Sitting high on a plateau over Damascus, the imposing modernist white marble of Syria’s presidential palace is easily visible from the middle-class neighbourhood of beige high-rises where Ahmed al-Sharaa grew up. That the quiet, studious boy from Mezzeh, more often seen in the local mosque or his father’s grocery, is now living in the palace is remarkable to his childhood neighbours.

Mohammed Samy, the local barber who gave Sharaa the occasional haircut, recalls how people used to jokingly call the man who now rules Syria “Abu Ahmed” – Ahmed’s father. He seemed older than his adolescent years. Unlike his brothers, he wasn’t one to hang around with teenagers.

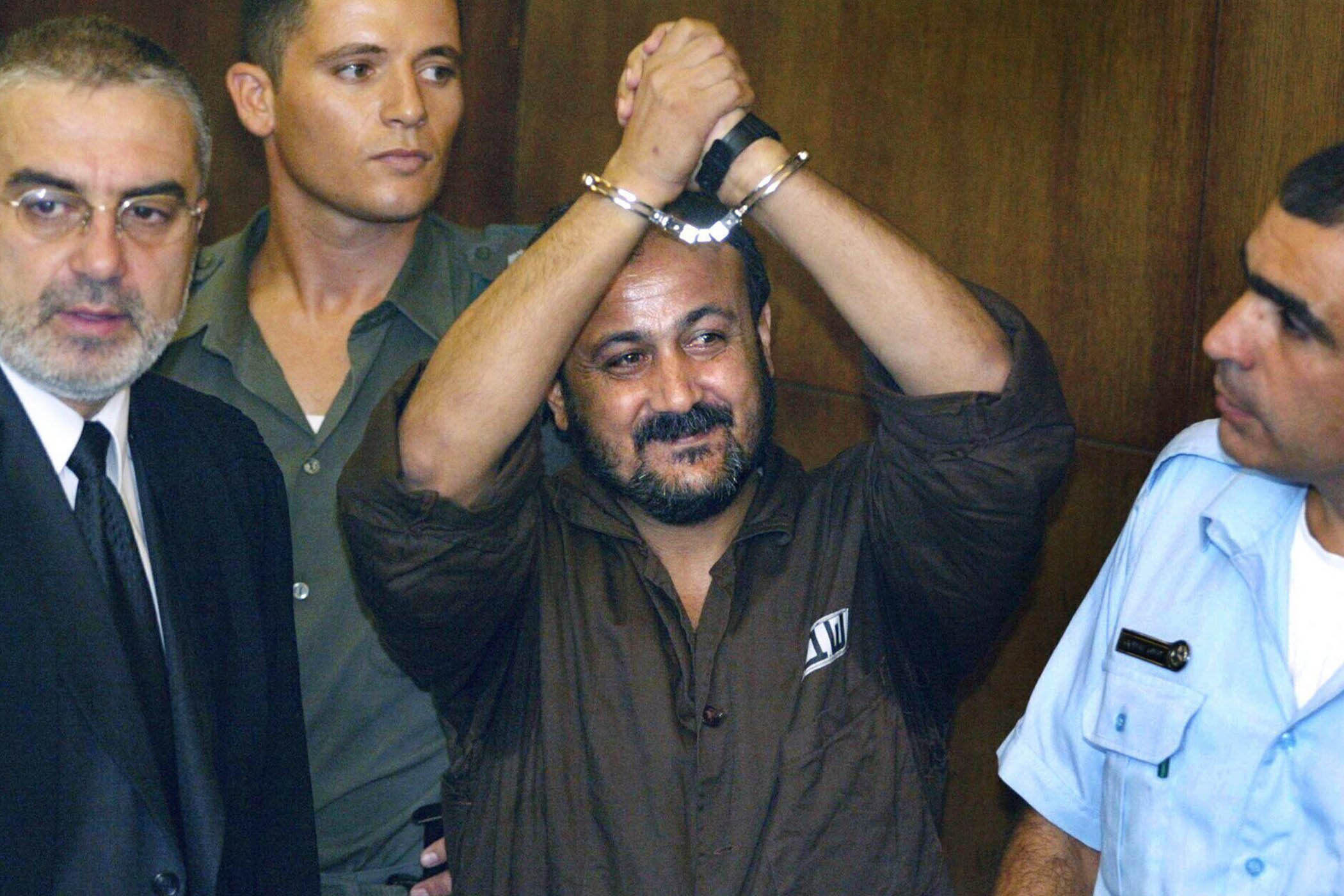

Sharaa spent his 20s in Iraq as a footsoldier for al-Qaida and his 30s in the rocky hills of Idlib leading a jihadist militia. Now he wears tailored suits and expensive watches and is described by his new ally, the US president Donald Trump, as a “young, attractive guy. Tough guy. Strong past.”

‘I told him you need to be as ambitious as Gamal Abdel Nasser’

Judge Ibrahim Khalil al-Hassoun

The question for Sharaa a year after the fall of Bashar al-Assad is what sort of leader will he be? Is he a careful operator who might be persuaded to heed growing demands from Syrian minorities and more secular revolutionaries to build an inclusive democracy? Will he rule like a warlord, as he did in Idlib? Or is he a new kind of autocrat, willing to rebuild and employ Assad’s security state, and to rule with an iron fist?

Becoming president

Related articles:

When The Observer met Sharaa in Idlib in 2023, he was dressed in a black zip-up fleece and scuffed trainers and was visibly uncomfortable being photographed. He did not look or act like who aspired to lead a nation – he was more focused on feeding the millions taking shelter in the city.

Last year, suddenly, everything changed: Sharaa spearheaded an insurgency that unexpectedly took the city of Aleppo and then headed south down a highway towards the capital. In less than two weeks the rebel leader arrived triumphantly in Damascus. Assad’s regime crumbled as the once powerful dictator fled to Moscow, leaving Sharaa and his allies to rebuild a nation crushed by decades of his corrupt and brutal leadership.

Two months later, Sharaa stood in front of an assembled room of fighters in camouflage fatigues who officially named him president. He has since ruled through presidential decree, with few signs of institutional checks on his power: Sharaa is due to appoint a third of the members of parliament, while a complicated ballot to select the remaining seats produced a result whose “most significant shortcomings”, according to a spokesperson from the elections committee, were a marked lack of representation for women and Christians.

Rebuilding a country from the ground up is no easy task, and Sharaa’s supporters claim he is the only one who can manage it. His detractors fear that by essentially appointing himself president seven weeks after Assad’s overthrow and concentrating more power around his office, he is abusing a groundswell of popularity to stoke fears that without him the state could crumble.

Those fears have been heightened by his reliance on a tight circle of allies whom he has vaulted from the rocky hills of Idlib into power in Damascus, as well as two of his brothers who now hold senior positions.

Judge Ibrahim Khalil al-Hassoun is one of Sharaa’s close advisers and something of an archetype: an adherent of the fundamentalist version of Islam known as Salafism, whose interest is in promoting a vision of religious governance rather than democracy.

The pair forged an unlikely relationship even after a faction of Jabhat al-Nusra tried to assassinate him – Sharaa later denounced them for joining Isis, which satisfied Hassoun, who is now the head of a top judicial authority within the new government.

Wearing a pressed checked shirt and Apple watch, Hassoun reflects on his path to the freshly renovated office where he sits at a grand desk under bright lights. He was put on trial by the Assad regime in the same justice ministry building where he now works and was sent to the infamous Sednaya prison in 2012.

His advice to Sharaa is focused less on democratic transformation and more on aping leaders with a cult of personality and an ability to remake the countries they led.

“You need to be strong,” Hassoun told Sharaa in one of their meetings. He advised Sharaa to imitate the leadership style of modern Saudi Arabia’s founding king, Ibn Saud, combined with that of the populist and charismatic former Egyptian military leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. The latter overthrew the Egyptian monarchy and inspired a generation of pan-Arab revolutionaries while also purging his enemies, nationalising the Suez Canal Company in defiance of western powers and weathering a military defeat by Israel.

“I told him ‘You read history very well’,” Hassoun said. “He really took that in. I told him ‘You need to be as ambitious as Gamal Abdel Nasser’,” he added, pointing to Nasser’s efforts to crush his political enemies, the Muslim Brotherhood.

A divided nation

The country that Sharaa now rules became more divided and sectarian during the 13-year civil war that followed the uprising against Assad.

In Sharaa’s first 12 months, two major instances of bloodshed have served only to inflame those divides, both of them involving accusations that his government’s security forces were either involved or allowed attacks to take place.

In the spring, a wave of violence targeting Syria’s Alawite minority killed more than 1,300 people on the Mediterranean coast, according to a monitoring group. Sharaa pledged that “no one will be above the law” if they harmed civilians – but months later clashes between Bedouin and Druze militias in the southern province of Suwayda left more than 1,000 civilians and militants dead, amid further accusations that government security forces had a hand in the attacks.

Fears grew that the new president may not have total control over the new army; that he was unwilling, or perhaps unable, to stop the violence.

Last month security forces in black fatigues had stood guard around Aleppo’s palace of justice and inside the courtroom to witness a first for the country: seven members of the Syrian security forces, along with seven Assad loyalists, on trial for their role in the bloody events on the coast. A second investigation into the violence in Suwayda recently saw the arrest of more security forces who were filmed committing attacks.

Members of the Alawite community now speak fearfully about a need to keep the peace among themselves rather than relying on the government. Abu Ali, a retired member of the powerful air force intelligence service who once guarded Assad’s home, has attempted to mediate between his community and the new authorities in the hope of calming tensions.

He pointed with concern to the killing of a Bedouin couple from a village near the city of Homs, where pictures quickly circulated showing sectarian messages scrawled on a wall in blood.

“It was about blood, a quick reaction,” he said. “That quick reaction caused displacement, violence and the burning of an Alawite neighbourhood in Homs.”

Yet as tensions rose in Homs and even in Damascus, the new government resorted to its failsafe: deploying more security on the streets of major cities, where uniformed men with assault rifles loitered near churches and at intersections.

Meanwhile, Israel continues to encroach on land far beyond the Golan Heights, which it has occupied for decades. Claiming to intervene in the name of Suwayda’s majority Druze population, Israeli forces have struck civilians and even bombed the defence ministry and presidential palace compound in Damascus earlier this year. The defence ministry building remains shuttered and still bears a gaping hole in its facade.

This has left Sharaa grappling with unresolved challenges on the battlefield and negotiating table. Large swathes of the country remain beyond his control and there are fears of a further Israeli advance. Months of talks to integrate the Kurdish forces who rule Syria’s northeast have faltered. Concerns about the persistence of Isis in Syria were exacerbated when the new government said it had foiled two Isis plots to assassinate Sharaa.

On the drive through the plains south of Damascus, the fragility of the security situation becomes clear. Checkpoints dot the dusty highways. Months after the violence in Suwayda began, Druze militias, increasingly hostile to Damascus, have gathered in force, and access remains limited.

Israeli troops have advanced deeper into the Damascus countryside amid fears of a land grab: 13 people in a remote village were killed recently in a raid, and drone attacks have become regular. Sharaa’s newfound allies in Washington remain desperate for an Israeli-Syrian security pact whose terms could prove wildly unpopular to the Syrian public.

Reclining on a plush red cushion as he pours tea, Hamza Fahed is enthusiastic about his new president. Describing a recent visit by Sharaa to Fahed’s home province of Daraa, south of Damascus, the young Bedouin activist and former fighter claims Syria’s new ruler is something that Assad could never be: a man of the people.

Fahed was optimistic about the situation in neighbouring Suwayda, which he claimed is slowly rebuilding ties to the rest of the country despite others living there describing a de facto government siege in recent months.

He was equally hopeful that the new government would continue to increase basic living standards, particularly in the farmlands dotted with olive trees in his part of rural Daraa, which now receives two hours of electricity at regular intervals – before, there was none.

He recounted a recent experience of being able to criticise the local security forces, which would have been impossible under Assad.

But in Fahed’s view there is one issue that could make him dislike the new president: concessions to Israel in any security agreement.

“If Sharaa does that, we will start a new revolution,” he said.

An ally of the west?

Those who have been close to Sharaa for years say his transformation from battle-hardened jihadist fighter to suited statesman was less sudden than it appeared. What emerges is a picture not of a fighter or ideologue but of a strategist: a leader who has long been capable of identifying threats to his authority – particularly other jihadist groups, including Isis – and either repelling or destroying them.

In office, he has become someone willing to build relationships with unlikely allies: the former member of al-Qaida who was once detained by the US government strode into the White House for a warm official visit in November.

A month earlier he had shaken hands with the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, in Moscow, the leader whose forces pummelled Aleppo and bombed Idlib so persistently that Sharaa launched the insurgency that ultimately toppled Putin’s ally, Assad.

Sharaa’s advisors, such as the imam Hasan al-Dughaim, insist that the new president’s ability to abandon old ideas and engage in realpolitik have been part of his charm for some time. Dughaim is jovial when we meet for coffee close to where Sharaa grew up in Mezzeh: he had spent the morning counselling members of Syria’s new army, and would later make the long drive home to Idlib. Before and during the uprising against Assad, he spent years attempting to combat the growth of jihadism in Syria.

Dughaim began writing to Sharaa in 2012 in a bid to pull Jabhat Al-Nusra and its fearsome group of fighters away from other radical jihadist groups. Over the next decade, Sharaa consolidated a swathe of Islamist armed groups in Idlib and rebranded them as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The group went on to set up governing institutions and provide services but was also accused by rights groups of detaining and torturing those who protested their rule. Feminist activists were closely watched and sometimes interrogated. Prisons in Idlib remain a black hole.

Even so, Sharaa’s political muscle, coupled with his willingness to fight Isis, impressed Dughaim, who said he was pleasantly surprised when the pair met for a meal in 2022 at a small hotel close to Idlib’s border crossing with Turkey.

Sharaa invited him to dinner to talk politics, namely how much the pair had in common: Dughaim, a former rebel spiritual leader and fighter, describes himself as a democrat. He was impressed by Sharaa, whom he described as widely read, particularly on matters of the economy. The rebel leader was also quick to spot pertinent reports in the British and American press and cite them in conversation. Dughaim started to believe that Sharaa had the power to lead a renewed rebel advance.

At a second dinner months later Sharaa denounced his former prejudices towards Syria’s Alawite minority. “He even asked me, ‘Surely you have some ideology you no longer believe in today?’” said Dughaim.

It was during this period, that Sharaa began to cultivate links with the outside world, even with powers he once battled. He met with the former US ambassador Robert Ford, while the previous head of MI6, Richard Moore, has said his agency “forged a relationship with HTS a year or two before they toppled Bashar al-Assad”.

In western capitals, Sharaa’s rise now presents a dilemma: they are required to back him for fear of Syria’s collapse, lack of a better alternative and his popularity on the ground. But if he fails to accommodate any of the more secular revolutionaries and civil society they backed during the uprising, or even cracks down on them, it is unclear if his government will listen to their criticism.

While Sharaa’s power has grown, many of the former revolutionaries who dreamed of a secular democratic Syria have been sidelined from the business of government. Some fear that Sharaa and his allies will overrule concerns about rights or claim the messiness of politics is unnecessary.

“Assad fell, but the revolutionaries didn’t win,” said a former judge who defected from Damascus early in the 2011 uprising. “The new government looks at the remnants of the former regime and the revolutionary types with the same eyes. They are forced to deal with those of us from the revolution during this transitional stage. But once they have total control, they will show us their true face.”

Photograph by Bakr Alkasem/Getty Images