This article first appeared as part of the Daily Sensemaker newsletter – one story a day to make sense of the world. To receive it in your inbox, featuring content exclusive to the newsletter, sign up for free here.

The world’s richest 60,000 people control three times more wealth than the bottom half of humanity combined, according to a landmark report on global inequality.

So what? This isn’t the full story. There is a feeling that inequality is on the rise. But although the super rich are getting richer, the overall picture is varied. Inequality

•

remains high; but

•

has fallen significantly over the past century; and

•

is rising in some countries while not changing or dropping in others.

Apples and oranges. Measuring inequality is difficult. Rich people often stash their assets in tax havens, while many of the world’s poorest work in informal economies that lack tax returns. Different ways of parsing the data can also produce vastly different results.

Measured approach. The World Inequality Database, upon which the new report is based, is the most comprehensive effort to track global trends in the distribution of wealth and incomes. Established in 2011, it combines tax data and other information from more than 200 countries.

Related articles:

World in motion. Inequality between countries has fallen sharply, a trend driven by the end of colonialism and the rise of China and India, where hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. East Asia’s share of global income has risen from 8% in 1950 to 25% today, while Europe’s has declined from 40% to 17% in the past 125 years.

Good news. Globally the proportion of wealth commanded by the top 1% ticked up in the 1980s and 1990s, before dropping slightly during the 2010s. Despite these fluctuations, the broad trend is downwards. In 1910 this select group commanded 56% of worldwide wealth. Their share is now 36%, thanks to progressive taxation and the expansion of the welfare state.

Bad news. Things are more complicated on a national level. Poverty dropped substantially in most countries during the first part of the 20th century. But it began climbing again from the 1980s onwards, when deregulation and globalisation took hold.

Case in point. Thirty years ago the richest 10% of Chinese people owned 41% of national wealth, while the bottom half had 16%. Today the elite have increased their share to 68%. The poorest have 6%. The situation is similar in India and the US.

Levelling out. In many countries, this gap is no longer widening. In the 1990s the share of wealth owned by the poorest 50% in the UK fell by more than half, but over the past decade inequality has stabilised. This is also true of China, Germany and Japan. In some places, such as the Netherlands, inequality has slightly decreased over the past 10 years.

Narrowing margins. Meanwhile the gap between bottom and middle British earners is shrinking. Two factors driving this trend are sustained increases in the minimum wage and fewer pensioners in poverty. But a third is diminishing numbers of skilled, middle-income jobs.

Cold comfort. Despite these nuances, there is a widespread feeling that inequality is rising, a perception that helped fuel the outbreak of gen Z protests from Peru to Nepal.

Money talks. This could be because years of inflation and soaring property prices have eroded the purchasing power of middle earners. A lack of stable, long-term jobs is another relevant factor, as is the visibility of elite wealth on social media.

Mind the gap. Inequality also remains markedly high, even where it is stable. Between 2000 and 2024, the richest 1% took 41 cents from each dollar created, compared to the single cent taken by the poorest half of humanity. Nearly everywhere, the top 1% hold more wealth than the bottom 90%.

What’s more... A G20 panel, led by the economist Joseph Stiglitz, declared an “inequality emergency” in November. It said that if the $480tn of wealth created in the past 25 years had been shared more equitably, this could have educated every child, transitioned the world away from fossil fuels, and ended global hunger.

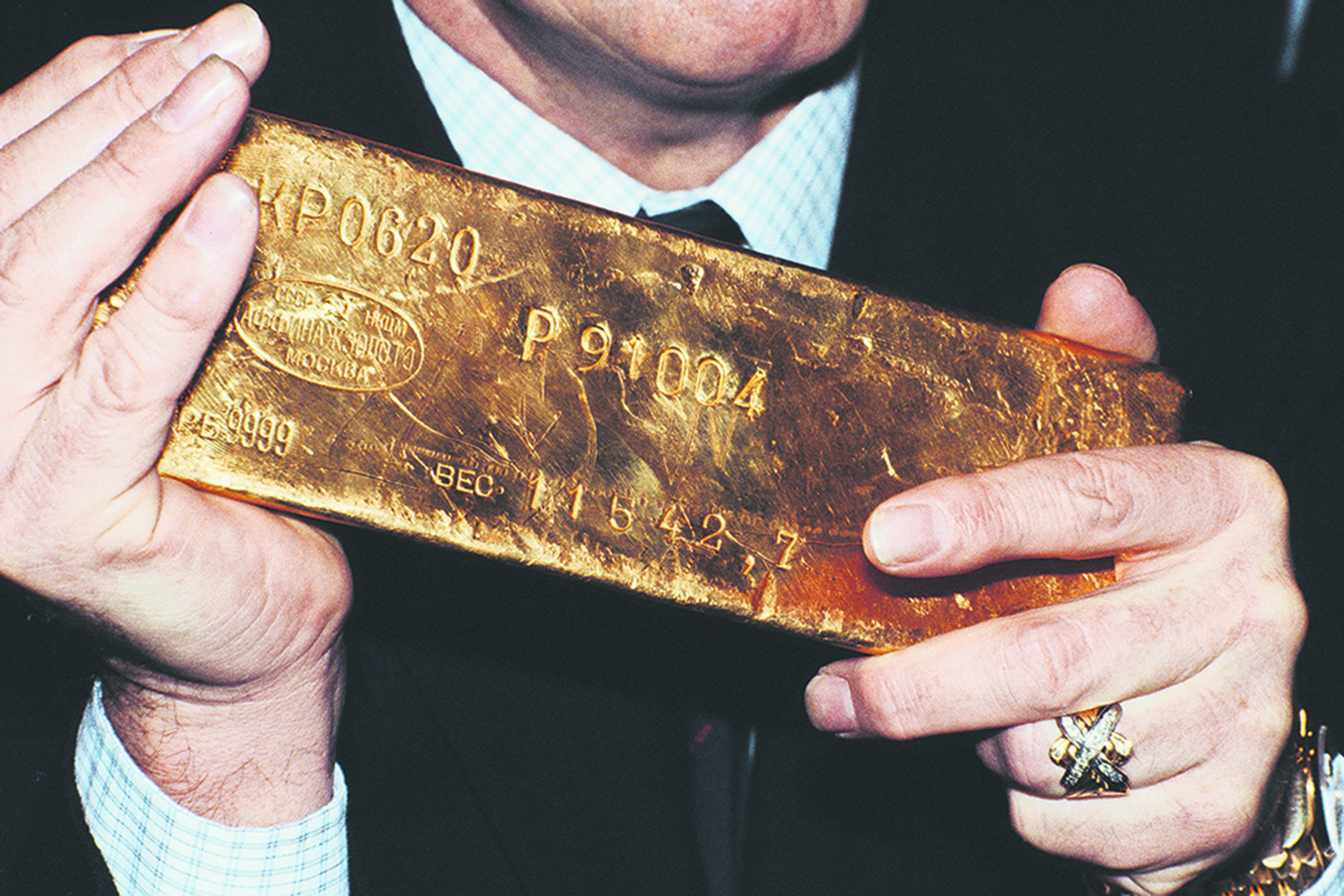

Photograph by Gabriel Bouys/AFP/Getty Images