The Harvard professor on America’s new dogmas and why intellectual freedom is under attack from all sides

Portrait by Simon Simard for The Observer

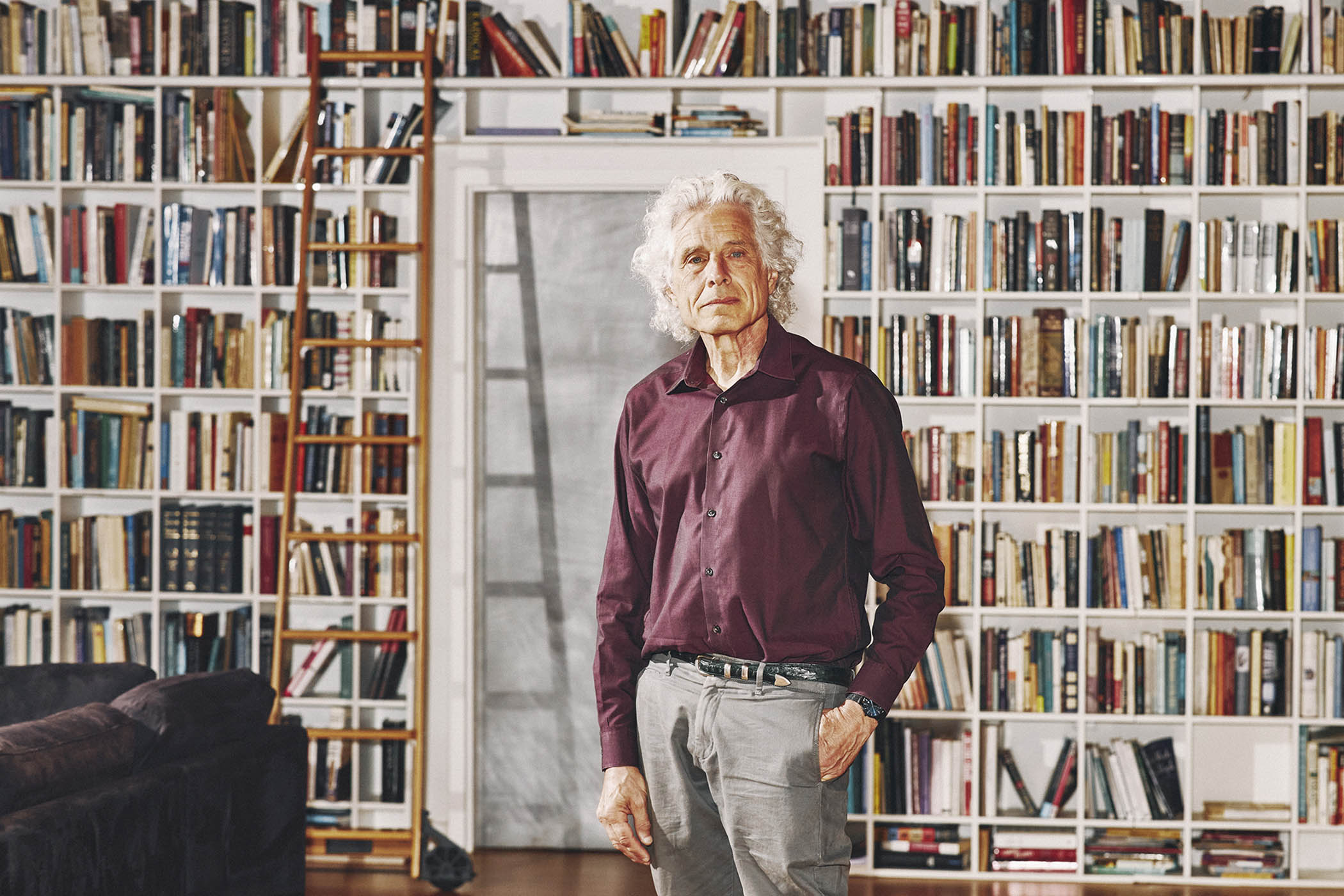

In recent years, Steven Pinker, the celebrated Harvard professor of psychology, has become almost as well known for the controversies he triggers as for the bestselling books he writes. Widely recognised for the breadth of his learning and by the profusion of his silvery locks, he is a leading critic of how American universities, including his own, have grown more proscriptive about what can be written and said.

In April 2023, he co-founded the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard in an effort to combat the bullying and persecution of scholars who stray from an enforced consensus opinion. But now he says he’s doing battle on two fronts. Up until eight months ago, he tells me on a video call from his home in Boston, he thought the biggest intellectual threat to Harvard came from “cancel culture from within academia”. That was before Donald Trump’s administration began withholding scientific research funding to the university.

