Gianni Infantino sent his apologies. In a video address played to the dozens of dignitaries and executives enjoying the hospitality lounges at Eden Park, the Fifa president expressed his sincere regret that he could not be with them, watching performances from tattooed Maori warriors and Pacifika dancers in spectacular head-dresses.

He had, at least, a valid excuse: ever the globe-trotter, Infantino was in Morocco, watching Afghanistan’s women’s team taking part in an exhibition tournament, assiduously documenting it all for his lively Instagram account. Still, he wanted those gathered 12,000 miles away in Auckland to celebrate the birth of the world’s newest professional league to know they had his backing.

Oceania – the region that encompasses New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and a host of Pacific island nations – was the last of Fifa’s confederations not to have a professional club competition. The event at Eden Park, late last October, was a “soft launch” for the OFC Pro League, the tournament that has ended that wait.

Representatives of all eight of the league’s clubs, drawn from across the South Pacific, had been flown into Auckland; they were joined by Lambert Maltock and Franck Castillo, the president and general secretary of the OFC, the game’s governing body in the region, and the driving forces behind the project. Though Infantino could not be there, his video message made it clear the league had his seal of approval. That has been his consistent position. He has been an advocate of the idea for more than two years, ever since the project was presented to him by Maltock at a meeting in Paris in 2023.

He pledged Fifa’s “full support to help our friends and colleagues in Oceania to make this proposal become a reality” immediately after those talks. A few months later, while in Auckland for the start of the Women’s World Cup, he echoed the sentiment. His video message in October told the delegates at Eden Park that the Pro League would “elevate football in Oceania to the global stage”, as a press release later summarised it.

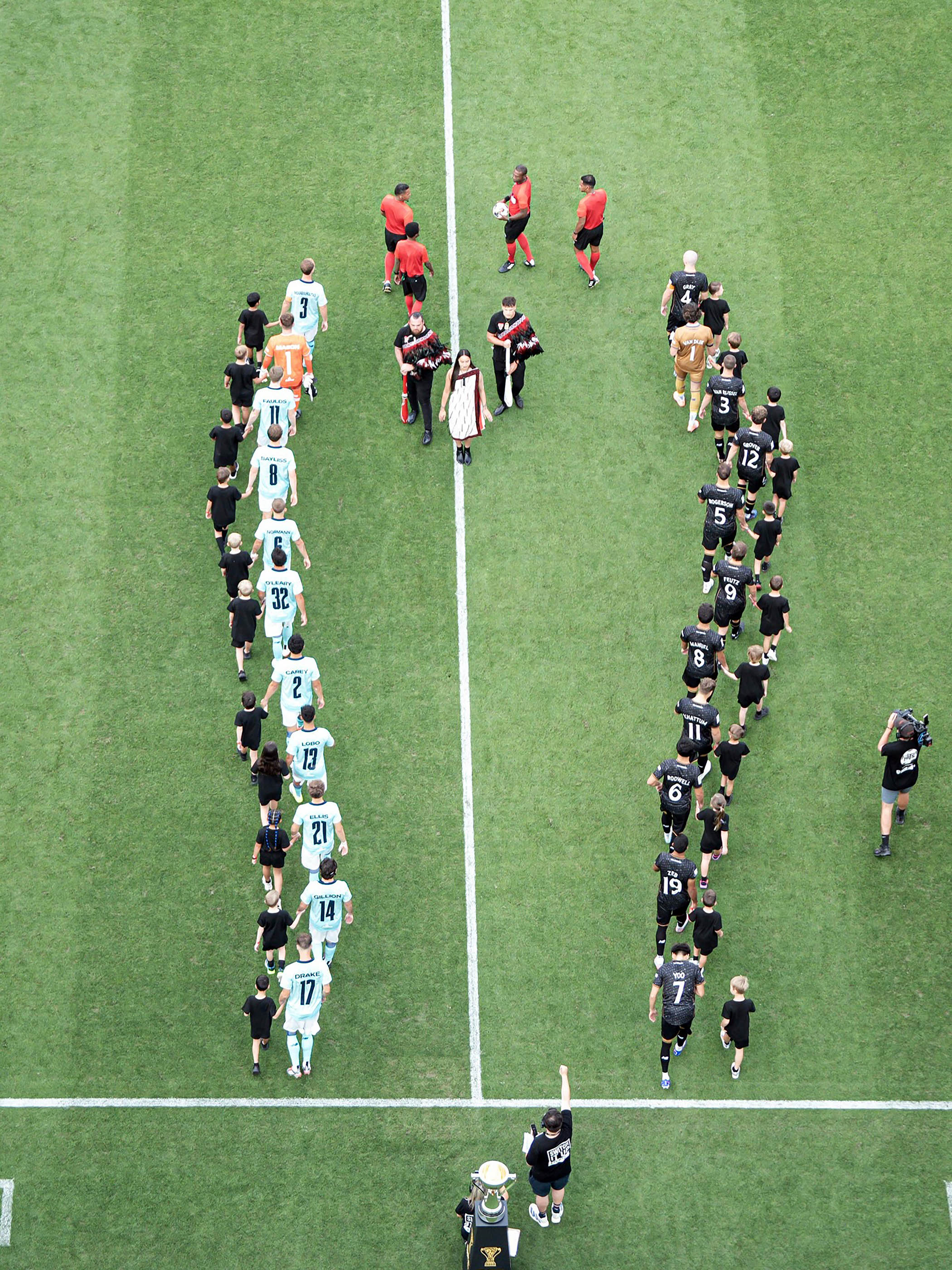

That is what Maltock hoped, too. The league played its first games at Eden Park yesterday; it was advertised as not only family-friendly fun, but as a chance to celebrate Pacifika culture, too. Fans were encouraged to bring drums and guitars for the opening fixture, a 2-2 draw between Vanuatu United and Bula FC. It was the culmination of Maltock’s vision of a league that would accelerate the game’s growth in the region, helping the area’s national teams, club sides and players to compete on the international stage. The Pro League, he has always maintained, will “change the football landscape for ever”. His focus, of course, is on what it might do for the game in Oceania. In time, though, the tournament’s impact may well be felt far beyond the Pacific: in the game’s corridors of power; at the next instalment of the expanded Club World Cup, Infantino’s brainchild; and even, possibly, in the very structure of domestic leagues, from the Baltic to the Irish Sea and on to the Gulf of Mexico.

The OFC Pro League, after all, is not just a cross-border competition; it is also a cross-confederation one. As well as teams from New Zealand, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Tahiti, it includes South Melbourne, a longstanding team who compete in the second tier of Australian football, a competition governed by Asia.

There are, across football, a number of groups lobbying for competitions that would change the football landscape

There are, across football, a number of groups lobbying for competitions that would change the football landscape

They have been included partly through history – they were voted Oceania’s club of the century before Australia switched confederations in 2004 – and partly necessity: Australia represents a television market that the new competition could not afford to ignore. Maltock’s vision does not stop there; he hopes that they might, one day, be joined by a side from Hawaii, which falls under the remit of Concacaf, the game’s governing body in North America.

Related articles:

That has not gone unnoticed. There are, across football, a number of groups lobbying for competitions that would – in Maltock’s words – change the football landscape. There are teams in Belgium hoping to join forces with the Netherlands’ Eredivisie. Some Mexican sides have discussed trying to combine with Major League Soccer in the United States.

A team in Luxembourg, Swift Hesperange, are attempting to challenge Uefa’s right to adjudicate which competitions are permissible through Europe’s court system. And, of course, A22 – the group behind the controversial proposal for the European Super League – continues to pursue its plans to alter or replace the Champions League.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“We’re happy to see something is happening,” said Maksims Krivunecs, the chief executive of the Virsliga, the top flight in Latvia. Reluctantly, to an extent, he has come to the conclusion that his competition should merge its latter stages with competitions in Lithuania and Estonia. “For small regional leagues, it is a natural part of evolution. I think if your domestic league is big enough, you do not need to. But for small leagues, [combining forces] is a necessity.”

His proposal, like a number of others over the last two decades, has faced two primary obstacles. Clubs are reluctant to vote against their own interests; minor teams in the Netherlands, for example, will not approve the creation of a league that costs them lucrative games against Ajax, Feyenoord and PSV Eindhoven. And leagues and national associations will not, as a rule, agree to anything that risks their entry slots to European competitions.

Krivunecs is confident those issues can be overcome. He believes the Baltic will, sooner or later, be the “first” to stage a pilot competition. Uefa’s official stance is that it will fairly consider any viable proposal; that it is yet to approve any is because none has met that bar. That a cross-border league is now operating with the active support of Fifa on the other side of the world is, as Krivunecs put it, an “interesting” development.

The OFC Pro League has not, admittedly, required such diplomatic delicacy. Maltock’s plan had wide support within the region, viewed as the only viable solution to the widening gap between Oceania and the other confederations; that it has been so vocally backed by Infantino gave it an air of both legitimacy and inevitability.

That support is no great mystery. His presidency has been characterised not only by an evangelical desire to promote the interests of the game’s less powerful federations, but also by what feels like a distinctly top-down approach: Infantino’s Fifa has made a consistent effort to construct or expand competitions.

Maltock’s plan, then, would have appealed before he even considered the ancillary benefits: a chance to secure the loyalty of a region that has 11 votes in a Fifa presidential election; and the opportunity to guarantee that Oceania sends a professional team to the next edition of the revamped Club World Cup.

Though the romance of Auckland City’s presence in the United States last summer appealed to many neutrals, some representatives of the club felt, even at the time, like they were something of an afterthought; they assumed, even at the time, it would be their first and only appearance.

The challenges for the Pro League, instead, have been logistical: vast travel distances, variable weather conditions, historic club sides who did not have the resources for full professionalisation.

Fifa has done what it can to help with the latter, in particular, inviting representatives of all eight teams to a retreat in Fiji in September that featured talks from officials who had been involved in setting up Inter Miami and Major League Soccer, among others. It was, those present say, a helpful experience, albeit one which made the scale of the challenge abundantly clear. The OFC, meanwhile, has sourced the money required to get the league off the ground, enabling the teams to pay for travel and accommodation for up to 25 players and staff in each round of games.

In October, Rajesh Patel, the president of the Fijian Football Association, claimed that the league would be bankrolled by a four-year, $20m agreement with the Saudi Tourism Authority. “We are thankful for this investment, which makes professional football a reality in our region,” he said, at the launch of Bula FC, the Fijian franchise in the new league.

Curiously, the OFC has not formally announced that funding; there are, as of the time of writing, no plans in place to make public the deal – which mirrors similar arrangements that various Saudi bodies have with Concacaf, the game’s governing body in North America. The OFC has not disputed Patel’s claim.

Even with that investment, the clubs will still have to bear some costs; as ticket sales for the opening weekend in Auckland are likely to prove, it will take time before the venture becomes self-sustaining. In Oceania, they believe it will be worth it. It will alter the game’s horizon in its furthest corner; its effects, though, could well be felt closer to home.

Photograph by Shane Wenzlick / www.phototek.nz