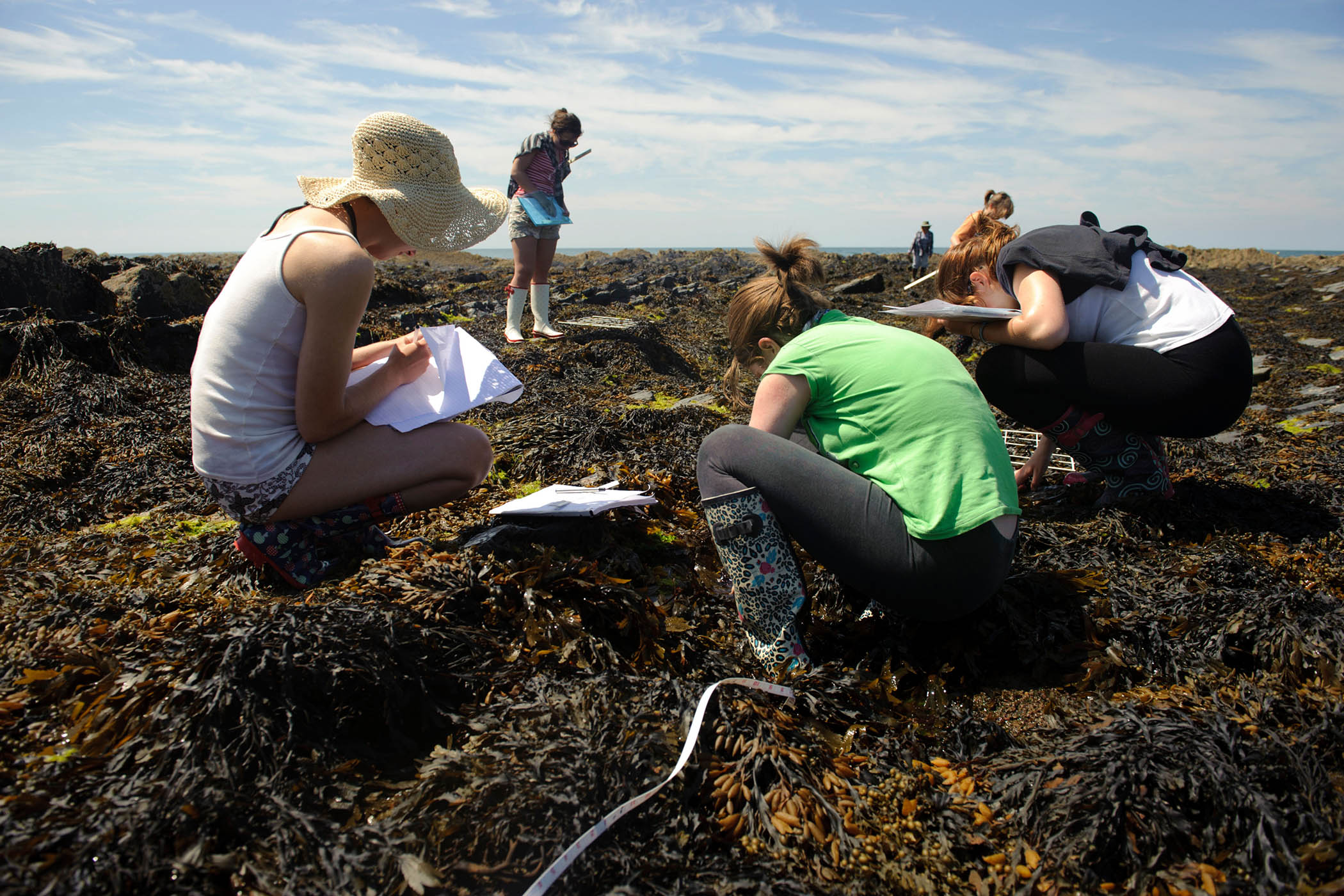

Across the globe, from parishes to dioceses, lay people were invited to share their views on what mattered to the future of the church: never in the history of Catholicism had non-ordained people been taken seriously as co-architects of blueprints for the church’s future.

And the final document that emerged from the process was clear on the issues people thought the church should prioritise: more lay and female involvement in decision-making, better accountability, a more understanding approach to the LGBTQ+ community, and to those who had divorced and remarried.

But then, nothing happened. In letting the genie out of the bottle, while failing to come up with any concrete way forward on the crucial issues, Francis has left the church in a precarious position. It meant he was generally perceived as a liberal, despite few reforms and a frequent undertone of traditionalism. In turn, the powerful US right took against him.

However, in Britain new figures on Mass attendance from the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales show an increase in churchgoing, especially among the young, with Catholic Gen Z-ers outnumbering Anglicans by two to one.

The next pope faces a choice: enact the reforms Francis was too scared to push through or return to a more traditional world that may alienate the new generation. The stakes could hardly be higher.

Photograph John Wessels / AFP via Getty Images

Who might be the next pope?

By Jonathan Lewis

Pietro Parolin

Considered the frontrunner in a crowded field, Cardinal Pietro Parolin has served as the Vatican’s secretary of state since 2013 under Pope Francis. A diplomatic insider from Italy, he’s seen as a steady, moderate figure who would continue Francis’s direction – but with a more cautious and understated tone. Parolin was involved – but not charged – in the Vatican’s botched London property deal that led to a major 2021 trial. He has criticised same-sex marriage, calling Ireland’s 2015 vote a “defeat for humanity”.

Péter Erdő

Cardinal Erdő, archbishop of Budapest and primate of Hungary, is the leading conservative candidate and likely challenger to Parolin. Twice elected head of Europe’s bishops’ conferences, Erdő is highly regarded among European cardinals, the biggest voting bloc of electors. He believes marriage is indissoluble and has opposed the practice of divorced or remarried Catholics receiving Holy Communion. Raised Catholic under communism, he once likened welcoming migrants to human trafficking.

Luis Antonio Gokim Tagle

Cardinal Tagle of the Philippines is the most liberal of the frontrunners and a favourite of Pope Francis, who brought the former archbishop of Manila to Rome to lead the Vatican’s missionary evangelisation office, serving much of Asia and Africa. In 2015, Tagle urged the church to reassess its “severe” stance toward gay people, divorcees, and single mothers, saying past harshness had caused lasting harm. The Philippines has the third-largest Catholic population globally, and with Catholicism’s centre shifting towards Asia and Africa, Tagle may be a strategic choice.