“That is worse,” he explains, “because the federal government is obviously more powerful than the sociology department or a bunch of aggrieved students.”

A self-described centrist liberal, he is aware that his preference for promoting the rule of law, free press, free speech and science is out of step with an increasingly strident and polarised America. “I fear that because it doesn’t align with the Maga camp or the woke camp, that it’s a disappearing middle,” he says.

Last year, he resigned as honorary president of the Freedom from Religion Foundation (the US version of the National Secular Society), claiming that it had “turned its back on reason” and imposed “a new religion, complete with dogma, blasphemy, and heretics”.

The heretics, in this reckoning, were the people excluded from debates or institutions because they had expressed the belief that biology determines sex. According to Pinker, former bastions of free speech like the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Humanist Association have, under pressure from trans rights activists, adopted “an absolute dogma that may not be challenged”. At one point in our conversation, he says: “I don’t understand how trans activism has devoured every civil liberties and free speech nonprofit in the United States, but I suspect this has happened to some extent in the UK as well.”

It’s the kind of observation that, regardless of its relationship to empirical truth, draws lines, provokes reactions and locates a position in the so-called culture wars. He is well aware that such views help create an image that can overshadow his professional reputation. “I don’t want it to take over my life as a psychologist, as a science writer, as a public intellectual,” he admits.

Perhaps it’s understandable, then, that his latest book, entitled When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows…, looks at first like a careful retreat from contentious issues. Its focus is on what philosophers and game theorists refer to as common knowledge, a term that has a precise scientific meaning distinct from the popular understanding. The subtitle of the book is Common Knowledge and the Science of Harmony, Hypocrisy and Outrage.

I wasn’t aware that there was such a science, but with Pinker there are few areas of life that can’t be subjected to scientific analysis. It’s his hyper-rational, problem-solving approach to the world that led the cultural critic Leon Wieseltier to accuse him of trying to impose “scientism”, the excessive believe in the power of scientific knowledge, on the humanities. Pinker responded by writing Enlightenment Now, an extended argument for the progressive benefits of science and reason. In any case, he assures me that my ignorance is widespread.

“Common knowledge is not common knowledge,” he says. “It’s not part of the vocabulary of most literate people.”

Pinker, though, has done a great deal of research in the field, as well as reading just about everything ever written on the subject. And he’s convinced that it is an unjustly neglected area of intellectual discourse.

“I think a number of the specialists who study common knowledge and its implications would agree with me that it’s a big, important concept,” he says. “It ties a lot of things together, solves a lot of mysteries, but it requires some subtlety to explain what it is and why it matters.”

So what is it? The place to start is with what it is not. It’s not just knowledge that is widely known. Say, for example, you lived in the former Soviet Union. You would have known that there were food shortages, wholesale state censorship and prisons full of people who made the mistake of opposing the government. Everyone else would have known it too, but it would not have been common knowledge.

That’s because you would not have known that everyone else knew, as there was no public forum in which to share such information and ideas. And if you had tried to spread what everyone privately knew, you would have been sent to prison or – in Stalin’s day – shot.

Knowledge that everyone individually knows is not common knowledge but universal private knowledge. Pinker uses the example of Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Emperor’s New Clothes to explain the difference. When the young boy blurts out that the emperor is naked, he is simply saying what everyone already knows, but not, until he speaks, what everyone knows everyone else knows.

Once we know something that everyone else knows, and know that they know it, and they know that everyone else knows, and we know that they know we know, and so on ad infinitum, we have the means of coordinating large-scale solutions to complex problems. In the case of the naked emperor, his subjects can finally acknowledge that he is a spoilt, deluded ruler cut off from reality, and perhaps decide to get rid of him.

The fact of everyone knowing something and knowing that everyone else knows it is the basis, says Pinker, on which so many facets of society rest. Take money, for instance: we pay cash or tap cards for goods on the understanding, universally agreed and acknowledged, that the cash or card reliably represents a certain store of value that we can trust will be honoured.

The same principle applies to the banking system, timekeeping, traffic management and almost any other complex system involving human interaction. The historian and thinker Yuval Noah Harari has argued that organised societies are all founded on fictions, “self-reinforcing myths” that unite human collectives. Pinker admires this insight but provides a different formula: “Our world is built on conventions that allow us to coordinate effectively and are self-reinforcing because they are common knowledge.”

