When a group of Afghan women judges spent their first night in rural Vermont, they were terrified. They had to sleep in rooms where they couldn’t lock the doors. “How can you not fear them?” they asked their American female hosts of their male colleagues. “They’re men!”

There are several such moments of cultural confusion in The Escape from Kabul, the remarkable story of a bond forged over years between women of a shared profession but very different societal pressures. In the wake of the Taliban takeover of Kabul in August 2021, an international group of female judges and lawyers felt they had an urgent responsibility to help their colleagues escape Afghanistan to safer places. “How very personal this was to all of us,” is how American judge Vanessa Ruiz put it.

After an astonishing reversal of two decades of foreign policy in Afghanistan enabled the Taliban to return to power, the global rescue effort of August 2021 – described as the biggest airlift since the Berlin blockade of 1948-49 – took more than 100,000 Afghans out of Kabul in a matter of weeks. Those days of panic and peril at the airport have been well chronicled since. This book tells, in detail, the remarkable story of one of many groups of Afghans who were left behind.

Author Karen Bartlett describes how a handful of women from New Zealand, Canada, the US and UK – members of the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) – sprang into action, even though they had no idea of what an evacuation would entail. This “sisterhood” felt the weight of responsibility, knowing many lives depended on their actions. Their efforts, Barlett writes, ended up taking “more than three years of late nights, endless Zoom calls, intense negotiations” long after Afghanistan had faded from the world’s headlines. “We very naively, as it turns out, thought that it would be obvious to anybody that these women should get seats on planes out of Afghanistan,” New Zealand supreme court justice Susan Glazebrook said.

But these hundreds of women judges weren’t on anyone’s list to leave, even though they had played a pivotal role in efforts to change Afghanistan, working in courts to confront deeply entrenched cultural norms, from violence against women and children to corruption and terrorism.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Related articles:

‘Do you recognise me?’ a man asked judge Raihana Attaee. Years earlier, she’d found him guilty of killing his wife

‘Do you recognise me?’ a man asked judge Raihana Attaee. Years earlier, she’d found him guilty of killing his wife

When Taliban fighters flung open the doors of prisons and detention centres on 15 August 2021, Afghan judges were in their sights, seeking revenge for rulings that had sent men into grim prison cells, or even sentenced them to death. “Do you recognise me?” a man demanded of Afghan judge Raihana Attaee when he rang her up. Years earlier, she’d found him guilty of killing his wife. “I found your number – and now I am going to find you.”

Attaee, among others, ended up being rescued by another female force of nature. Baroness Helena Kennedy, director of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute, raised millions of dollars to charter planes to transport more than 100 female judges, including Attaee, and their families to Greece and beyond. However, Bartlett’s decision to focus on the IAWJ’s work means compelling accounts such as these are glossed over. As a result of everyone’s efforts, more than 200 women judges have now been able to leave Afghanistan – but more remain trapped.

One of the greatest strengths of Bartlett’s book is in telling the stories of generations of Afghan women who fought to play a role in their country’s justice system – no matter who ruled Afghanistan.

Nafisa Kabuli was inspired to become a judge as a young girl, after seeing a policewoman patrolling her district. Having realised her dream, she came up against a chief judge who told her she must find a Taliban commander guilty even before she’d heard his case. “I always felt like my conscience was greater than my fear,” she said. Even during the years of international engagement, these judges faced what Bartlett summarises as “deep discrimination, corruption, and constant security threats”. And yet the country was supposed to be moving forwards.

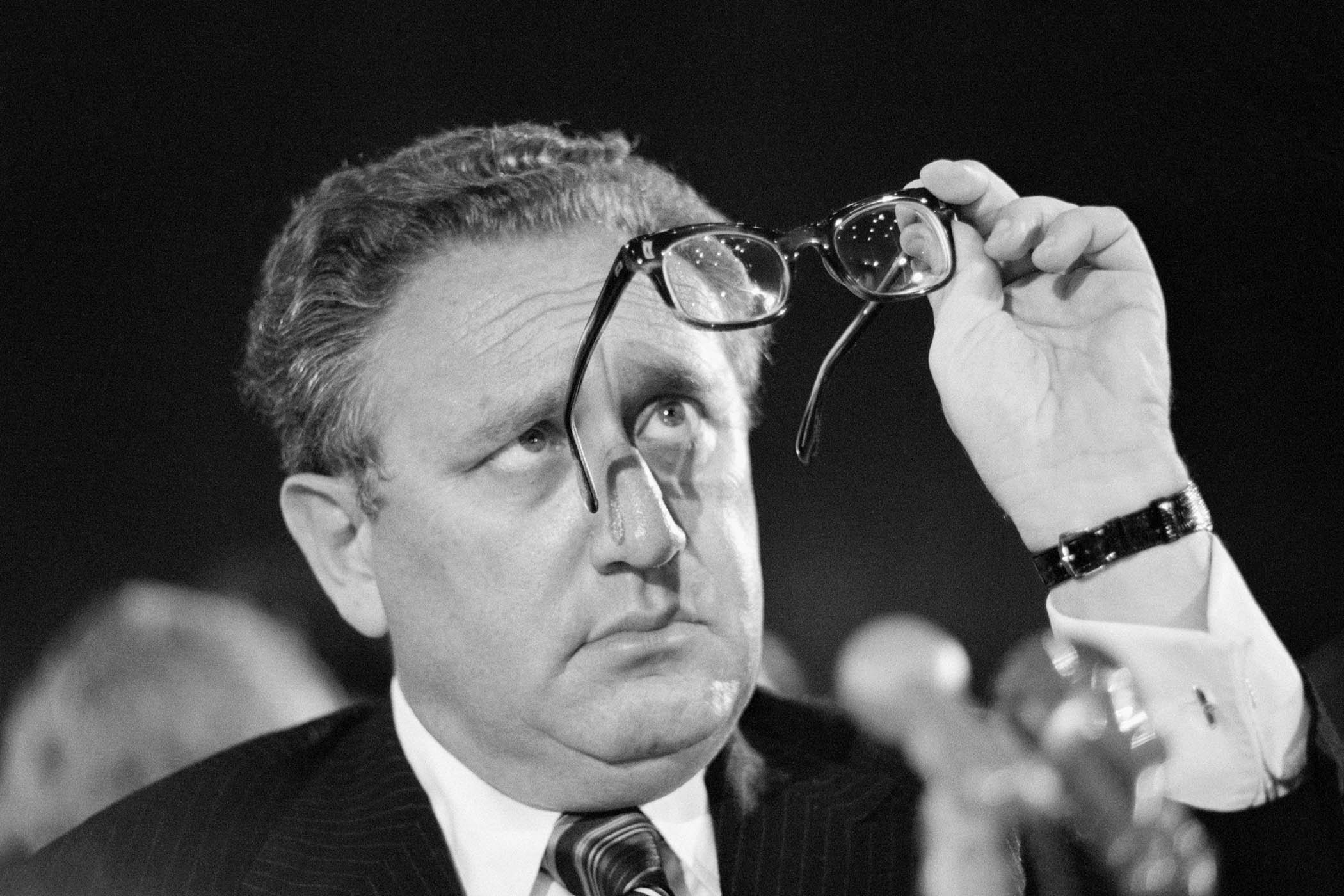

Above: Anisa Rasooli, ‘the Ruth Bader Ginsburg of Afghanistan’. Main picture: a family is airlifted out of Kabul, August 2021.

Anisa Rasooli, described as the “Ruth Bader Ginsburg of Afghanistan”, was the first woman to be nominated to the supreme court, in 2015, only for conservative clerics and male parliamentarians to reject her. Four years later she was nominated again. “The whole of parliament was willing to vote for me,” she told Bartlett, “because ideas about women were changing.”

The book reveals the challenges that face foreigners who involve themselves in the politics of other countries. American judge Patricia Whalen admits that, even though she had read books on Afghanistan and hosted Afghan women in Vermont, “after being there, I realised I knew nothing”.

Everything was upended when the Taliban returned to power, and despite promises to the contrary, their government has systematically removed girls from secondary education and women from universities and many kinds of work, including the courts.

The book also charts the painful but persistent efforts of women judges who, like many other Afghans now scattered the world over, found themselves starting new lives in new cultures. Raihana Attae expresses the yearning of many Afghans forced to flee: “As I left my country all I had was the hope that one day my colleagues and I could come back and start again.” That’s still a distant dream. But it’s one many Afghans hope for – and books like Bartlett’s help keep that hope alive.

The Escape from Kabul: A True Story of Sisterhood and Defiance by Karen Bartlett is publsihed by Duckworth (£12.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £11.69. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by US Air Forces Europe-Africa/Getty; The Washington Post/Getty