That is the key argument of the book boiled down to one sentence, and much of the rest of it is an interesting but not exactly page-turning discussion of “situations in which rational actors must choose among alternatives whose outcomes depend on the choices of other rational actors”. Cue various game theory scenarios, with titles like Stage Hunt or Hawk-Dove, in which the participants try to work out what to do in the absence of common knowledge.

Social norms exist because everyone knows they exist, and there’s a sense they can unravel

Compared to some of Pinker’s previous bestsellers, such as The Blank Slate or The Better Angels of Our Nature, this new work could easily appear arcane or abstract. Those books had big meaty themes like the essence of human nature and the long-term decline in human violence. They became part of the intellectual and cultural conversation, the kinds of books that were essential to read – even if you disagreed with them – because they were rich in research, highly accessible and bracingly unafraid to challenge received wisdoms.

But just when you may begin to wonder if all the intriguing anecdotes, theories and games in When Everyone Knows will ever lead to something more concrete, there is a sudden change of tone at chapter eight, which is entitled The Cancelling Instinct. It opens with this question: “Do women, on average, have a different profile of aptitudes to men?”

While you’re working out what your answer might be, Pinker follows up with a further 23 questions of a similar challenging kind. Examples include: does racial diversity benefit neighbourhoods, academic departments and companies? Are there two sexes in animals, including humans? Do men have an innate motive to rape? Do the Muslim doctrines of jihad and martyrdom encourage suicide terrorism? Are differences in intelligence between individuals partly heritable? What all the questions have in common, Pinker writes, is that they were raised in recent years by serious scholars who were then “censored, punished, fired, threatened, harassed, demonised, labelled, and in some cases physically assaulted”.After all the dry theorising and thought experiments that make up three quarters of the book, there is a galvanising infusion of jeopardy, morality and reality. It’s as if the psychology professor had taken a rest and been replaced by the campaigner for free expression. Oh, you think, this is why he wrote it.

“No,” he quickly corrects me, when I put this to him. “I would say not, even though it does take up a certain chunk of my professional energy. I’ve been enmeshed in the debates within Harvard on what is academic freedom and how to safeguard it, and in the battles Harvard is facing with the federal government, which is punishing Harvard in part for a lack of diversity of viewpoints.”

Rather, he says, it’s the psychological phenomenon of shaming and demonising people that stirs his intellectual curiosity. “Where does it come from?” he asks rhetorically. “The answer is that our norms are matters of common knowledge. Social norms exist because everyone knows they exist and there’s a sense that they can unravel if someone flouts them without being publicly sanctioned, and that leads to a collective urge to prop up norms by publicly punishing violations.”

Is there knowledge, however, that should not be common knowledge, areas of study that may cause more social harm than scientific benefit? Pinker explores this idea towards the end of the book, using as an example research into the question of whether average racial differences in measured intelligence have genetic, as well environmental, causes. “This issue has set the intellectual world ablaze every time it has been raised for more than half a century,” he writes.

He identifies the potential social harms but doesn’t come down on one side or other of the argument, concluding only that, even if such specific questions should be kept out of common knowledge, the default scientific position must be intellectual freedom.

Using that freedom, the writer Malcolm Gladwell, with whom Pinker has had a series of spats over the years, has criticised Pinker for sourcing material from Steve Sailer, a rightwing blogger known as an “evolutionary conservative” for his beliefs on race. Pinker maintains that the criticism is the fallacy of guilt by association.

“I feel the responsibility to try to share ideas of the liberal enlightenment in order that intellectual life not fracture into mutually uncommunicating tribes,” he says. “There’s the idea that even to talk to them is legitimating all their ideas, but you can’t have an intellectual ecosystem that works like that. You end up with pools of separate common knowledge.”

When Pinker speaks, he has the gift of reducing the thorniest of problems to issues that simply await the application of the most rational solution. It’s both his most appealing strength and his most glaring vulnerability. “There is reason to believe that some of the more extreme beliefs among university students aren’t actually believed,” he says, “but everyone keeps [that] private out of fear of punishment. So if we can generate common knowledge, make what is private public, if the little boy can say the emperor is naked, then the misconceptions can unravel.”

It would be reassuring to think that all struggles for common knowledge could be settled by the shared principle of common sense. But you don’t need to be a psychologist to know that there’s more to dismantling intellectual shibboleths than simple logic. As one of Pinker’s Enlightenment heroes, Immanuel Kant, famously put it: “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.”

Steven Pinker will be appearing live in The Observer newsroom on Monday 29 September, 6.30-7.30pm. Book your ticket here

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows…: Common Knowledge and the Science of Harmony, Hypocrisy and Outrage is published by Allen Lane (£25) on 23 September. Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism